MS

UNBOUND OBJECTS:

NOTES ON THE EXHIBITION THEORIMATA 2 / ON HISTORY

2020

An illustrated PDF of the text is available here

The word ‘Ιστορία ̓ (Historia, history) derives from the verb ‘οἶδα’ (oida, to know) while the noun ‘ἵστωρ’ (histor) means connoisseur, eyewitness, judge 1

Sometimes, not often, I return more than once to a temporary exhibition. There is something in the ephemerality of their staging that usually makes me move on. Theorimata 2: On History organised by AICA Hellas (the Greek chapter of the International Association of Art Critics), presented at EMST (the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens), was one of those rare occasions when I looked forward to going back. Perhaps that was because the idea of return (or better – recurrence) used here within the context of history, was central to the exhibition’s conceptual theme and inescapable throughout.

The idea that knowledge of the past can be deployed as a tool for interpreting the present, and function as a future-shaping force, as mentioned in Thucydides’ first book of the Peloponnesian War, was palpable everywhere. At varying degrees it resonated from within, and dialogically between, the works of 56 contemporary Greek artists selected by 25 curators in response to the project’s overarching curatorial prompt - On History - offered by Bia Papadopoulou art historian, curator and General Secretary of AICA Hellas.

The exhibition was conceptually and physically expansive. After descending the escalator to Lower Level 1 and entering the main exhibition space (a post-industrial chamber offering residual presences of the building’s past lives alongside contemporary opportunities), two programmes of transition were offered. You could choose your own entry and exit points of the main body of the exhibition.

I visited twice. The first time, unconsciously, I moved through the space in a clockwise direction. The circuit took me about 2 hours. Days later while planning my second visit I took the conscious decision to move through the exhibition in an anticlockwise direction so as to not prioritise either directional flow and to uncover new connections between the works. Moving in an anticlockwise direction was a simple performative strategy designed to neutralise the idea of singularly progressive linear time and thereby its slow-dance partner, singularly progressive linear history.

I have purposefully allowed a few weeks of contemporary Athenian history to wash around us before sitting down to write this response to some of the works in On History. During these passing weeks we have re-entered (for the second time) a national Covid-19 related lockdown. Schools, universities, cinemas, theatres, museums, galleries, libraries, bars, tavernas, archaeological sites, and shops are closed. Only medical facilities, pharmacies and supermarkets remain open. A nightly curfew is in place between 9pm and 5am. To leave home during daylight hours we are required to send a SMS to the government health authority providing our names, addresses and the numeric that denotes one of six permissible reasons for leaving home. Social and economic distress is tangible. It hangs in the air. The collective narrative is littered with intimate micro-histories shaped by anxiety and fear. They are palpable. All of this is unfolding in an atmosphere of increasing geo-political tension (with our neighbours to the East) as the flows of people seeking safety, refuge, asylum, as well as opportunities and the imagined future histories they might bring, are pushed back.

Perhaps perversely I find myself hoping that the EMST de-installation crew did not have time to demount the exhibition before the stay at home rule came into effect, and that as I write the entire On History project remains suspended in the uncertain atmosphere of our immediate history as a kind of cell-like history-capsule hovering above the reduced traffic flow on the arterial Leof. Andrea Syngrou.

I wish that I could go back to the exhibition a third and fourth time with the belief and trust that the artworks in the exhibition would help me to make some sense of the difficult passage that we, along with the rest of humanity, are moving through. And that is because at the end of the day, minor histories and grand historical narratives are shaped by individual and collective experiences that are inscribed as much on our skin and in our hearts as upon the monuments that surround us.

Transcriptions (2019) by Efi Fouriki, selected for On History by Athena Schina, engages with the exhibition’s theme through a series of ramifying art historical, science historical, philosophical, and for me, personal associations.

Comprising a large, black and white digital photographic reproduction of Johannes Vermeer’s painting The milkmaid (c.1660), Transcriptions also includes a looping, localised, largely monochromatic, video projection with natural sound. The assembly was supported from behind on a pragmatic timber framework and was presented standing on the floor. Fouriki’s formal presentation strategy mingled histories of the picture plane and figurative sculpture.

Scale is important aspect of Transcriptions though it might easily be overlooked in reproductions of the work. The pictorial referent of Transcriptions, (Vermeer’s The milkmaid) is modestly scaled at 45.5 x 41 cm. Fouiki’s digitally enlarged, cropped and chromatically desaturated version is (according to the artist’s website) 194 x 127 cm. which approximates the size of a door - I will come back to that.

The strategic shift in scale means that the young woman, who in Vermeer’s original we are invited to gaze upon, is represented in Fouriki’s work at roughly one to one human scale. Fouriki’s milkmaid stands before us as she goes about her daily work; we share a common ground. She establishes and greets us at a threshold of temporalities which we sense with our body and in our mind. Fouriki’s combined shift in scale and presentation strategy uncovers a threshold between at least two temporalities which Transcriptions gently urges us to cross in rhythmic oscillation.

