Dr Rebecca Coates is Director of Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA)

Please download a copy of Of Greeks and Contemplation: The Antique and the Everyday here

OF GREEKS AND CONTEMPLATION : THE ANTIQUE AND THE EVERYDAY

a text by Rebecca Coates

There’s an exquisite little drawing that sits in the Queen’s Collection in Windsor Castle. As Andrew Hazewinkel researched Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of deluges and studies of water whilst based in Rome, he came across a reference to this small and little known 16th century drawing. 1 After circuitous introductions and lengthy correspondence, Hazewinkel had the opportunity to spend a brief couple of hours with the drawing in London.

It’s a tiny drawing, not even 12 cm square, and as all works in the Royal Collection are denoted, it is stamped in the bottom right-hand corner with the ER and crown. Possibly a political allegory, or allegory of Fortune 2, the work itself is done in ink, now faded to a dried-blood sepia tone. The drawing also bears the markings of other experiments in line, with dark charcoal-like smudging which may be part of the cloudburst drawing, or, as with so many of the drawings of this time, may be unrelated jottings made in haste on the nearest page to hand. There is text all over the page, both front and verso, in what appears to be Leonardo’s characteristic reverse mirror-writing in an old Italian dialect. O mjseria umana, ‘oh human misery’, spiders in reversed text across the base of the page: an ambiguity that leaves a contemporary viewer unsure whether this is a calamity we have bought upon ourselves. On a more prosaic note, the text on the rear appears to be six lines detailing Leonardo’s household expenses.

Leonardo’s drawing depicts a form of deluge, a cloud-burst of God-like proportion, where every-day objects appear to cascade from the sky. Though centuries old, the image has parallels to more recent footage of disasters from our natural world captured during the devastation of recent tsunamis and local floods, whilst the ominous cloud clusters appear not dissimilar to contemporary photographs of the great rolling cloudscapes of ash from the Icelandic volcano. 3 The scene has an extraordinary contemporaneity with many of the objects cascading from above indistinguishable from the detritus of our own modern times. They have a familiarity and an every-day quality of the stuff that clutters our 21st century lives. The rain of material possessions described in the catalogue includes ‘rakes, bills, bagpipes, barrels, clocks, ladders, pincers and spectacles.’ I make out forms that could be aerosol cans; a small plastic looking rake; rubber rings that tangle with hooks and the legs of upturned stools; and tubing, cylinders and dome-like forms, which in more contemporary times clog our landfill and litter our shores.

The seeming contemporaenity of the subject may have attracted Hazewinkel to this small drawing. For many years, and many European sojourns, he has captured footage of rivers in flood, gathered archival photographs of familiar locations made unfamiliar by the deluge, and documented the accidental installations and every-day accidents that appear as the water recedes. Whilst the specific locations are less important than the flotsam and jetsam that eddies and swirls or the patterning and marking that appear in the mud, I cannot help be fascinated by familiar locations made unfamiliar by extraordinary events. Rome’s Pantheon half-submerged in the Tiber’s excess; or furniture floating by as rivers burst their banks – the domestic made unfamiliar through its watery change. There is a stillness to these photographs, and silence from the absence of people and human form, which is belied by the raging fury of the video footage however much it is slowed down. Nature unleashed has the ability to make even the most ubiquitous item of 21st living, the plastic bag, an object of beauty and – albeit ambiguous – wonder.

The archaeology of the lost and found

It is quite possible that Hazewinkel’s Acqua Alta series of works also enjoins the viewer to reappraise particular buildings and architectural spaces. He seems to draw attention equally to the buildings that house the project as the project framed within the walls. In this, I am reminded of one of the 20th century’s seminal installation works, Marcel Duchamp’s Sixteen Miles of String, 1942. Though more like one mile in length than the intended sixteen, Duchamp famously hung several hundred feet of twine in and around work in the first international Surrealist exhibition in the United States. Titled the First Papers of Surrealism, the exhibition was held in midtown Manhattan’s Whitelaw Reid mansion. Acting in part as a veil, Duchamp’s white string not only masked part of the Gilded Age architecture of the Mansion and some of the paintings displayed in the exhibition, but also operated as a device to draw visitors’ attention not only to the ‘art’ itself but also to the physical experience of the exhibition space.

