The Past is Now: Yiorgos Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity

National Archaeological Museum Athens - 09 May 30 Nov 2022

An illustrated PDF of the text is available here

“All the past is forever present” 1

Yiorgos Lazongas (1945- 2022) must be understood as one of the most significant Greek contemporary artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His exhibition The Past is Now presented at the National Archaeological Museum Athens (the last exhibition of his work to be presented during his lifetime) brought eighty-one of his materially and methodologically diverse artworks into spatial and conceptual dialogue with twenty-three ancient objects from various departmental collections of the National Archaeological Museum Athens (NAM).

Lazongas’s artistic quest was focussed on, motivated and driven by the pursuit of the contemporary spirit of antiquity, rather than its material residues. However, it was his lifelong engagement with ancient material culture (and the stories it carries) originating in Greece and other Mediterranean cultures, that provided him with a unique point of departure in reimagining ancient objects as vibrant contemporary devices, in the form of artworks, through which to better understand the present.

Lazongas’ unwavering commitment to expanding our contemporary dimension, via the realm of the past, cannot be overlooked in the decision taken at the highest levels of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports and the NAM, to collaborate with him, and his family, in presenting for the first time to national and international audiences, the work of a significant living Greek artist’s work in dialogue with ancient objects from the National Archaeological Collection. Staged across three of the museum’s large galleries, reserved for temporary exhibitions, and through a unique combination of archaeological and contemporary curatorial practices, the exhibition The Past Is Now ushered audiences into an unexpected environment where the past and the present actively commingled in a sophisticated and accessible manner.

The exhibition also shed light on recent evolutions in Greek institutional thought concerning the conventionally perceived rift between the past and the present, and how vibrant contemporary communities actively embody their cultural heritage; and the roles that these communities play in keeping the past alive in the present by reimagining it in fresh ways. The exhibition signalled a new awareness of the importance of contemporary cultural producers in keeping the past alive, accessible and relevant to contemporary audiences.

This finds concordance with the words and actions of Dr. Lina Mendoni, archaeologist and current Minister for Culture and Sport, who expresses in her introductory text to the exhibition catalogue, “The exhibition of Yiorgos Lazongas at the National Archaeological Museum is a major step, in linking and fusing our cultural heritage with contemporary creation. This is a priority for the Ministry of Culture and Sports today. The country’s cultural capital is a unified whole, and that is how we approach it. We promote our unique cultural legacy together with the work of our contemporary artists, in a meaningful, organic whole.2

Describing the exhibition, Dr. Anna Karapanagiotou, archaeologist and current Director General of the NAM highlights the importance of the exhibition, and more broadly the role of contemporary cultural production, in the current strategic evolution of the NAM as a “multipotential cultural venue” when she states “The exhibition intends to inaugurate the new cultural activity of the Museum, forming dialogue between the present and the past… …to promote a contemporary reading of history and antiquity, linking our cultural heritage with contemporary creation and stressing the continuation of Greek civilization.” 3

The strategic evolution of the NAM also includes an ambitious new architectural expansion program, which has been designed by 2023 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate David Chipperfield, of Berlin based David Chipperfield Architects, in collaboration with Alexandros Tombazis, of Athens based Tombazis and Associates Architects.

Conceptually and curatorially, the Past is Now was structured around three themes that define an arc through Lazongas’ oeuvre, and in which many of his most significant contributions to a new generation of Greek art students have their genesis.

The first of the galleries was conceptually dedicated to Lazongas’ conception of the Mediterranean as an idea not a place. It included ancient objects originating in Greece, Egypt and Turkey in dialogic exchange with drawings, prints, paintings, multi-media works and two vitrines – one containing studies of the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia produced by Lazongas between 1969-1970, and selected drawings, designs and draft mock-ups from Lazongas’ rejected architecture diploma graduation project “On an imaginary museum at Olympia” for the Architectural University of Thessalonike in 1969-1970. The second vitrine contained a selection of draft sketches and finished drawings which Lazongas created in 1984 for two children’s books, the Iliad and Odyssey, (examples of which feature on the front and back covers of this publication).

Lazongas expressed the formation of his conception of the Mediterranean as an idea not a place this way, “The Mediterranean is a coexistence of ideas, sentiments, cultures, ways of life and creation. It is a crossroads of culture, a starting point and a destination. Wherever I travelled, in the Middle East, North Africa, or Europe, I encountered a visual palimpsest of time.” 4 Lazongas’ conception of the Mediterranean as an idea is further explored in the passages that follow, under the subheading The Space Of Opening (Mediterranean Escapes).

Lazongas had profound knowledge of the NAM collection, however his extensive travel throughout the Mediterranean region, resulted in the outcome that certain ancient objects that inspired important bodies of his work are held in museum collections outside of Greece. That (im)practical reality posed the first of many important curatorial dialogues between exhibition’s principle Contemporary Curator, Bia Papadopoulou, independent curator and Contemporary Art Historian, and her collaborating curatorial partner Dr. Evangelos Vivliodetis, archaeologist, Archaeological Curator and Head of the Department of Exhibitions NAM. Between them they resolved to think about the dialogic exchange between the contemporary and ancient artworks as one based on the ideas presented and explored in Lazongas’ work rather than direct physical association. Working together closely they chose themes and ideas that linked with and enlivened the ancient artworks. Referring to the august institution’s strategy for working with a living contemporary artist Dr. Anna Karapanagiotou, archaeologist and Director of the NAM expressed, “we followed Lazongas”…. “Lazongas was an inspiration for us.” This demonstrates a unique and highly respectful approach taken by an archaeological museum toward contemporary art practice; an approach further articulated by the NAM Museographer and The Past Is Now exhibition designer Bessy Drounga and the museum’s project leader Kelly Drakomathioudaki, who in an interview about the project expressed emphatically to me “whether an artwork is 2000 years old or 20 years old, both must be afforded equally the highest respect.”

The second gallery was dedicated to Lazongas’ conception of the fragment as the whole. In the Lazongian idiom the fragment is associated with the palimpsest and both are intermingled with time and collective memory. In the 1970’s Lazongas introduced the word “palimpsest” into Greek art historical lexicon in order to describe a superimposed layering of images produced at different moments in time. The word palimpsest derives from the Greek word πάλι, meaning again, and ψάω, meaning to engrave. The original material referent being a papyrus, or parchment, from which script had been erased or overwritten by other layers of text thus forming new texts. Over time Lazongas melded his thinking about palimpsests (not only as a word but also as a methodology) with his thinking about the fragment, which he associated with the status of the topos, a space full of debris and vestiges.5 In his own words Lazongas describes the relationship between the topos and the fragment this way “What is this place if not the shattered, fragmented memories and constant absences that crush the initially complete picture? A discontinuous continuity. What are we if not fragments? This lack of the whole picture is the new work.” 6 As one of Lazongas’ principle ideas, this subject is further examined in the following passages under the subheading The Space Of Fragmentation.