The understanding that an artwork can heighten our sensibilities to the fact that we inhabit a multiverse of temporalities is taken up by the Postclassicisms Collective (albeit in relation to engaging with the field of Classics, but also of relevance to On History’s conceptual framework), when they state ‘No one is ever simply “in” a time and place: one is always inhabited by several different times and places – historical, experiential, biological or cosmological – that are as determinative of one’s identity as they are outside one’s ultimate control.2

I grew up in outer suburban Melbourne in what was at that time a fishing village. Both of my parents were/are Dutch. They had come to Australia as part of the diaspora of young people seeking new opportunities having grown up under German occupation during WW2. They sought to write new future histories for themselves and we, their children, in the turbulent wake of their own childhood experiences. As is often the case with migrant families, we moved house a number of times and a reproduction of Vermeer’s milkmaid moved with us. She was always with us, hanging around in various rooms. I never paid her much attention, no one seemed to, but she was always there. My enduring memory of her presence in our family home is one of luminous modesty and a strange umbilical quality connecting me to longer, deeper histories- familial, geographical and cultural.

With Transcriptions Fouriki intervenes into manifold histories (including art histories) by making one simple remarkable move. She deploys a pictorially localised moving image that replaces the static milk in Vermeer’s original with an endlessly looping video of the milk flowing from the jug in the maid’s hands into another vessel which is resting on the table. Here milk, with oblique reference to the maternal, pours in perpetuity.

With the aid of chaos theory and fluid-state physics, philosopher and historian of science Michel Serres (1930-2019) re-examines the atomist thinking presented by Lucretius in his poem On The Nature Of Things - (De Rerum Natura). Serres’ reconsideration of Lucretius’ ideas can be found in his book The Birth Of Physics (1978) in which he develops a fundamentally nonlinear conception of history which he calls ‘liquid history’. In Serres’ conception we live in time composed of manifold temporalities characterised by individuating flows (of different speeds) and topographical surfaces.3 As the Postclassicisms Collective have pointed out Serres’ liquid history requires both recurrence and difference, and that it is these two qualities together that distinguish his conceptualisation of time from linear historicism and timelessness.

It is the continuous rupture created by the endlessly flowing milk in Fouriki’s Transcriptions that imbues her work with a sense of recurrence and difference.

Standing with the work I became mesmerised by the sound of pouring milk, entranced by its motion, everything slowed down, I became hypnotised and imagined a single stilled drop of falling milk as a pearl, which transported me to another history manifest in the form of another painting by Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665).

Mentally conjuring an image of Girl with a Pearl Earring it would be easy to mistake the painting as a portrait (a genre with powerful allusions to privilege), however it is not a portrait. Girl with a Pearl Earring is a ‘tronie’, which is a specific genre that emerged from 17th century Dutch painting’s interest in scenes of everyday life (as exampled by Vermeer’s The milkmaid). A tronie does not represent an individual person in the same way that a portrait does, rather it represents an imagined ‘type’ of character, it describes one aspect of a broader collective social narrative, and in this way might be considered closer to the genre of history painting than portraiture.

Transcriptions does many things, not least of which is that it unleashes the predicament of temporal identity, it offers an explosive encounter between two different, typically discrepant and hence impure temporalities, which is the condition of being untimely.4 Here histories are not recorded in stone, rather in a nourishing liquid, flowing milk.

