PgJ

Paul G. Johnston is a scholar of the ancient Mediterranean and its legacies. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University and completed graduate training at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. He is currently a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Stanford Humanities Center and a Lecturer in Stanford University's Department of Classics.

Presence Elsewhere was commissioned by Sumer Contemporary, Aotearoa New Zealand on the occassion of the exhibition Journeys In The Lifeworld of Stones (Displacements I-X) February 2022. It features in the exhibition catalogue which can be downloaded here

In 2002, the directors of eighteen of the most important art museums in Europe and the United States signed onto a now-infamous “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” a brief but vigorous defence of institutions—like most of their own—“whose collections are diverse and multifaceted.” 1 This intervention was motivated by increasing calls for the repatriation of items in the collections of Western museums that were obtained, usually long ago, through illicit and poorly documented means, including theft, looting and smuggling. 2 In making its case, the Declaration suggests that by placing objects in “direct proximity to products of other great civilizations,” these “universal” museums bring into relief the distinctive characteristics of different cultural traditions as well as the sheer variety of human experience. Accordingly, to narrow their collections through repatriation would constitute a “disservice to all visitors.” The Declaration’s arguments rest on some troubling assumptions and oversights, not least the incongruity between their claim that universal museums make material “widely available to an international public” and the near-total geographical concentration of such institutions in Europe and North America.

In the decades since, “universal” or “encyclopaedic” museums 3 —those that “comprise collections meant to represent the world’s diversity, and … organize and classify that diversity for ready, public access” 4—have come under increasing scrutiny. They have found their defenders, most prominently James Cuno, now President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust and formerly the director of a number of major American museums, who has advanced arguments, ultimately grounded in Enlightenment values, that the encyclopaedic museum presents a valuable vision of human culture and history as a universal inheritance available to all, freed from the parochial and ethnocentric claims upon heritage made by modern nation states.5 They have also found their fair share of detractors, who have tended to emphasize how the collections of these institutions are deeply implicated in vast historical power imbalances, in particular those produced by Western imperialism, between the places where the museums are located and the places where much of their collections originated from.6 Moreover, these aspects of their institutional histories have usually been left entirely unacknowledged and uninterrogated within the museums’ public displays. It is undeniable that the world’s universal museums—concentrated in North American and European states with ugly histories of colonialism, militarism, exploitation and empire—obey the logic of imperialism, seeming to imply that the creation and dissemination of knowledge can be centralized and universalized, and moreover that the politically, culturally and militarily powerful nations of the West possess a unique right to catalogue and control the narratives that we tell about the world and the past. These institutions are “products of empires, whose genesis was inherently culpable, as they did not have the moral right to tell a narrative of the world to the world.”7

Recent academic debate about universal museums has moved on from a myopic focus on repatriation,8 and more nuanced perspectives have explored the serious problems inherent in the histories and cultural politics of these institutions even as they also acknowledge the merits of museums that allow for an appreciation of the world’s cultural and historical diversity and enable the recognition of connections between different cultures, geographies and temporalities.9 The question is no longer simply whether institutions can or should atone for their imperial histories by repatriating objects—an important issue to be sure, but only a small piece of the overall puzzle—but also how they might find other ways to expose the troubling aspects of their pasts across all dimensions of their operations.

Interest in the universal museum as a site of reflection is not confined to the discussions of academics, museum directors and other heritage professionals, but has recently become a recurrent focus of activity in contemporary art making and associated curatorial practice. Curators are intervening in traditional museum spaces to rethink how their legacy collections might be re-presented and recontextualised in ways that allow for new kinds of dialogue with perspectives outside of the dominant Eurocentric paradigm, frequently in close collaboration with contemporary artists. Characteristic is Raid the Icebox Now (2019–21), a curatorial project at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, inspired by Raid the Icebox (1969), an influential exhibition at the institution put together by Andy Warhol using selections from its collections store, and one of the earliest and most influential artist-curated exhibitions at a major museum.10 The legacy of Warhol’s project has now inspired a series of artist-led interventions in the RISD Museum’s galleries that interrogate the institution’s collections. This includes, for example, Simone Leigh’s The Chorus (2019), where the artist installed her own sculptures and some selections from the collections store amidst the existing displays in the museum’s Greek, Roman and Egyptian antiquities galleries, accompanied by a sound recording of texts written by women of colour. Leigh’s intervention explored continuities in artistic expression across time and culture and, just as importantly, interrogated the ongoing legacies and contemporary resonances of the cultural imperialism embodied by the archaeological objects on display.