The third gallery, which included examples of his most recent works, was dedicated to phenomena of transformation. In the exhibition catalogue, this gallery is contextualised by the statement Metamorphosis: the legitimacy of perpetual change.7 Lazongas expressed the central importance of transformation in his work this way. “Intrigued by ancient vase painting and the austerity of Egyptian aesthetics I devoted a great many drawings to the female figures of Greek mythology, whose forms appear in numerous transmutations. This potential for metamorphosis moved and challenged me, seeing as these mythological heroines transgress boundaries. I portray animalistic behaviour with the female Centaurs I invent and the cultic and orgiastic behaviour of the Maenads. There are drawings of bird-like Sirens, the wet nursing Ephesian Artemis, the beautiful, scintillating bisexual goddess, whom I associate with contemporary womanhood. I think that without the female body and it’s presence-absence, I would not have painted anything.” 8 As another of the guiding principles of Lazongas’ practice, transformation is further explored in the following passages under the subheading The Space Of Transformation.

The Space of Opening (Mediterranean Escapes)

My work contains references to the ancient times, not only to Greek antiquity and its universal symbols but also a dialogue with the past and present of Mediterranean countries. The Mediterranean is a coexistence of ideas, sentiments, cultures, ways of life, and creation. It is a crossroad of cultures, a starting point and destination. Wherever I travelled, in the Middle East, North Africa or Europe, I encountered the visual palimpsest of time. During my travels, I studied the adventure of the line in the East and the West, from the time of the white lekythoi to the present day. I travelled to Egypt seven times. I would love to live in the Museum in Cairo. Dark voices and revealing, that came to me during my numerous travels and research gave birth to images and to shapes of script and speech. I wanted to render in painting what I experienced and to preserve the Krypton (that which is hidden), the Alekton (the unsaid), The Silence. I don’t know if I have succeeded, but these countless drawings and paintings seek to house the idea of continuity I have as a contemporary artist.9

Two of the conceptual foundations of Lazongas’ oeuvre are conceptions of non-linear time and transgenerational collective memory. Both of these complex topics are briefly considered here within the context of remote Mediterranean pasts, they are included here as examples of the type of conjured associations, the immaterial traces and presences that Lazongas searched for and worked with to synthesize the past in original, beautifully enigmatic ways, revealing the contemporary spirit of Mediterranean antiquity.

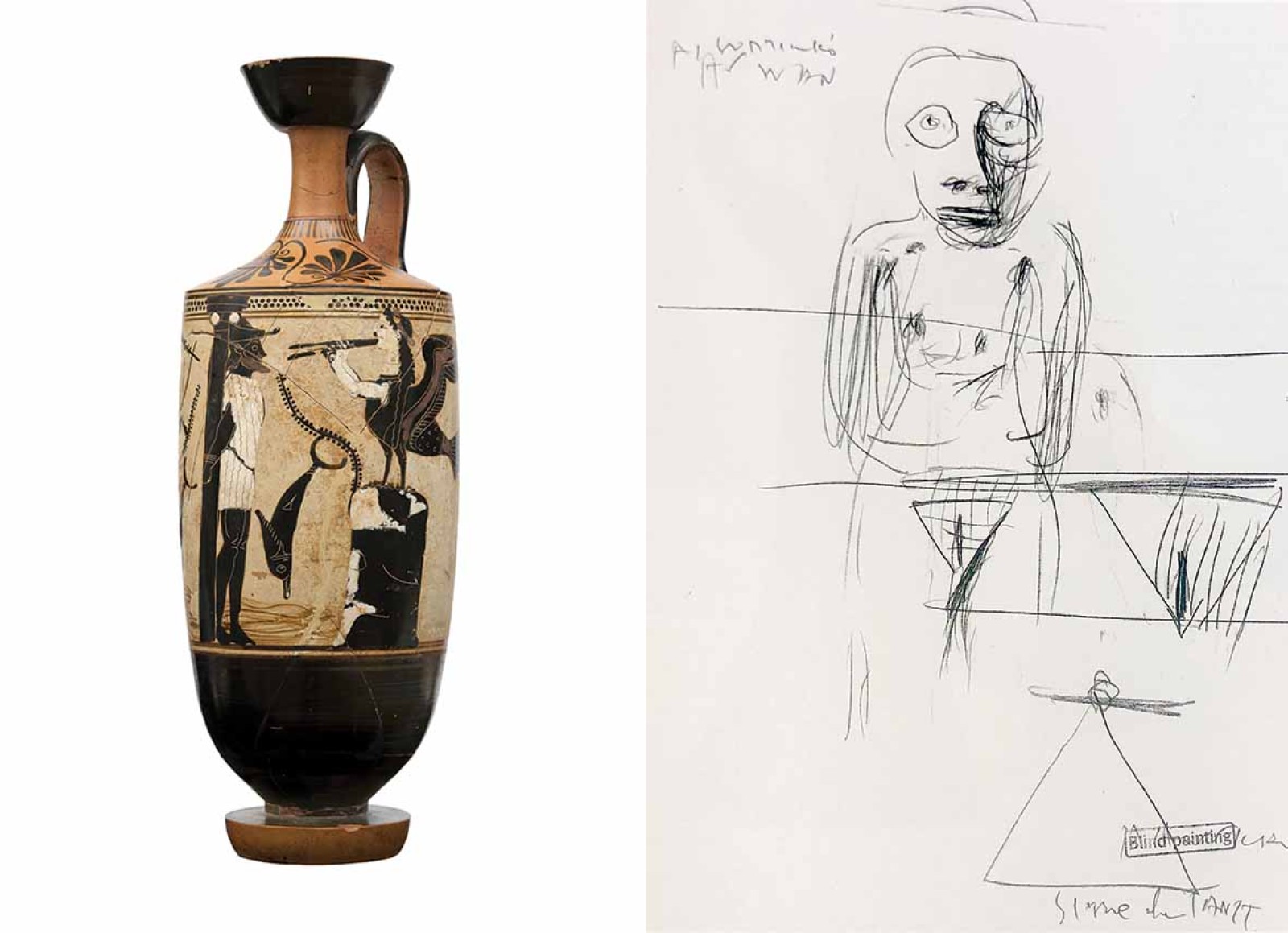

Immediately to your left as you entered The Space of Opening (Mediterranean Escapes) was Odysseus, bound to the mast of his ship, holding out against the famed seduction of the Sirens. Rendered in stasis (in much the same way that a photograph captures narrative) this narrative is playing out for eternity across the curved surfaces of a late 6th c. BCE black-figure white-ground lekythos. It is described in the exquisite line-work and restrained colour that is attributed to the artist, known to archaeologists and historians of ancient art (somewhat inappropriately when considered in the context of today’s important decolonisation of museum collections discourse), as the Edinburgh Painter.

Immediately to your right as you crossed the threshold, was a group of modestly scaled, framed drawings representing transcultural deities and protagonists drawn from mythologies shared across the Mediterranean. The drawing that transfixed me (pictured here) represents Astarte the Hellenised form of Attart the Canaanite/Phoenician gender diverse god(dess) of love, sex, war and hunting, who developed from Mesopotamian Ishtar before eventually evolving into Aphrodite.