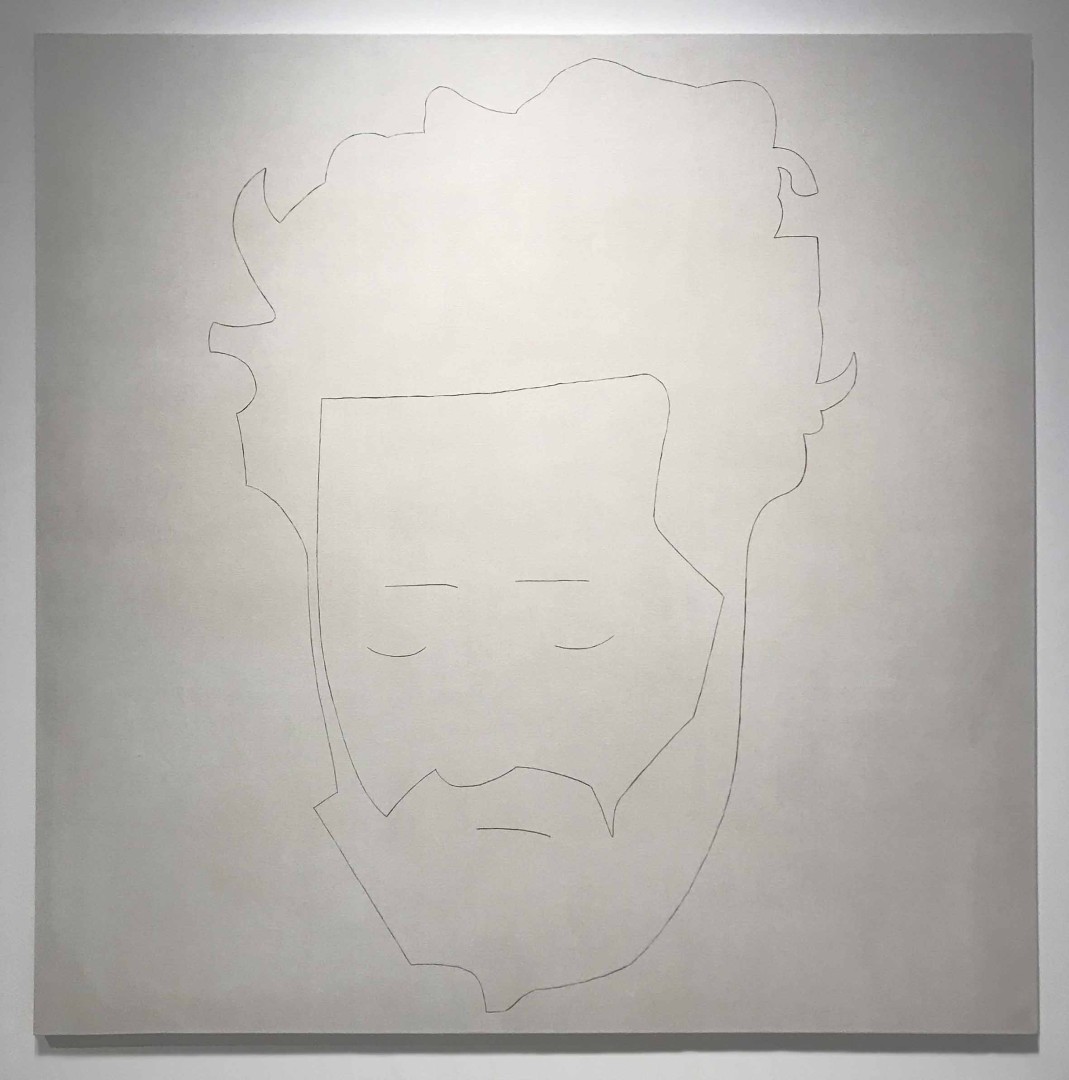

Ilias Papailiakis’ painting The head of Velouchiotis (2020), selected for On History by Lina Tsikouta, brings to mind Henri Bergson’s memory related assertion that the body is an ever-advancing boundary between the future and the past.5

There are two reasons for this. The first reason is that although the painting represents, in exquisitely restrained linearity, a disembodied head, awareness of the artist’s inspiration for making the painting implicates the viewer, or more specifically the viewer’s body.

Papailiakis found inspiration in a photograph of a dead man (Velouchiotis). When faced with death the body is never (perceptually) far away. Here the absent body of the Velouchiotis mingles with the viewer’s tacit sensibility of their own body. Thinking about the painting in this way makes it as much about our own corporeal futures as it is about Velouchiotis’ past. Here history is intimately embodied.