Raid the Icebox Now, along with similar recent artistic and curatorial engagements with the politics of museums, their collections and their institutional histories,11 extends out of “institutional critique” as a major thematic of contemporary art since the 1960s,12 now shaded by the important discussions about the imperialist histories of major museums that have developed since the turn of the millennium.13 Related is a trend in recent decades towards the historical and archaeological as an object of sustained interest in the work of many major contemporary artists and in associated curatorial practice.14 Andrew Hazewinkel’s Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X) can be understood within this context as a potent theoretical reflection on the limitations of the encyclopaedic museum as a space for the display of archaeological material, and the lingering effects of the violent acts of looting and smuggling that allowed for the assembly of these institutions’ collections. The artist’s materially- and experientially-grounded perspective puts the spotlight on a very particular kind of absence that attends archaeological objects held in museums, namely the loss of the highly specific environmental, cultural and spatial context that they once belonged to.

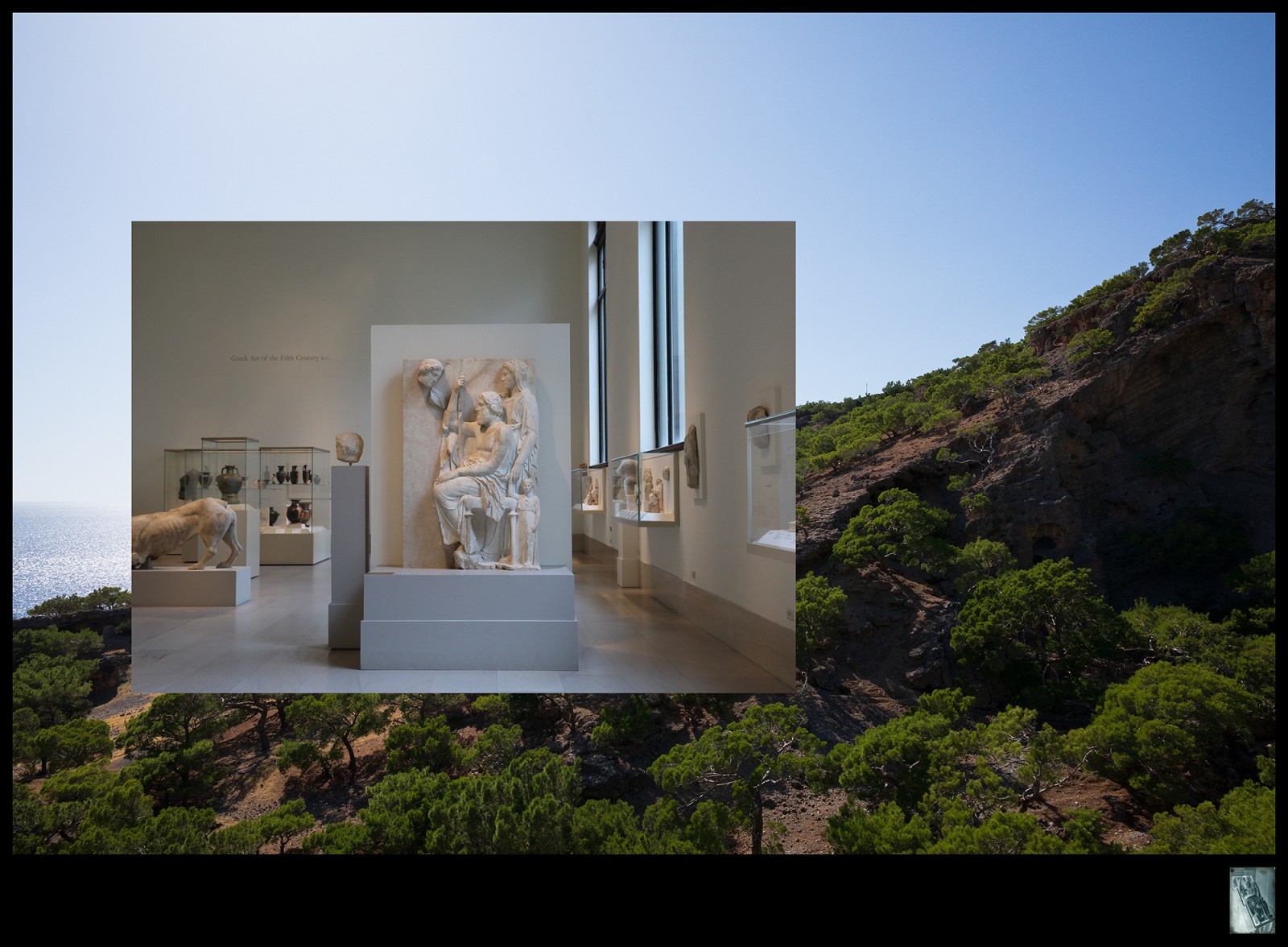

Hazewinkel focusses on a selection of antiquities that now belong to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Originally excavated from various locations in the Mediterranean, their provenances are at best murky and incomplete, at worst practically non-existent. The mechanisms that brought these works to the Met have deliberately erased much of the information about where they were originally found and whose hands they passed through to end up in the Met’s collection. Hazewinkel has photographed his chosen archaeological objects as they appear today in the galleries of the Met, juxtaposing the sterile museum displays against photographs of landscapes, flora, ocean and sunsets from the Mediterranean nations where the objects were originally made and found, suggestively proposing hypothetical origin spots for them. This contrast highlights what is missing from these works in their current home at the Met.

They can be experienced now only partially, divorced not only from the geographic, climactic and social contexts where they were originally found, but also even from specific knowledge of where that find spot was. Knowledge of where, exactly, these objects sat in the earth for thousands of years is irretrievably lost, and with it any sense of how their materiality related to their surroundings. The dynamic relationship between the sculpted objects and the terrain that they originally occupied is gone. They are capable now only of telling a flattened and homogenised version of ancient art history, aestheticized as art objects rather than historicised as cultural artefacts specific to particular locations. This is not necessarily to say that there is no value in the kind of narratives about ancient art that the Met tells, but it is undeniable that it is only a partial narrative, and in many cases any attempts to supplement it with more meaningful social, historical, and geographical context are severely curtailed by the permanent loss of certain kinds of information about the objects.