This cluster of dynamic, rapidly produced drawings was my first introduction to the masterful draughtsmanship of another Greek painter, Yiorgos Lazongas.

As the keepers of the special threshold into what I call The Space of Opening, these two artists are simultaneously linked and separated by roughly 2500 years of practice. The threshold itself manifests in the dialogue between their exquisitely rendered entities and scenes from evolving mythological narratives. Crossing this threshold induced, perhaps unconsciously, the opening of ones eyes, the opening of ones mind, the opening of ones imagination and the opening of ones heart to the Lazongian universe.

Singular conceptions of quantative time tend to dominate today, however alternative calculations of time still exist, sometimes in localised simultaneous multiplicity. Such is the case in contemporary Iran where three different calendars coexist. For example, today (as I write) is 10 March 2023 according to the Gregorian calendar, it is also 17 Sha`ban 1444 on the Hijri (Islamic) calendar and 19 Esfand 1401 on the Persian solar calendar (Jalaali). 10 There are ancient antecedents to simultaneously diverse ways of thinking about and recording time. In Greece during antiquity for example the names of the month differed between Athens and Corinth and the year, indicated with name of a functionary, sometimes varied from place to place. In Sparta it was the ephors, in Athens archons, and in Argo the priestess of the goddess Hera. In his recent essay Short Circuits: When (Art) History Collapses 11 archaeologist and Art Historian Prof. Salvatore Settis makes the point that the simultaneity of differing temporalities does not nullify the linear course of time, rather it renders it more complex and elusive. 12 It was precisely this complexity and elusiveness in which Lazongas searched for ways to reveal the contemporary spirit (or essence) of Mediterranean antiquity.

Lazongas’ travels throughout the Mediterranean region were not holidays as such, rather research trips. In his own words he explains a common finding reconfirmed again and again on every trip on which he encountered ‘a visual palimpsest of time.’ He visited Cyprus and went on to create important works exploring his conception - the fragment is the whole- with images of Mycenaean pottery from Cyprus. I cannot be certain if he was aware of the Assyrian name for the Mediterranean, or for the island we now call Cyprus, but the following passage presents us with another example of the type of historical information that Lazongas engaged with in his contemporary reimagining of remote Mediterranean pasts.

During the reign of their King Esarhaddon (680-669 BCE) the Assyrians referred to the Mediterranean as “sea of the setting sun” which they conceived as a unified geographical space with Cyprus (Iandana) as a point of reference in the “middle of the sea of the setting sun” however, as noted by Dr. Panos Christodoulou assistant professor, Hellenic Studies, European University Cyprus, the expression was never purely geographical, rather it was used as a kind of dynamic “mental map” of endless transformation.

Contemporary geo-political debates and “ideological modern constructions” concerning whom, or to what, or where Cyprus belongs - the “east”, the “west”, “Asia”, “Europe” - miss the poetic complexity and beauty of the ancient Assyrian description.13 The spirit (or pulse as I prefer to call it) from which the Assyrian conception of the Mediterranean emerged is an example of what Lazongas pursued on his travels throughout the region, later deploying it in his studio, upon his return to Athens, in his idiosyncratic processes of reimagining the now fragmented residues, traces, and presences of the ancient spirit of the Mediterranean.

Between 1976-77 at the Louvre Museum, Lazongas fell under the spell of the Nike of Samothrace (c.200 BCE), a fragmented Hellenistic sculpture excavated from the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on the northern Aegean island of the same name. The now famous sculpture became his source of inspiration for one of his most important bodies of work, titled “Nikae”. Despite his passion for the beauty and forward projection of the headless winged figure, Lazongas chose not to focus on its objective form rather the ideas conveyed by and psychological associations raised by the personification of Victory as a winged goddess. It is important here to understand the ways in which Lazongas found resonances between his artistic practice and the object biographies (or life-journeys) of ancient objects from antiquity to our contemporary realm. The Nike of Samothrace was originally carved as separate blocks of marble ultimately assembled on site as a ‘complete’ figure. This (Hellenistic) sculptural methodology rendered the statue vulnerable to earthquakes, which is how it is believed the figure collapsed. Various fragments were unearthed during successive 19th and 20th century excavations, helping the gradual reconstruction of the striking figure of a winged goddess standing on the bow of a warship. Lazongas was fascinated by the constantly changing (or becoming) ancient sculpture as it mirrored his own conceptual conception of rupture (or catastrophe) as central to artistic creation.

While moving further and further away from the ancient object through processes of deconstruction and reconstruction he remained focussed on the ideas and psychological associations he saw embodied in and by the figure. In this way we can think of Lazongas’ process as working in directions oppositional to that pursued by classical archaeology, yet unearthing important sympathetic knowledge.

In her essay Masculine values, feminine forms: on the gender of personified abstractions 14 Emma Stafford points out that while it is widely understood that personifications of abstract qualities abound in Greek literature and art, what is often overlooked is that the vast majority of them are female. She explains that the represented values fall into various conceptual typologies – social goods, ethical qualities, physical conditions and ‘undesirable’ qualities such as Madness (Lyssa) and Strife (Eris). “Ambivalence” is also represented, by Nemesis (Retribution) and Peitho (Persuasion); however by far the most commonly used personifications are positive ‘good things’, exampled by terms for prosperity/ happiness (Eutychia, Eudaimonia), Peace (Eirene) Democracy (Demokratia), Health (Hygieia), Justice (Dike), Glory (Eukleia), and Victory (Nike). Identifying a paradox, Stafford stresses an accompanying irony in the fact that given the status of women in ancient Greek society, qualities deemed so desirable by Greek men should be represented in female form.15