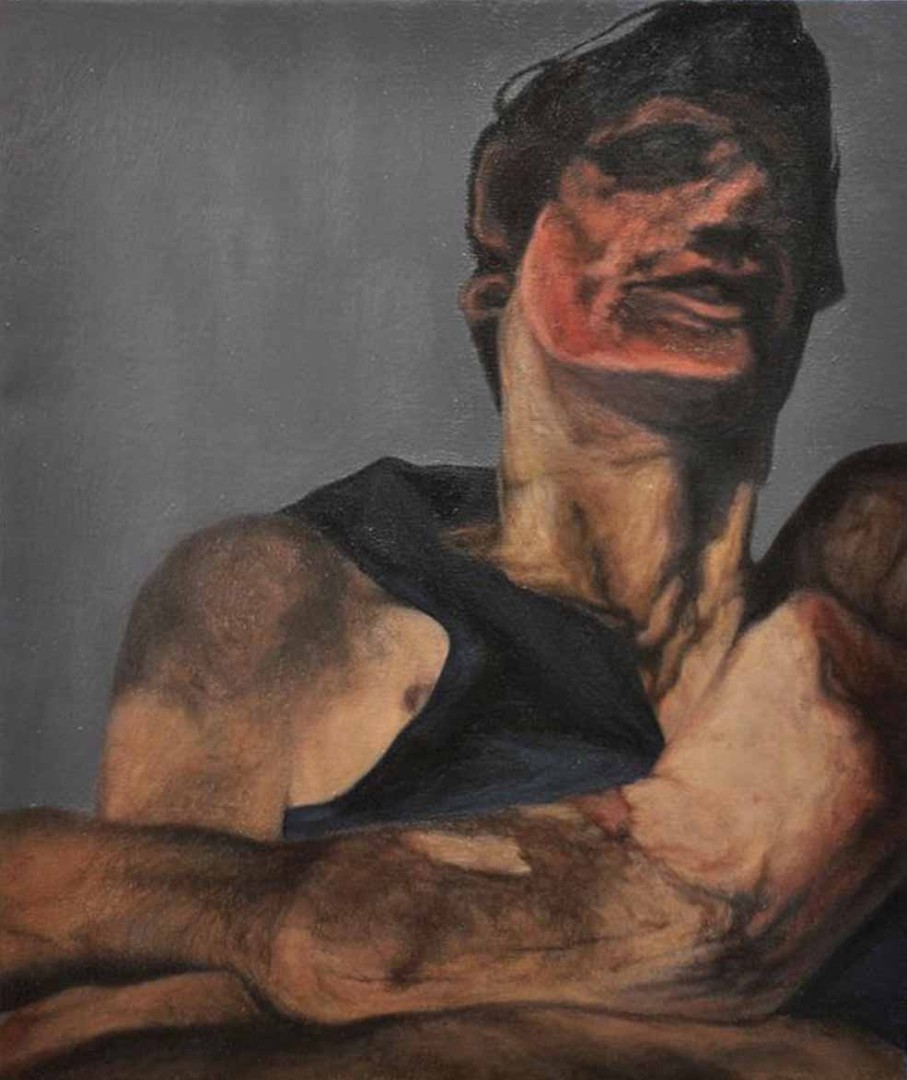

The second, perhaps more abstract reason, is caught up with my earlier encounter with another painting by Papailiakis. The portrait of P.P. Pasolini (2015) which hangs on a wall two floors above On History where it is included in the current iteration of the EMST Permanent Collection show.

Although outside the main corpus of On History, this much smaller, bloody, bruised, visceral portrait of Pasolini (which bears no stylistic resemblance to The head of Velouchiotis) is for me part of what we might call the expanded field of On History, which stimulates and is stimulated by our individual histories.

This is especially relevant when we consider that for the great poet cineaste provocateur P.P. Pasolini history was not recorded in stone, rather released through something more easily overlooked, fleeting gestures, like colloquial speech or the rhythms of dialects passed from generation to generation. Those somethings he called lucciole (fireflies) bright flickering visions that dart in and out of perception.6 Contemporary art historian Anthony Gardner has pointed out ‘To glimpse these lucciole means being open to engaging with history as something lived, not simply read, and being sensitive to historical recurrence in unexpected and even ungraspable ways.’7

Pasolini’s perspective on the transmission of history was taken up by historian George Didi- Huberman who explains that lucciole, or ‘minor’ histories, can easily evade capture within the dominant understandings of the past and can be considered forces of resistance that open up new perspectives of history.8

In the On History exhibition catalogue, Tsikouta reminds us that Papailiakis has a history of taking historical figures as subjects - Nikos Zachariadis and Aris Velouchiotis are good examples. For readers less familiar with 20th century Greek military and political events and structures (if at all separable), Nikos Zachariadis was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Greece between 1931-1956 and is said by some to be one of the most significant personalities in the Greek Civil War. Aris Velouchiotis, the nom de guerre of Athanasios Klaras (1905 -1945), was the most prominent leader of the Greek People’s Liberation Army, the military arm of the National Liberation Front, which was the major resistance organisation in occupied Greece between 1942 and 1945.

The cool restrained minimalist aesthetic that Papailiakis employs in The head of Velouchiotis (and much of his recent work) is comprised of set of precise curving lines set against a tonally subtle (almost monochromatic) field. It quietly and purposefully unfolds a tension that creeps up on the viewer. It is a bit like the paradoxical sense of tranquillity that can be found in the plaster death masks of executed 19th century individuals found guilty (often wrongly) of crime. The elegant qualities of the seven lines that comprise this sombre, solemn, even mournful composition somehow highlight the unseen (but understood) bloodiness and horrors of war. I don’t respond to Papailiakis’ handling of his subject as an aesthetic or cosmetic glossing of history, rather I see it as studied restraint. This way of working with violent histories finds accord with Slavoj Žižek’s premise that thinking about and engaging with violence in a less directly confrontational manner lessens the seductive yet blinding effect of direct confrontation.9 Here we see no gore, no blood, no bruising, just the tranquil stillness of death.

This year marks the 2500th anniversary of the Battles of Salamis and Marathon. Greece is marking these defining military victories with all manner of celebrative commemorations. A painting by Konstantinos Volanakis, The Naval Battle of Salamis (1882) hangs in Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ office at the Maximos Mansion,10 and the National Archaeological Museum Athens is presenting the exhibition The Great Victories: On the Boundary of Myth and History.