There is also a quasi-colonial violence implicit in this loss: who has been deprived by the removal of these objects from their homelands? In Greece, a very visceral sense of loss often comes into play when famous objects in overseas museums have an established provenance from a specific place. It feels like something is missing, a piece of local culture and identity conspicuous not only in its absence but also its presence elsewhere. Most famously, the New Acropolis Museum, pride of place in central Athens and a tourist hot-spot, has pointedly left space in its galleries for the so-called Elgin Marbles, sculptures from the Parthenon that have been on display at the British Museum since the nineteenth century, and whose return to Athens has been agitated for by the Greek government since the modern nation declared independence two centuries ago. Everything is ready to go—pending the return of the sculptures to Greece.

The Elgin Marbles operate at the level of national identity—the most famous sculptures from the most famous monument in the capital city, a potent symbol of the modern Greek nation as a whole in its ever-present connection with its ancient past. Yet the same thing happens on a more local level across the country. The island of Milos, for example, proudly but mournfully celebrates its most famous daughter, the iconic Venus de Milo. In the local archaeological museum there is only a plaster cast of the statue, a cruel facsimile of the original in the Louvre.15 Yet even in her absence the Venus acts as a source of collective identity on Milos, a central and defining fact about the island and what it represents. Smaller scale reproductions are ubiquitous in all kinds of businesses and private homes. The loss of an object from its local context is not just a single moment of deprivation: the absence can linger, reverberating across time. While the connection that the islanders of Milos feel to the Venus de Milo is in some sense constructed and artificial, gaining importance precisely because the object has been afforded fame by its presence at the largest art museum in the world, it is also a visceral and meaningful one.

All ten of the objects represented in Hazewinkel’s series entered the Met’s collections in the early twentieth century with the assistance of John Marshall, then the museum’s sole European agent in antiquities. From their varied and poorly attested find-spots across the eastern Mediterranean, they were all channelled through Marshall’s collecting practice. Small reproductions of photographic negatives of each object, commissioned by Marshall as part of the acquisitions process, invoke the moment when they became institutionalised, so to speak: when they gained the status of being members of one of the world’s most important art museums. The negatives connect the ten works into a coherent series: what unites these objects is that they were brought to the Met by Marshall, and the negatives act as a material reminder of this often-overlooked part of their stories. These early photographs also speak to the aestheticizing interests of the museum in the early 20th century: the complex materiality of the objects is reduced to a one-dimensional photograph, the archaeological object stripped of social context and rendered pure visual art.