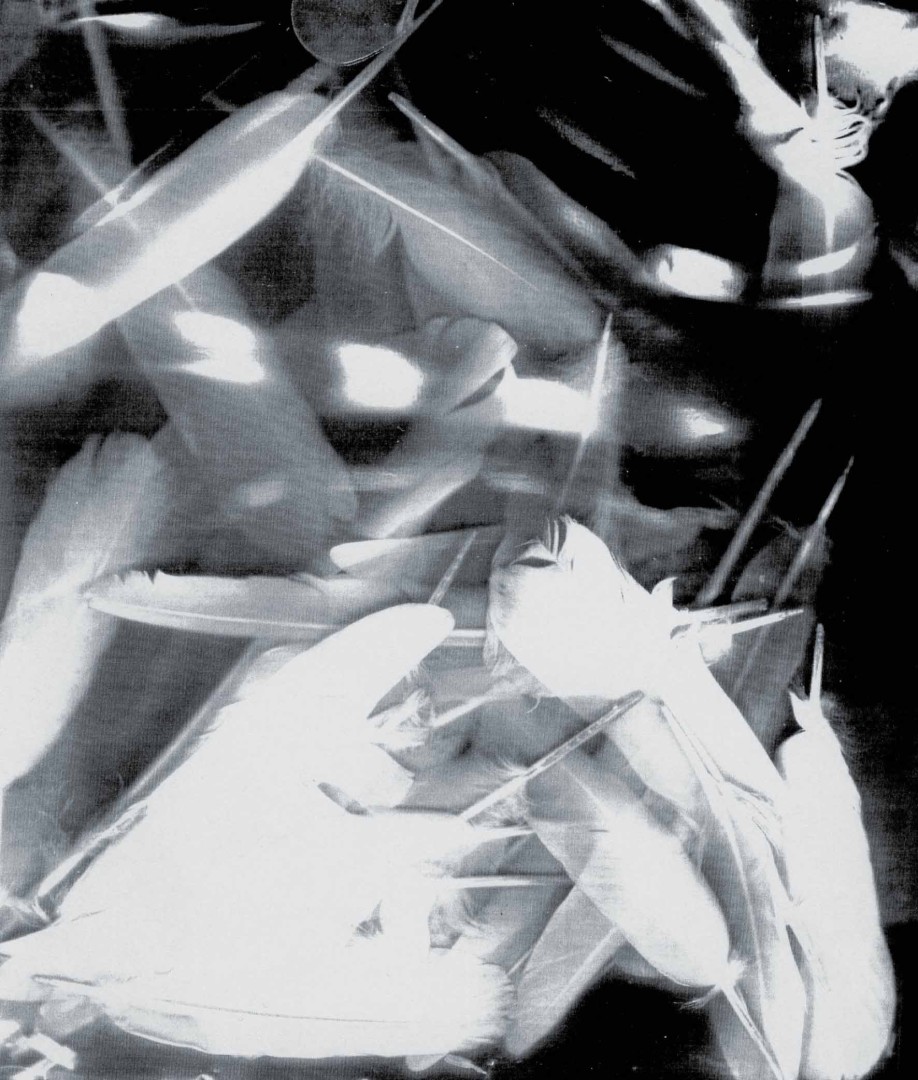

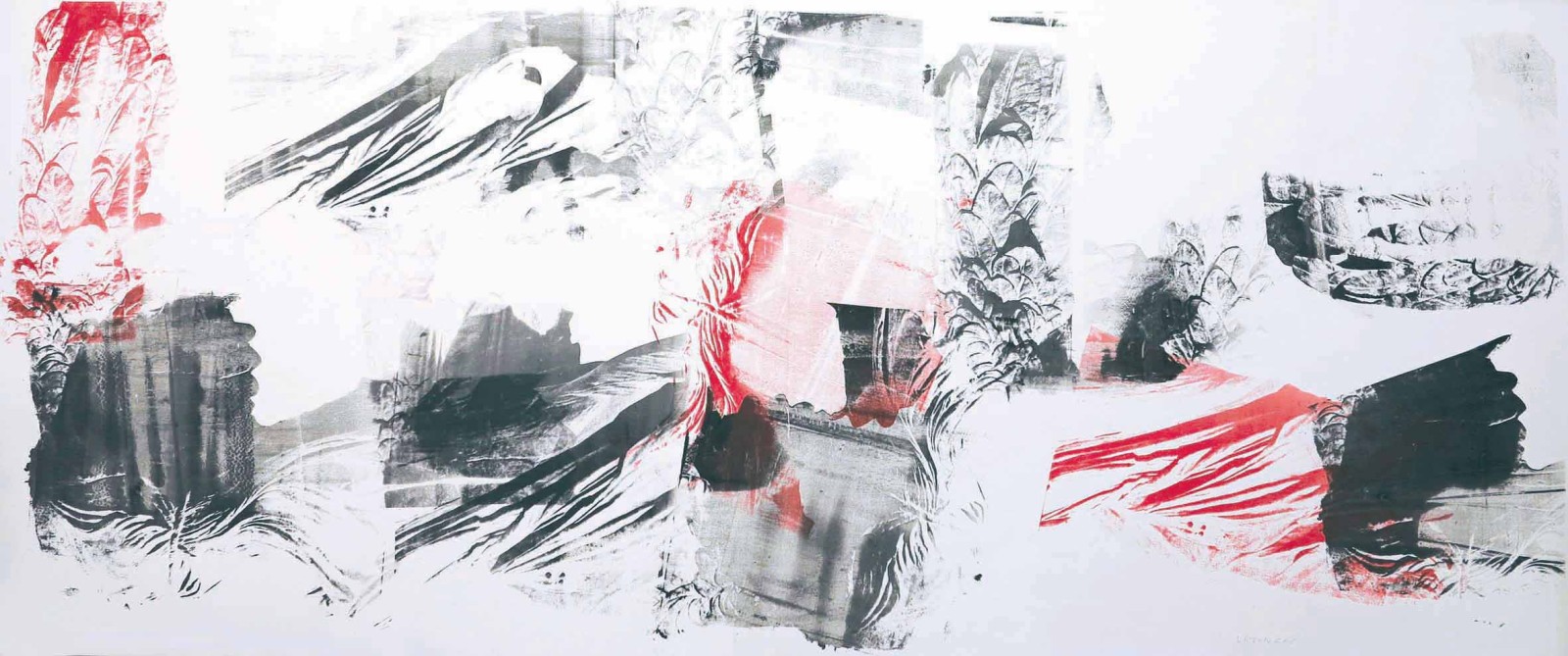

Lazongas’ expansive Nikae project occupied him for two decades over which time he returned to his subject again and again, moving further and further away from the physical ancient source while deepening his exploration and reimagining of the “spirit”, or the aroused psychological associations of exquisite hybrid anthropomorphic / zoomorphic female form, through manifold artistic processes executed with a multitude of materials. Collage, blind painting, bed sheets, chocolate, photography, projection, installation, spray-paint, drawing and plexiglass are all deployed in Lazongas’ Nikae series.

The later works in the series, inspired by the exquisite carving of the fabric on the goddess’ stone body, are made using a wet fabric technique. In making these works Lazongas places white sheets over his naked models who assume various horizontal poses, he reveals their presence through the application of various materials directly onto the wet sheets; early versions of these works were made with chocolate, later versions with spray paint. These ‘lived in’ bed sheets suggest secrets and perhaps reveal the Alekton (the Unsaid), reminding us of the fleetingness of our own existence and the sensual qualities of our ephemeral existence. Describing the transformational arc of the Nikae series Papadopoulou states “The winged goddess of ‘Victory’ gradually mutates into a contemporary emblem of love (eros) as well as a life-death allegory. The shifts of the models’ bodies under the sheets bespeak of covert symbolisms. Their postures allude to experiences of deification; in other instances, they recall the crucifixion or the deposition from the cross. The works embody experiences, convey lust but also trauma, hint at every human’s ‘via dolorosa’. The sheet itself is an allusion to Jesus’ Holy Shroud, an earthly attire that awaits even the most victorious of people as time advances mercilessly.” 16