2021 is another important commemorative year for Greece in that it marks the commencement of the Greek War of Independence, but 2022 represents another military anniversary for Greece, one less easy to celebrate, rather it represents a profound wounding, the nationally defining 1922 loss to Turkish forces that resulted in devastating internal convulsion.

Just as the scars on our bodies remain testament to injurious histories, they also testify to the process of healing. Perhaps considering The head of Velouchiotis as a history painting rather than a portrait of a dead man allows it to function, for contemporary Greek culture, in the much same way, describing a profound loss, a searing wound and its healing.

In the early pages of her book Liquid Antiquity classicist Brooke Holmes writes ‘To enter instead the imaginative space of what Michel Serres has christened ‘liquid history’ is to engage nonlinear models of time such as fold, anachrony, and seriality, models informed by the turbulent logic of rivers and seas and the capacity of water to make connections across vast distances.’11

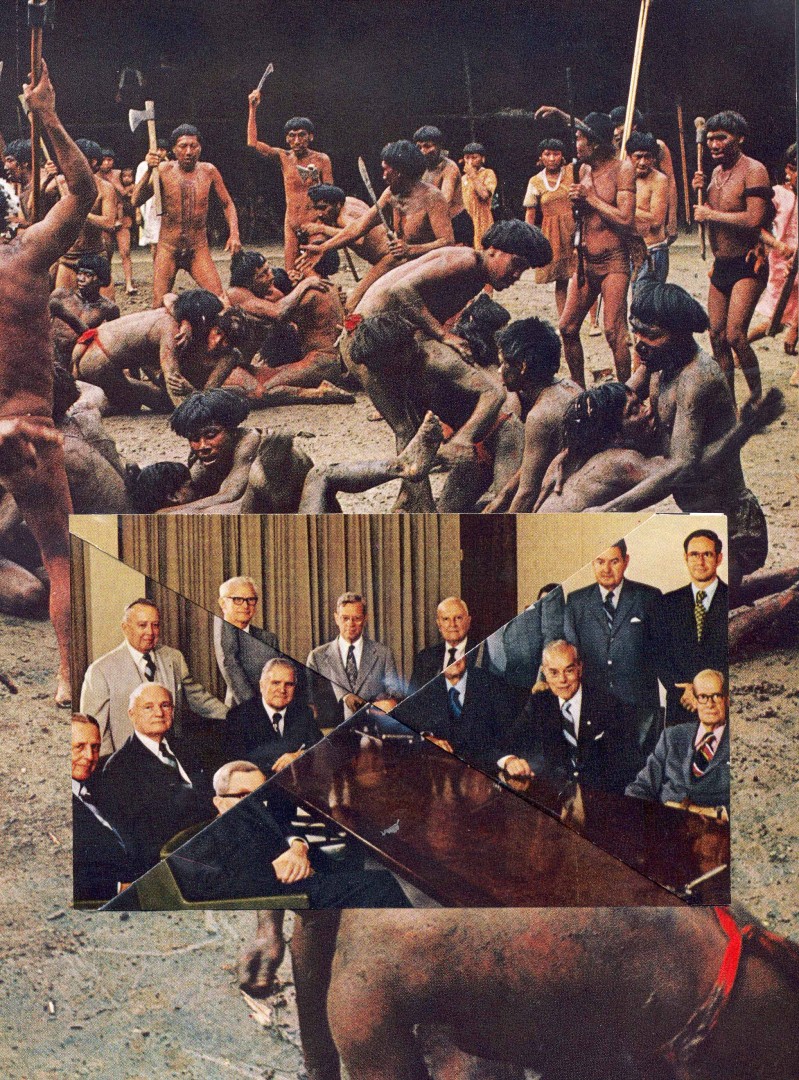

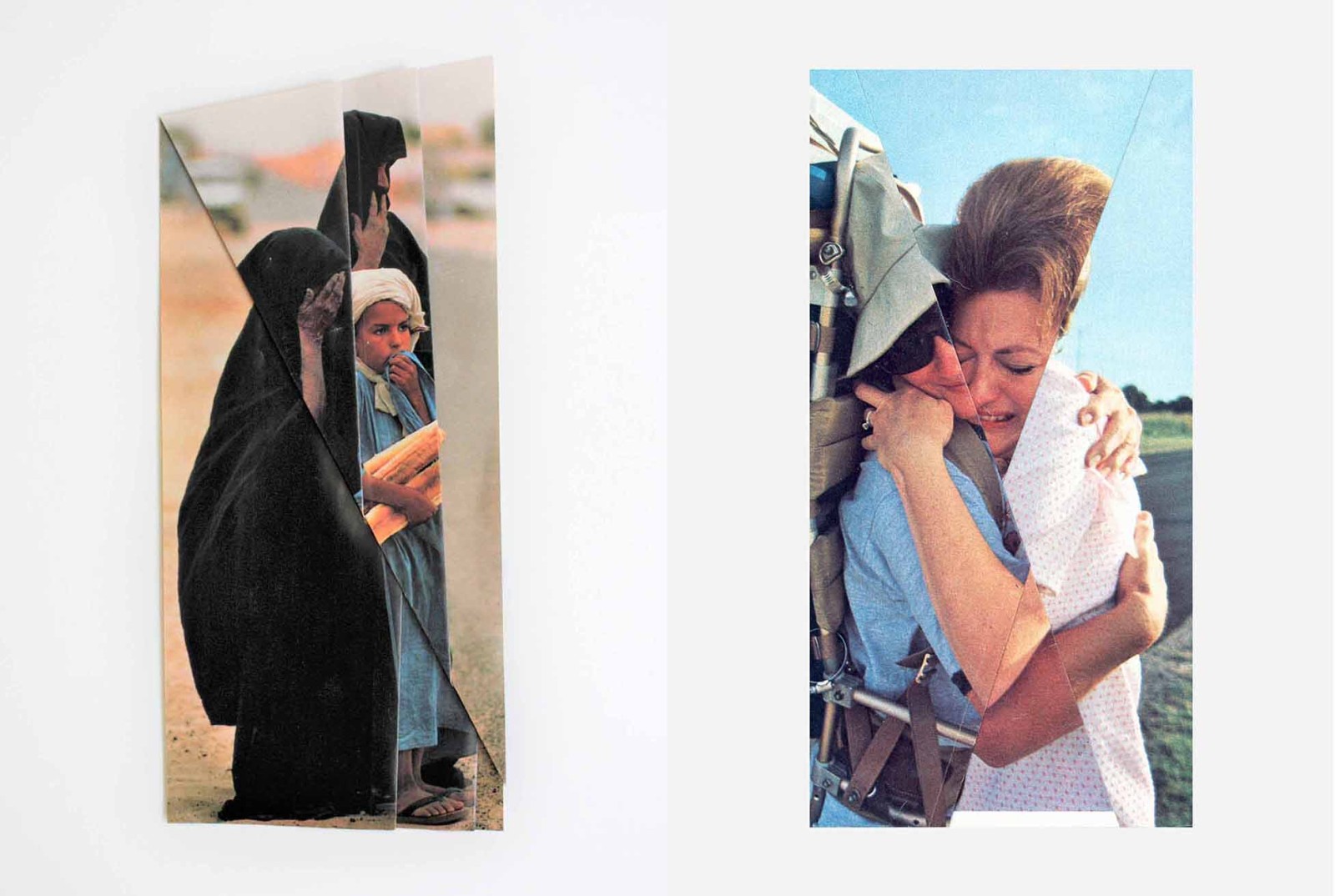

The fold, anachrony and seriality characterise the work of Giorgos Tserionis selected for On History by Bia Papadopoulou. The ensemble of 20 works on paper (or better - with paper) drawn from the Tserionis’ ongoing series Mature Topography (which began in 2009) were chosen through close collaboration between the artist and curator. For On History, Mature Topography (2018) was arranged in four thematic friezes presented in a grid formation. In the exhibition catalogue Papadopoulou describes the ensemble as a ‘complex artistic puzzle to be read cinematographically, inviting the viewers to wander into a world divided into the powerful and powerless, into victimizers and victims.’12