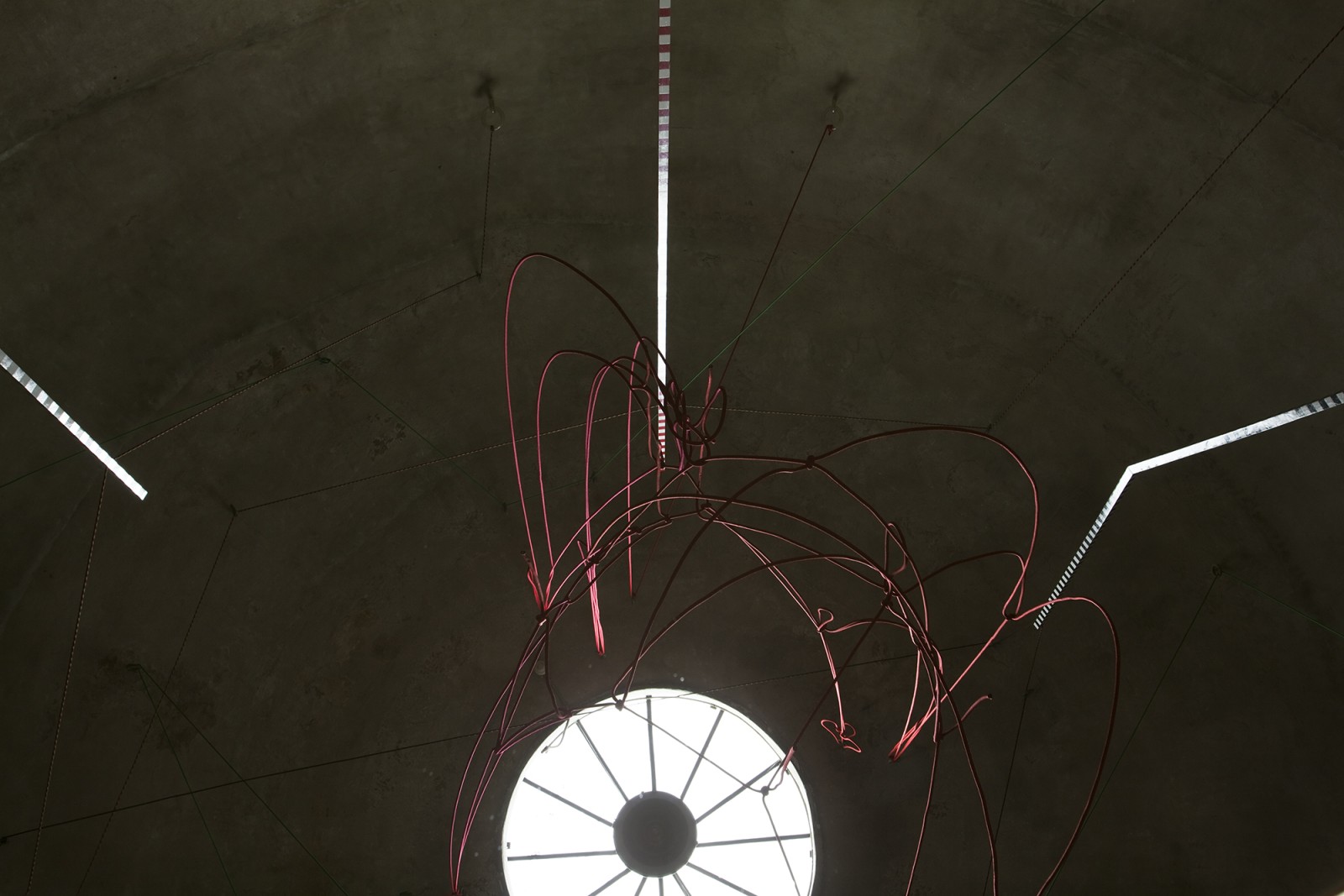

Where Hazewinkel’s previous Acqua Alta projects may have used rope like Duchamp’s string, Acqua Alta #4 pushes beyond a device of veiling and relief. Though Hazewinkel’s delicate tracery of spider-like webbings formed by coloured climbers’ rope loop through architectural details, objects, and fixed points in space, within the centre of the tautly delineated space is an organic tangle of red. Looping and twisting, the marine rope has an organicism, both of material and form, more akin to Eva Hesse’s minimalist explorations than its surrounding frame.

The Acqua Alta project has continued to develop and evolve through time, creating a series of works that also link through time, commencing in Rome and now concluding in one of Melbourne’s often overlooked architectural gems. Acqua Alta #4 is presented in the former gymnasium building of the Seamen’s Mission. Designed in 1916 by architect Walter Richmond Butler, the Mission to Seafarers building was intended to reflect Melbourne’s significance as a centre for shipping commerce. With the changing tides of the city’s focus and locus of economic wealth, this once grand building now sits rather forlornly, like a footnote in time, dwarfed by the adjoining Melbourne Convention Centre on a busy axial thoroughfare to the burgeoning Docklands and Melbourne’s west. The building’s exterior is a pattenated concrete and brick confection of Spanish Mission Style and English Arts and Crafts, framed at one end by the Chapel, and the other by a gloriously proportioned domed space lit from an overhead oculus window. Far smaller in scale and more modest in form, the cement dome and oculus shape cannot but remind viewers of its Roman exemplar, the Pantheon, and the many subsequent architectural monuments it has inspired.

There is a love of architecture in Hazewinkel’s choice of building, as well as an ongoing attachment to the buildings and history of Italy and Rome: from the Neo-Classical columned façade of the British School where the project was first presented, through the rather muddled Melbourne stucco of the Italian Cultural Institute, to the pared back aesthetic of timber and pressed metal ceilings in the 1930s Art Deco Elwood mansion apartment.