The Space of Fragmentation

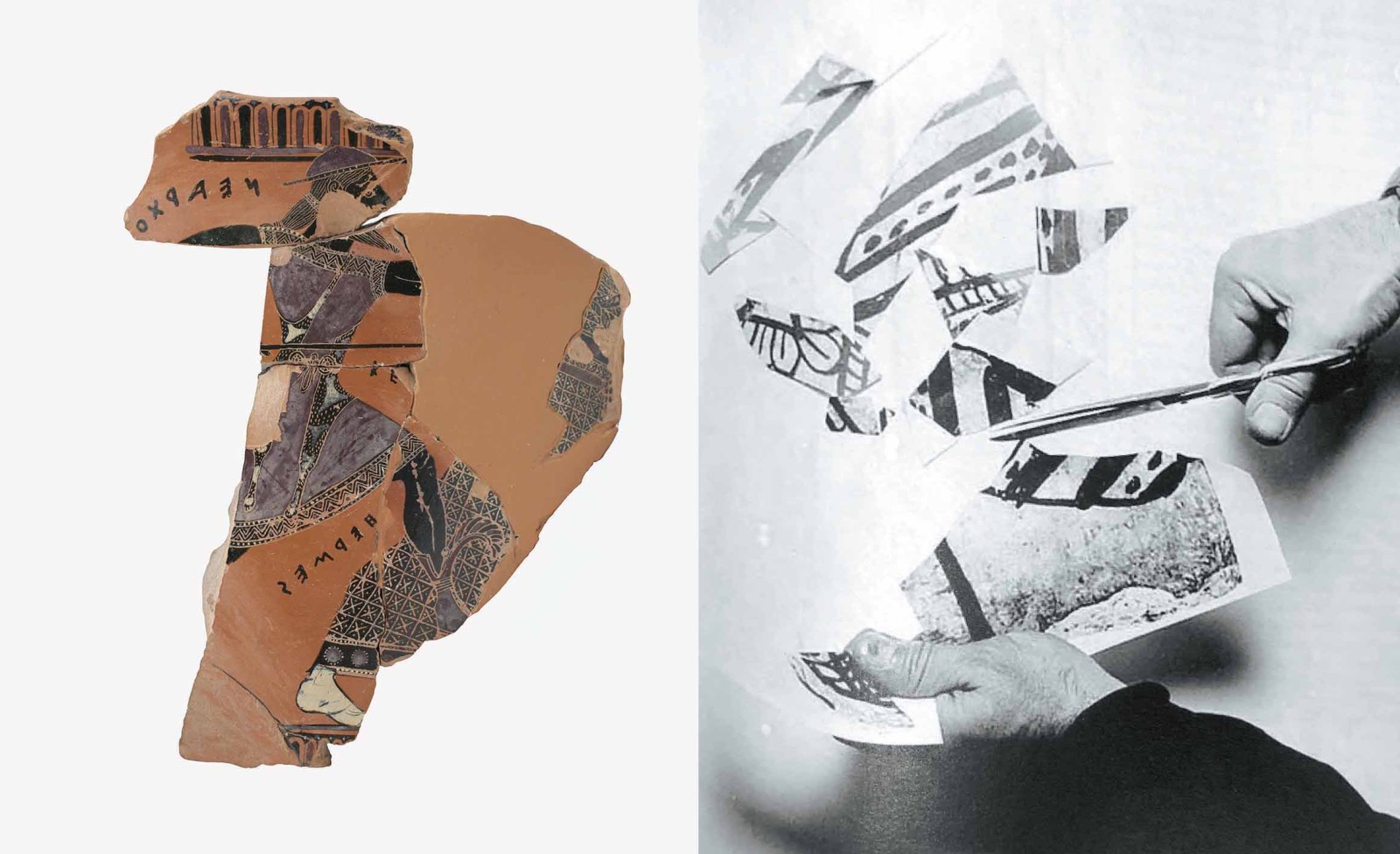

The work is an enigma that contains its own solution, regardless of whether the image is lost so that it can reappear anew. It happens, as in a palimpsest, where script and its negation are contained in perpetuity. The ancient vessel no longer depicts itself; it belongs to history. I clipped photographs and cut up images with the curiosity of a child destroying a toy. The cut-up pieces of paper took the place of painted volumes or their shadows. The process fit the myth. The fragment- shard, the trace, too – they converge in the idea of origin, they don’t rant or rave, or become lost. The metaphor maintains old myth as an illusion. Whether we wish so or not, the reference to the archaic ensures an unbroken continuity of time, place, and image.17

“Catastrophe is part of the cultural product. We grew up among stones, statues and fragments of a civilization that, while it ceased to be what it depicts, it continues to tell us its story” 18

These two statements (made by Lazongas toward the end of his life) deepen the enigmatic complexity of one of the great thought engines of his artistic practice “ the fragment is the whole.” This conceptually vast, paradoxical, five-word premise is perhaps Lazongas’ greatest liberating philosophical and artistic legacy. In the Lazongian idiom the fragment is the whole because it preserves the memory intact by occupying a kind of hybrid conceptual space between synecdoche and engram.

For Lazongas the fragment was both a methodological device and, in a conceptual sense, a reference to the status of the topos and the mainstay of a broader worldview centred on human existence.