Deploying a strategy of folding, Tserionis enacts Serres’ best-known model of nonlinear time, which is fundamental to his conception of liquid history. Explaining his model Serres lays flat a handkerchief and then draws a circle on it. This makes obvious that some points are further from others along the arc, and that some are closer. He then picks up the handkerchief and crumples it demonstrating another set of proximities. This is precisely what Tserionis does, but he takes Serres’ model one step further by putting the now crumpled handkerchief in his pocket and inviting us for a walk in the world.

Tserionis works with found images, old National Geographic magazines to be precise, which he sources from the great reservoirs of undocumented personal histories - flea markets and second hand bookshops. As Papadopoulou insightfully reaffirms, the images comprising Tserionis’ source material immortalise stories of dominance and submission throughout the world. The artist describes his attraction to them when he explains ‘I am interested in pictures that are motivated by my personal involvement in sociological and political situations.’

With these seductively shocking images Tserionis engages the centuries old Japanese practice of origami. In doing so he reveals new perspectives, new questions, new meanings, new realities. While the act of folding is formal, what it reveals is soulful.

The first of the four friezes folds together images of suited directors of multinational companies with images of the indigenous people of the Amazon rainforest, offering us a commentary on white supremacy and colonial attitudes and behaviours.

In frieze 2, folded images of burka-wearing women seeking aid in the desert, and images of other immigrants and refugees, are contextualised by the work of another artist, Doris Salcedo, specifically her work Shibboleth (2007) which took the form of a crack in the glistening polished concrete floor of the Tate Modern’s vast Turbine Hall. This frieze brings into strikingly entangled visibility, loss, trauma, border politics, displacement, privilege and poverty.