How do we make meaning out of the objects we unearth? Who controls this process—and who should? Where has the right to? The Met is one of the most visited museums in the world. The strength of its collection in all kinds of areas is undeniable. But in the case of its antiquities collections, at least, the stories that it is able to tell are often constrained by the lack of reliable information about context and provenance. Amidst his institutional critique of the limitations of the Met and other encyclopaedic museums, Hazewinkel seems to advocate for a kind of knowledge and appreciation of ancient objects that is properly situated, grounded in the unique sensorial characteristics of the places that they were found. How might these objects resonate differently if they had been kept closer to home? What would change if they were held in the small local archaeological museums that are dotted all across the Mediterranean, rather than on the other side of the Atlantic?

Debates about the return of antiquities—not to mention the treasures of indigenous peoples—to their places of origin are often couched in legal and ethical arguments: were they obtained through legitimate and lawful means? is there a moral duty to return objects to cultural or ethnic groups that maintain a historical geographical connection to them? do these legal and ethical factors supersede the value that comes from them being publicly accessible in the museum that owns them? The claims made on archaeological materials in particular can often have nationalistic implications—the Elgin marbles “belong” to the Greek people as an inalienable part of their present-day identity, despite the huge discontinuities between the ancient Athens where they were made and the modern Greek nation state that now lays claim to them. Such approaches can sometimes feed into ethnocentricism, reinforcing divisions and giving support to the notion that culture and history can and should be laid claim to by national communities rather than made broadly available to all.

Yet on the other side of the coin is a genuinely liberational potential that heritage and tradition are able to unlock, especially for subordinated communities, in the face of the homogenising effects of imperialism and globalization.16 It is through the renewal of the past, as Bhabha suggests, that cultural production can truly innovate, interrupting “the performance of the present,”17 and making possible new ways of being in the world that can work against existing power structures. Ultimately, there are no easy answers to questions like these: the troubling imperial legacies of encyclopaedic museums must be balanced against the cosmopolitan and inclusive ideals they embody; the claims of ownership that contemporary peoples and nations make over museum collections must be considered with some awareness of their tendency towards more limited understandings of who culture belongs to. Neither the universalising tendency of the encyclopaedic museum nor the exclusionism of the nationalist or ethnocentric paradigm is without its flaws. 18 Who do antiquities belong to? Who ought they belong to? Is “ownership” even the right way to think about it?

In any case, as urgent as these issues may be, the ethics and legalities of museum collection practices are not a central focus of Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X). These problems are there in the background, but ultimately Hazewinkel directs us to pay attention to something that often gets passed over entirely in these debates. As such, his work constitutes a valuable contribution in its own right to urgent and ongoing discussions about museums and their roles in the twenty-first century. Whatever the legalities, whatever the ethics attending to the Met’s antiquities collections, Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X) reminds us that there is—inevitably and unavoidably—a loss associated with these objects’ display in a North American museum. Sunlight, breezes, rain, snowfall, dust, sea spray, birdsong, cicadas: these were a part of the lifeworld of these stone sculptures for so many centuries. But once they were unearthed and shipped off on their roundabout journeys to New York, this aspect of their materiality was lost forever. What is more, any meanings they might have come to hold within the cultural context of their original locale were stripped away.

Today on the gallery floor of the Met, these objects can lay claim to the attention of a huge and diverse audience, and they are carefully protected against the ravages of time by glass cabinets, watchful guards and a temperature-controlled climate. But these things have come at a price, and it is one that can never be repaid. They are never—never—going to find their way back to their homelands.

Endnotes

1. Originally published in the Wall Street Journal on December 12, 2002, the text has been reproduced in full in e.g. Ivan Karp et al., eds., Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 247–9.

2. Jeanette Greenfield, The Return of Cultural Treasures, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007 [1989]) is a foundational discussion of the issues surrounding repatriation of cultural property.

3. See Donatien Grau, “Introduction: The Encyclopedic Museum: A Catchphrase, a Concept, a History,” in Under Discussion: The Encyclopedic Museum, ed. Donatien Grau (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2021), pp. 4–6 for a concise discussion of the different histories and meanings of these two ways of labelling these institutions.