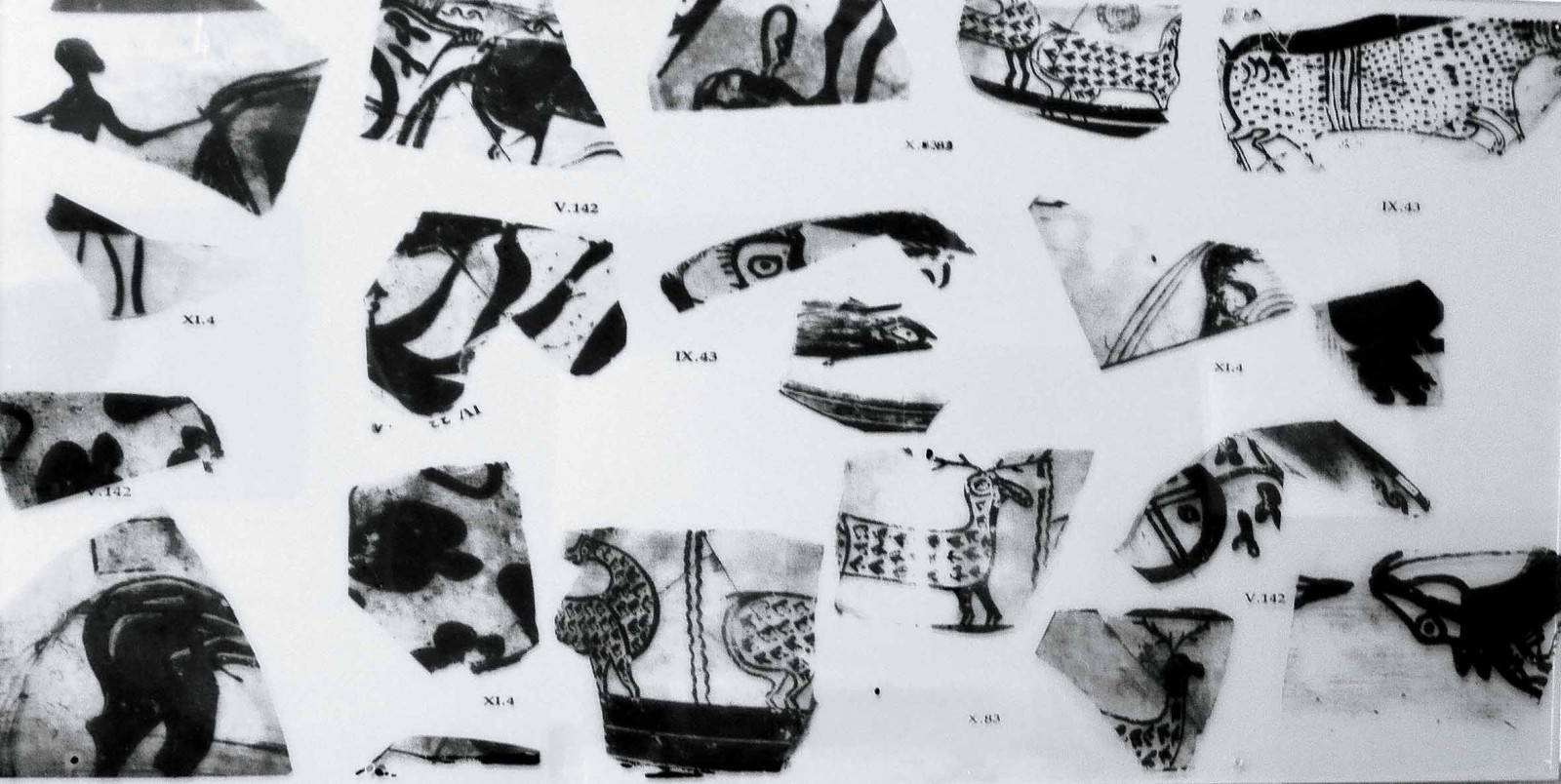

In the second gallery (The Space of Fragmentation) audiences were introduced to the developmental trajectory of Lazongas’ deployment of deconstruction as methodology. It featured a suite of large paintings, prints on plexiglass (which deploy shadow as a critical conceptual component and formal visual element), and two vitrines, one dedicated to Mycenaean pottery sherds from Cyprus representing anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms, the other representing epigraphic sherds.

As Dr. Evangelos Vivliodetis Archeological Curator of The Past is Now points out, Lazongas’ conceptual premise of the fragment is an example of interdisciplinary conceptual alignment between the science and practice of archaeology and a contemporary artist’s worldview. 19

We can think about Lazongas’ deconstruction / reconstruction of an image as inserting an alternative temporality into an existing one. This way of thinking about rupture as creation, draws us toward the archaeological concept of spolia, on which Salvatore Settis, recently wrote “The intersection of incompatible temporalities presupposes and presents a sort of de-historification of time; it activates the convergence, but also challenges, among parts (coexisting and discordant) of one same tangible creation.” 20

Lazongas’ exploration of ideas and his interrogation of the latent expressive potentials in processes resulted in bodies of work that often spanned decades. Lazongas began thinking about the fragment in 1969 as a student of architecture at the Aristotle University of Thessalonike while preparing his thesis “An imaginary museum at Olympia” which is where the fragment first appears in his work. His thinking on and use of the fragment in his work deepens in the 1970’s following his study of the Naxos frescoes and the stratifications from the era of iconoclasm. 21 In the 1980’s, alongside installation, photographic and performance practices, writing, which had for some time been a complementary aspect of his artistic practice, entered his works directly and with great force. He drew/wrote with fragmented words recalling unintelligible sibylic augury, and arranged oppositional concepts in graphic tables that functioned as ‘whole making’ pairs of positive and negative. In this period he worked extensively with carbon paper, drawing and writing ‘blindly’ through it. In the ‘90’s Lazongas turned to fragmented material culture as a subject, often working at very large scale he began painting columns, these iconic works exert for me powerful resonance with the female human body. In the early 2000’s, while building his residence -cum- studio in Kerameikos (an undertaking which spanned a decade), he began his “Fragments-Shards” series of paintings and prints on plexiglass inspired by the Mycenaean pottery shards he had experienced in Cyprus. He composed and printed archaeological photographic documentation of sherds onto plexiglass, through which the viewer experienced a trace, shadow-projection evoking a ritualistic dance, fusing the material and the immaterial. Described here in his own words, “ I use pottery sherds suspended in a space in a kind of reattachment in which they redefine themselves. The fragments long for connection. It is a symbiosis that creates the notion of an aide-mémoire as the driving perception of wholeness that is each present moment.” 22