Frieze 3 focuses on human touch, prioritising that part of our body most touched by strangers - our hands. Here prayer, dirge, emotional pain, embrace and solidarity unfold. Papadopoulou describes the hands in Tserionis’ work as symbolic extensions of the soul. Hands are present in four of the five works in this frieze; the only image in which they do not appear is a parody of a kiss between the late 20th century world leaders Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin.

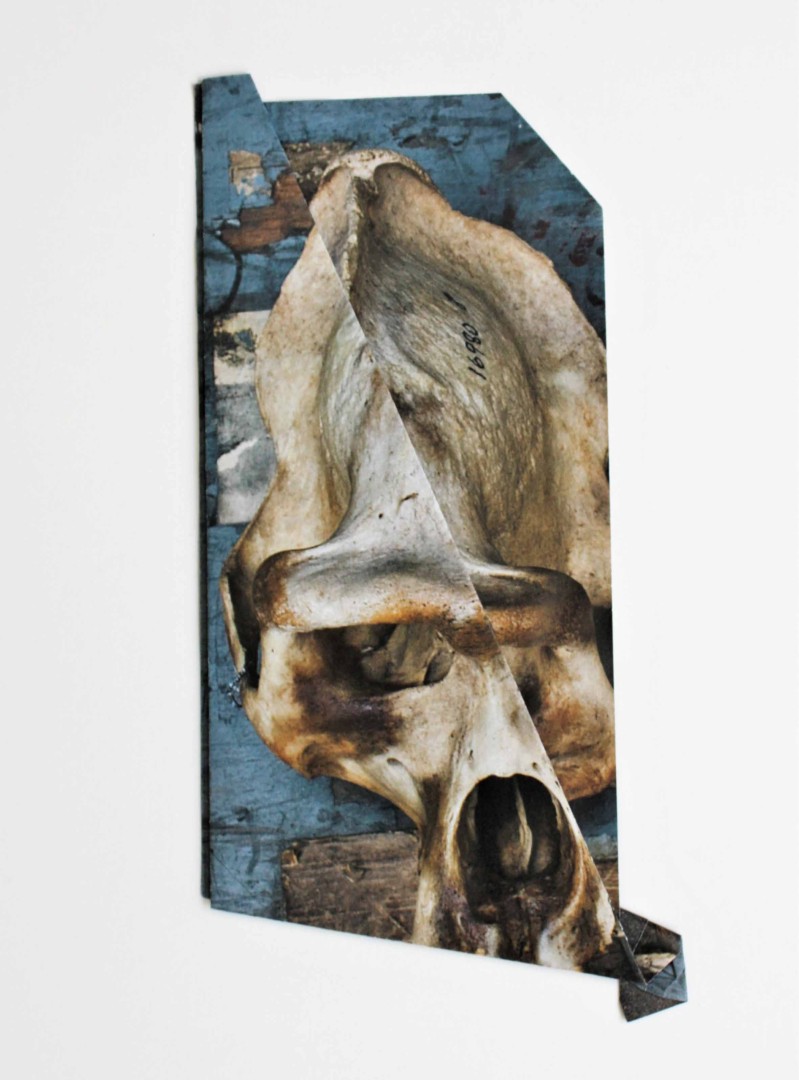

Frieze 4 (closest to the floor), meditates on war, lament, disdain for human life and death. It includes images of two skulls documented as artefacts of a civil war in Africa folded in mind bending, surreal distortion, which is precisely what extreme acts of violence are, mind bending, surreal distortions of humanity.

With these friezes I am again reminded of Žižek’s call for a less direct, sideways view of violence, one that lessens our image-weary capacity to switch off, thereby enabling a greater empathic response. In Tserionis’ Mature Topgography the images themselves are not horrific but their implications are even more frightening.

Toward the end of his opening text in the exhibition catalogue The construction (of History) is the work, 13 Emmanuel Mavrommatis (Emeritus Professor at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and President of AICA Hellas) considers the construction of history as the selection of associations that form one (or more) sequence. He highlights dilemmas associated with processes of selecting the associations to be sequenced. As he does he poses the rhetorical question ‘which are the associations that will be used as sequences?’ The answer to that historically recurrent question, now more than ever, is up to each and every one of us.