Into this framework, Hazewinkel introduces his installation-based work created from coloured ropes reminiscent of Duchamp’s string, and a system of cast fiberglass eyelets, or fixing rings, that he has employed for each of the various project’s installations (the source of inspiration for these objects a piece of metalwork embedded in the stone wall of the Tiber, for mooring boats). There is a sparseness to this web of coloured rope, that while referencing volumetric shape and recent histories of institutional critique, also has psychological overtones of containment and control. Objects are variously inserted, and caught in the web: a wicker chair hung suspended and upside down in Rome; a red plastic framed circular mirror; the discarded frame of an unusable deck chair; video footage from the river in flood, and a series of photographs (some historic whilst others recent) of Italian cities in flood juxtaposed with the artworld-like sparseness of the homeless living in temporary structures along the banks of the river. Hazewinkel’s use of every-day objects certainly continues numerous contemporary artists’ interest in and incorporation of the often-ignored objects of today’s world as an expression of their desire to invite interaction between the artwork and the audience. What extends it is his inclusion of a series of forms that both reference minimalist sculpture in their shape and intent, whilst also referencing the nautical underpinnings of these projects - red for port and green for starboard.

Mirrors

Along with his series of found and reconfigured objects, Hazewinkel’s use of mirror and mirrored surfaces in Acqua Alta#3 links him to a long trajectory of artists in Western art history who have experimented with the reflected gaze. Mirror, as Ann Stephen suggests, is the ‘surface par excellence of late modernism. Its paradoxes confound the illusion of transparency – indexing the instabilities of perception, while offering the possibility of reflexivity.’ 4 The conceptual artist Ian Burn writing in the late 60s reflected that ‘a mirror produces not only an event or a piece of self-conscious theatre, but also deflects visual attention away from the object itself.’ 5 Similarly, the small red-framed cheap plastic mirror that Hazewinkel first employed in project #3 acted like a reflective oculus, or 16th century convex mirror: a device that not only echoes space, pinpointing specific spatial interrelations, but also acts as another element in the creation of spatial illusion.

The reflective sump oil in Acqua Alta#4 works on a different level. It mirrors and reflects, but also absorbs in a way that the silvery surface of glass and paint doesn’t. As with the string, or ropes festooned in architectural space, the sight – or smell – of this viscous substance has antecedents, particularly British installation artist Richard Wilson’s piece 20:50, first installed at Matt’s Gallery, London in 1987, and then permanently located in the North London Saatchi Gallery in 1991. Dealing with volume, illusionary spaces, and auditory perception, as visitors were invited to walk out into the lake of oil without visible lip or edge (through the use of a hidden walkway almost completely submerged in the oil), the reflected surface created an illusion of the room turned upside down and inverted. Hazewinkel’s smaller, and more discreet pool of oil, placed in the centre of the domed space, creates a similar illusion of space as it reflects the oculus and domed ceiling from below. Unlike Wilson, Hazewinkel does not fill the oil to the rim. Rather than a pool of infinity, Hazewinkel has created a viscous mirror – Narcissus in a toxic pool – a further device to reflect entanglements and light.

To end

I began with an element of the exhibition that does not appear: Leonardo da Vinci’s small work on paper. It has become a refrain, this small and powerful motif, rather like the soundscape that quietly permeates Acqua Alta#4. Although our lack of knowledge of Leonardo’s work does not lessen our experience of Acqua Alta#4 in its architectural context, our knowledge and understanding of it through the exhibition catalogue makes this experience all the richer. It is another layer in this textured installation of objects and sound.

As the Acqua Alta project has evolved, it has been pared back, objects significant to place have been added, and spatial considerations have evolved in response to site and time. Sump oil has appeared, presented in a shallow metal disk whose form perfectly replicates the oculus window above. Fabulous hydrometer-like forms hang pendulously from the dome, striated variously in red and white stripes, silver and black, echoing devices used to measure the relative density of liquids. A projection of billowing plastic and bunting in the wind captured and slowed echoes canvas rigging, or the inexorable pull of the ocean tide. The accompanying soundscape becomes an aural landscape of sonar blips and man-made tides. Through mirroring and reflective surface, light is replicated, projected, and captured through line, each echoing surface acting not simply as a looking-glass or readymade. Each of these discreet forms, suspended to inhabit the space, are linked by the series of lines and voids. Though some lines are taut and some are at ease, the whole – with its precision and consideration of space and form – invites us to consider carefully this moment in time.

1. The work appears as catalogue entry 12698 in Clark, Kenneth. The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Revised with the Assistance of Carlo Pedretti. Vol 1, 2nd Edition, London: Phaidon, 1968, p. 176.

2. Ibid.

3. Iceland’s Eyjafjallajokull glacier erupted on 14 April 2010, closing international airports and causing air flights to be cancelled for a matter of weeks.

4. Ann Stephen, Mirror Mirror then and now, ex. cat., IMA, Brisbane, 2010, p. 5.

5. Ian Burn, ‘Glimpses: On Peripheral Vision’, in Dialogue: writings in Art History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991, p. 191 cited in Stephen.