The Space of Transformation

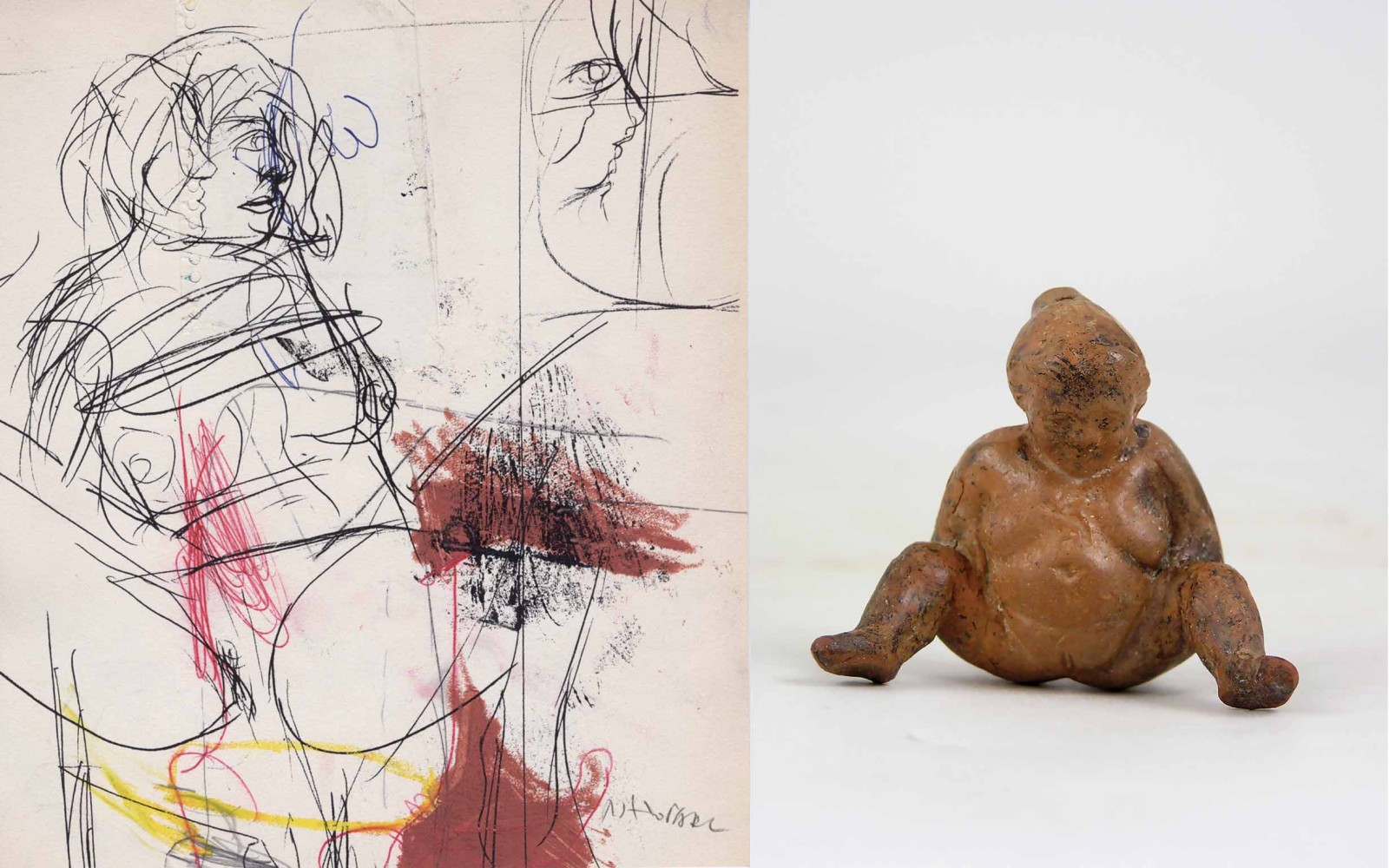

Intrigued by ancient vase painting and the austerity of Egyptian aesthetics I devoted a great many drawings to the female figures of Greek mythology, whose forms appear in numerous transmutations. This potential for metamorphosis moved and challenged me, seeing as these mythological heroines transgress boundaries. I portray animalistic behaviour with the female Centaurs I invent and the cultic and orgiastic behaviour of the Maenads. The drawings of birdlike Sirens, the wet-nursing Ephesian Artemis, the beautiful, scintillating bisexual goddess, whom I associate with contemporary womanhood. I think that without the female body and its presence-absence, I would not have painted anything. 23

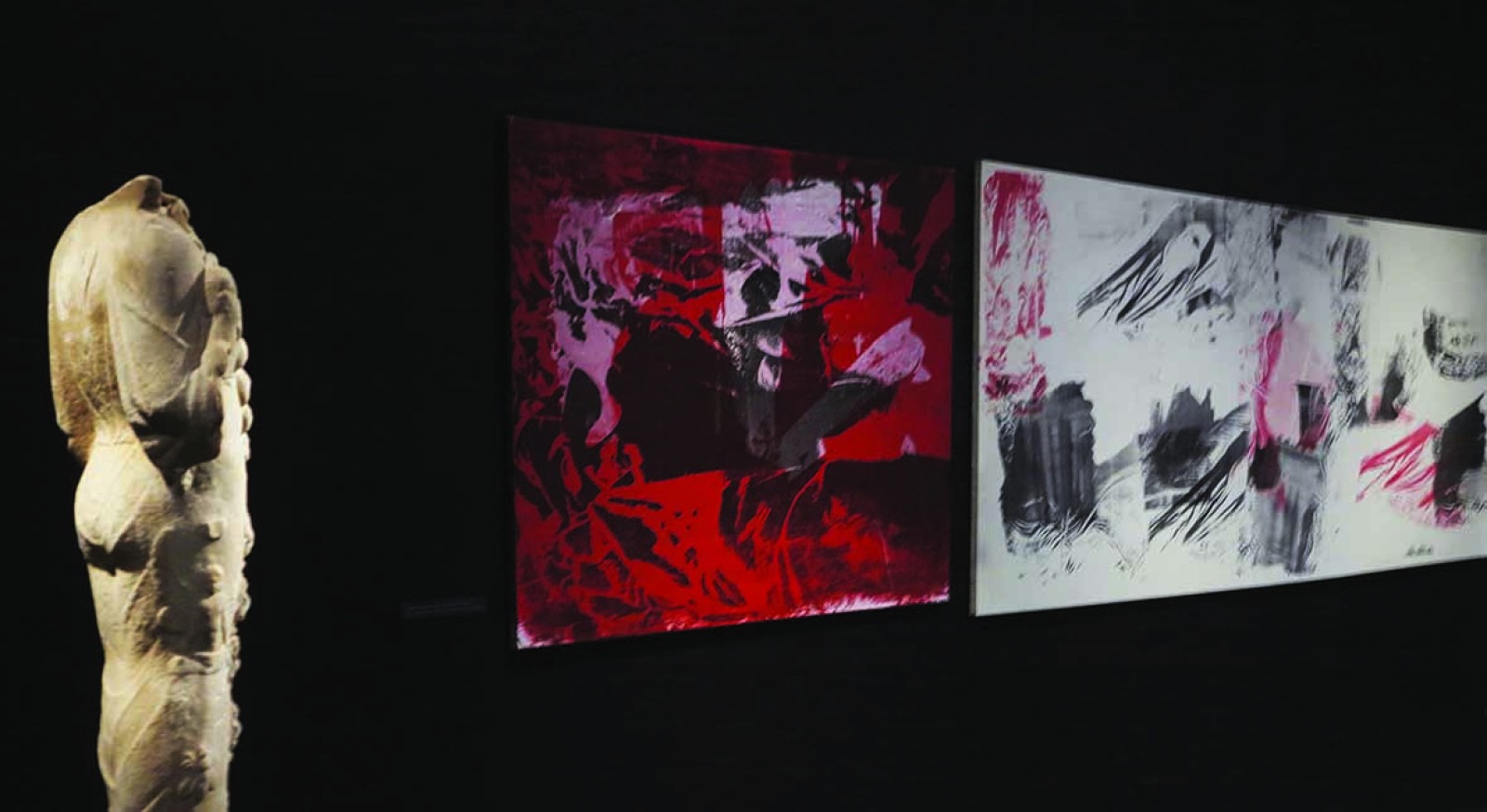

The third and by far the most enigmatic space of the exhibition was dedicated to phenomena of transformation, which as Papadopoulou points out is as central to Lazongas’ work as it is to mythology.24 Here we entered a darkened space, two of Lazongas’ drawings from the 2008 series “Sirens” (depicting birdlike Sirens free-falling though the air to their death), are projected in fine bright white line onto two panes of darked plexiglass that were suspended from the ceiling. The two panels flanked a Pentelic marble funerary statue of a Siren, 330-320 BCE 25 from the Ancient cemetery of Kerameikos, which is not more than 100 metres from Lazongas’ home and studio. The illuminated lines of the free-falling Sirens reflected onto the floor, the ground became the sky, we stood on an unstable ground, there was brightness flickering in the background, death was imminent.