Footnotes

1 Papadopoulou, Bia. On History. In Theorimata 2/2020: On History. Athens: AICA Hellas, 2020. p.12

2 These lines are borrowed from an analysis of the painting The Fall of Icarus (1560) attributed to Pieter Breughel the Elder focusing on the idea of a temporal ‘multiverse’, an ‘asynchronous’ and ‘syncronising’ ‘looping mechanism of time’ in The Postclassicisms Collective, Postclassicisms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2020. p.164

3 This passage is indebted to The Postclassicisms Collective who point out that Serres’ conception of ‘liquid history’ aligns with Friedrich Nietzsche’s ‘untimely’ first presented in his second Untimely Meditations (“On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life”) (1874). For more on Serres’ conception of liquid history see Chapter 2.8 Untimeliness in The Postclas- sicisms Collective, Postclassicisms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2020, and Holmes, Brooke. Liquid Antiquity, ed. B.Holmes and K. Marta, Geneva: DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art. 2017. pp.18-59

4 The terms in italics are borrowed from Chapter 2.8 Untimeliness in The Postclassicisms Collective, Postclassicisms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2020. pp.164.180

5 Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. Trans. (authorised by) Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. New York: Zone Books.1991. p.78

6 Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘L’articolo delle lucciole’, Saggi sulla politica e sulla società, ed. Walter Siti and Silvia De Laude, Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1999 (originally written in 1975), pp. 404-411. For more on the contrast between ‘minor’ and ‘grand’ narratives see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, trans. Dana Polan, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986, and Jean-François Lyotard’s introduction to his book The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. G.Bennington and B.Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984, pp. xxiii-xxv.

7 Gardner, Anthony. Lucciole in Andrew Hazewinkel:The Acqua Alta Project. Melbourne: Narrows Publishing. 2010.

8 Georges Didi-Huberman, Survivance des lucioles, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2009.

9 Žižek, Slavoj. Violence: Six Sideways Reflections New York: Picador. 2008. p.4

10 Reference to the Volanakis painting installed in the current Greek Prime Minister’s office was included in an audio visual presentation of historical images and texts related to the Battles of Salamis and Marathon presented as part of the exhibition The Great Victories: On the Boundary of Myth and History at the National Archaeological Museum Athens.

11 Holmes, Brooke. Liquid Antiquity, ed. B.Holmes and K. Marta, Geneva: DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art. 2017. p.31

12 Papadopoulou, Bia in Theorimata 2/2020: On History. Athens: AICA Hellas.2020 p.80

13 Mavrommatis, Emmanuel. On History: The construction (of history) is the work in Theorimata 2/2020: On History. Athens: AICA Hellas, Athens 2020. p.15

The author extends appreciation to all of the artists and curators that participated in Theorimata 2/2020: On History, especially the project’s conceptual curator Bia Papadopoulou. Thanks are also extended to Kaspar Thormod Assistant Director and Carlsberg Fellow at the Danish Institute at Athens, Stavros Paspalas Director of the Australian Archaeological lnstitute at Athens, Anthony Gardner Professor of Contemporary Art History, Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford and to The National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens. All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise credited.

Participating artists and curators included - Alexandros M. Pfaff selected by Maria A. Angeli. Vicky Tsalamata, Antonis Choudalakis selected by Dionissia Giakoumi. Marina Gioti, Aristeidis Lappas, Thanasis Chondros – Alexandra Katsiani selected by Sozita Goudouna. Klitsa Antoniou, Yioula Hatzigeorgiou selected by Antonis Danos. Anastasis Stratakis selected by Charis Kanellopoulou. Yorgos Lazongas, Fotini Poulia, Angelos Skourtis selected by Artemis Kardoulaki. Marios Spiliopoulos, Tassos Triandafyllou, Ersi Hatziargyrou selected by Vassia Karkayanni-Karabelias. Annita Argyroiliopoulou, Irini Diadou selected by Lena Kokkini. Maria Andromachi Chatzinikolaou selected by Magda Koubarelou. Mary Christea selected by Tassos Koutsouris. Filippos Vasileiou selected by Christoforos Marinos. Ersi Venetsanou, Costas Vrouvas, Evi Kirmakidou selected by Emmanuel Mavrommatis. Nikos Giavropoulos, C o s t i s selected by Konstantinos Basio. Georgia Kotretsos & Panos Tsagaris selected by Maria Nicolacopoulou. Eleni Lyra, Efsevia Mihailidou, Dimitris Skourogiannis selected by Stratis Pantazis. Eleni Τzirtzilaki, Giorgos Tserionis, George Harvalias selected by Bia Papadopoulou. Dimitris Alithinos, Angelos Antonopoulos, Yiorgos Tsakiris selected by Miltiadis Μ. Papanikolaou.Dimitris Zouroudis, Kyrillos Sarris selected by Niki Papaspirou. Alexandros Georgiou, Pelagia Kyriazi selected by Spyros Petritakis. Georgia Sagri, Eliza Soroga, Filippos Tsitsopoulos selected by Constantinos V. Proimos. Takis Zerdevas, Constantinos Massos, Efi Fouriki selected by Athena Schina. Pandelis Lazaridis, Erato Tagaridi, Paris Chaviaras selected by Faye Tzanetoulakou. Georgia Damopoulou, Nikos Papadimitriou, Ilias Papailiakis slected by Lina Tsikouta. Makis Faros – Zoe Pyrini Group selected by Anna Hatziyiannaki. Kostas Tsolis selected by Kostas Christopoulos.