4. James Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity?: Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 140.

5. See Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity? and Museums Matter: In Praise of the Encyclopedic Museum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). Cf. also Neil McGregor, “The whole world in our hands,” The Guardian (Review Section), Saturday 24th July 2004 <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jul/24/heritage.art>

6. E.g. Mark O’Neill, “Enlightenment museums: universal or merely global?” Museum and Society 2.3 (2004): pp. 190–202, Geoffrey Robertson, Who Owns History: Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure (London: Biteback, 2019).

7. Grau, “Introduction,” p. 7.

8. This was very much the main axis of debate for some years after the Declaration: see e.g. John Henry Merryman, ed., Imperialism, Art and Restitution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), Lyndel V. Prott, ed., Witnesses to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects (Paris: UNESCO, 2009).

9. See now Donatien Grau, ed., Under Discussion: The Encyclopedic Museum (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2021).

10. See the RISD Museum’s online publication Raid the Icebox Now <https://publications.risdmuseum.org/raid-icebox-now>.

11. Alongside artistically-led interventions like those that comprise Raid the Icebox Now, we might add broad efforts at rethinking how and together with what kinds of information museums display their permanent collections in order to foreground some of the troubling dimensions of the recent histories of their objects, which are now occurring at institutions across the world, as well a number of recent geographical grounded survey shows at major institutions that explicitly draw attention to the imperial violence that lies in the background of the objects on display, like Kongo: Power and Majesty (2015) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Ancient Nubia Now (2019) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

12. On which, see especially Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2009).

13. Not to mention they are now very often carried out at the direction of or at least in collaboration with the institution that is the object of the critique: as Andrea Fraser recognised already a decade and a half ago, institutional critique has itself, paradoxically, become institutionalised as museums and galleries regularly encourage contemporary artists to engage critically with their sponsoring institutions (“From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” Artforum 44.1 (September 2005): pp. 100–106).

14. A trend influentially identified by Dieter Roelstraete, “The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art,” e-flux journal 4 (2009), and elaborated in his 2014 exhibition The Way of the Shovel at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the associated publication The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2014). In the years since, the archaeological has become an important and increasingly explicit focus of curatorial activity, especially in places with rich local archaeological heritage. In 2017, the fourteenth iteration of the major art quinquennial documenta 14 was held, for the first time, not only in its traditional home of Kassel, Germany, but also in Athens, Greece, having as its theme Learning from Athens, and focussing to a significant degree on the possibilities that the city’s archaeological past (and its present relationship to that past) offers as a resource for contemporary art: see Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk, eds., The documenta 14 Reader (Munich: Prestel, 2017), and also Brooke Holmes and Karen Marta, eds., Liquid Antiquity (Athens: Deste Foundation, 2017). Over the last decade the non-profit NEON, funded by businessman and collector Dimitris Daskalopoulos, has been producing major contemporary art exhibitions in Greece, as often staged in archaeological sites and museums as in more traditional contemporary art venues. In Italy, the new government-sponsored Pompeii Commitment (2020– ) seeks to activate that archaeological site through an extensive programme of exhibitions, commissions and collecting in contemporary art. Cf. now also on this tendency David Joselit, Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020).

15. A whole series of questions attend the relationship between original and copy, and arise constantly when we are considering ancient Greek statuary in particular, where the history of reproduction extends for two-and-a-half millennia, and much of our understanding of style and output of the famous sculptors of antiquity is today only accessible though copies of their work made already in the ancient world. Fondazione Prada’s 2015 exhibitions Serial Classic in Milan and Portable Classic in Venice, together with the accompanying publication, Salvatore Settis, Anna Anguissola and Davide Gasparotto, eds., Serial/Portable Classic: The Greek Canon and its Mutation (Milan: Progetto Prada Arte, 2015), provide some valuable reflection on issues of originality and reproduction as they relate to ancient Greek statuary from a curatorial and art historical perspective.

16. Cf. Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), and within the specific context of contemporary art, Joselit, Heritage and Debt.

17. Bhabha, Location of Culture, p. 10.

18. Joselit’s very recent analysis of the landscape of global contemporary art in Heritage and Debt brings into relief the recurrent tension between cosmopolitan and nationalist impulses in contemporary artistic production that is grounded in heritage.