This strangely solemn space was populated not only by Sirens, but also other female figures and deities, which collectively formed a chain of transformation. Nikae transformed into demonic Sirens, symbols of danger, devastation and death. Isolated from their mythological context here they were represented as monstrous and provocative women, either alone or in groups. In his essay The Punishment of the Sirens, Dr. Efthimis Lazongas, archaeologist, Art Historian and the son of the artist, points out that the Homeric Sirens do not have faces, while their Kafkian versions resemble monsters with “arched neck, deep breath, tearful eyes, half open mouths, nasty hair, curved nails”. He goes on to state “similar figures arise in Lazongas’ work, more or less monstrous, however always enticing”. 26

These Sirens mutate again becoming hybrids with women’s heads and the bodies of birds of prey. This figuration has antecedents in Egyptian art which undoubtedly Lazongas was drawing upon. Efthimis Lazongas further explains in his afore mentioned essay “ To the ancient Greek imagination the Siren is not associated only with a demon of death or the archaic fantasy of a voracious female, but also with the depiction of the soul that already since Egyptian art was depicted as an anthropomorphous bird or muse of the Underworld that knows the deeper essence of existence and of life.” 27

From the proliferation of images of Sirens that exists, Lazongas focused on the singular representation of a bird-like Siren in free-fall (from the Attica stamnos depicting the tribulations of Odysseus that was found in Etruria and currently resides in the British Museum). Over and over again he drew her floating, twisting, falling through the air. Rather than confront the end of these doomed Sirens Lazongas transformed them again, into the mythical mutation of lambe in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter – Baubo, a symbol of the mythical vulva. Little known Baubo succeeds in making Demeter laugh during her search for Persephone by revealing her gentials thus lightening, albeit briefly, Demeter’s grief. A provocative and healing gesture. Ancient depictions of Baubo represent her naked with her legs spread widely provocatively displaying her genitalia. As is the case in 1st - 2nd c. terracotta figurine-pendent from the NAM collection 28 displayed publicly for the very first in The Space of Transformation. Baubo’s brazen pose captured Lazongas and he painted and drew her again and again, fusing her with erotic memory images fusing personal and collective memory.

In closing I turn to Dr. Sania Papa, Art Theorist, Independent Curator and sometime collaborator of Lazongas. “ Lazongas indelibly imprints ‘incomplete’ traces – the ostensibly (unfinished) meets the archetypal myth of the ‘eternal return’- progressively structuring the total of his multidimensional work. His personal principles / methods of comparative classification, systematic study, research, observation and assimilation of international aesthetic idioms put in motion art itself and its forms, precisely as Aby Warburg constructs on an iconographic and conceptual level through unique unifications, the cross cultural atlas with the title Remembrance. He used the Greek word for Engramma (Εγγραμμα) which characterizes the ‘printed’ trace on the web of collective memory.” 29

Footnotes

1 Yiorgos Lazongas, The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 188

2 Mendoni, L. When the present accompanies the past…The Past is Now. Lazongas. Myths and Antiquity. National Archaeological Museum Athens. 2022. p.13

3 From an interview between the author and Anna Karapanagiotou, Archaeologist and Director of the National Archaeological Museum.

4 Yorgos Lazongas, The Visual Palimpsest of Time, in The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 41

5 In this passage I am indebted to the generous responses to questions I posed to Bia Papdopoulou Contemporary Art Historian and Curator during one of our many conversations concerning the evolution of Lazongas’ practice.

6 Yorgos Lazongas, Randomness as Method, Introduction: Katerina Koskina, EMST, Athens, p.302

7 The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 41

8 Yorgos Lazongas, The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 160

9 Yorgos Lazongas, The Visual Palimpsest of Time, The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 41

10 https://www.iranchamber.com/calendar/converter/iranian_calendar_converter.php

last accessed March 10, 2023

11 In this paragraph I am indebted to Savatore Settis, specifically Salvatore Settis, When (Art) History Collapses, in Recycling Beauty, Foundazione Prada, Milan 2022, p.60-85

12 ibid. p65

13 In this passage I am deeply indebted to Dr. Panos Christodoulou assistant professor, Hellenic Studies, European University Cyprus, specifically for his brief introduction to the exhibition catalogue accompanying the exhibition In The Sea Of The Setting Sun: Contemporary Photographic Practices and the Archive, State Gallery of Contemporary Art –SPEL, Nicosia: Cyprus 11/11/22 – 25/02/23.

14 Emma J.Stafford, Masculine values, feminine forms: on the gender of personified abstractions in Thinking Men. Masculinity and its Self Representation in the Classical Tradition. Ed. Lin Foxhall and John Salmon. Routledge London, New York 1988. p.43-56

15 ibid p.43

16 Bia Papadopoulou, Endless Transformations in The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 21-22

17 Yiorgos Lazongas, The Fragment, The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 100

18 Yiorgos Lazongas, It is all about continuity, a conversation between Anna Michalitsianou and Yorgos Lazongas, in The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 188

19 Paraphrased from interview between the author and Dr Evanglos Vivliodetis Archaeologist, NAM Head of the Department of Exhibitions and Archeological Curator of The Past is Now

20 Savatore Settis, When (Art) History Collapses, in Recycling Beauty, Foundazione Prada, Milan 2022, p.82

21 Anna Michalitsianou, It is all about continuity, a conversation between Anna Michalitsianou and Yorgos Lazongas, in The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 188

22 Yorgos Lazongas in Yorgos Lazongas, Randomness as Method, Katerina Koskina, EMST, Athens, 2018, p.298

23 Yorgos Lazongas, The Permanent Transformation rule in my work, The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity, National Archaeological Museum Athens 2022, p. 160

24 Paraphrased from interview between the author and Bia Papdopoulou Contemporary Art Historian and Curator.

25 Funerary Statue of a Siren. NAM Γ 775.

26 Efthimis Lazongas. The Punishment of the Sirens. Lazongas Sirens, Municipal Gallery of Larissa, 2009 172-177. p.173

27 Efthimis Lazongas. The Punishment of the Sirens. Lazongas Sirens, Municipal Gallery of Larissa, 2009 172-177. p.177

28 Terracotta figurine-pendant 1st-2nd c. BCE Athens NAM A 13008.

29 Sania Papa, Coincidence as rule of the accidental in A4 Drawings, Benaki Museum / Macedonia Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens / Thessaloniki 2006. P 304.

An important component of the research informing this text was a series of interviews and conversations between the author and the people involved in conceptualising, developing and staging The Past is Now: Lazongas: Myths and Antiquity. The author expresses sincere thanks to Dr. Anna Karapanagiotou, Bia Papadopoulou, Dr. Evangelos Vivliodetis, Bessy Drounga, Kelly Drakomathioudaki, Anna Mihalitsianou and Dr. Efthimis Lazongas.

Images of artworks created by Lazongas courtesy of Anna Mihalitsianou. Images of archaeological material courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum Athens.