AH

Hazewinkel's artist notes Displacements I-X are followed by Johnstons essay Presence Elsewhere

Download the exhibition catalouge Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (Displacements I-X) here

ARTIST NOTES

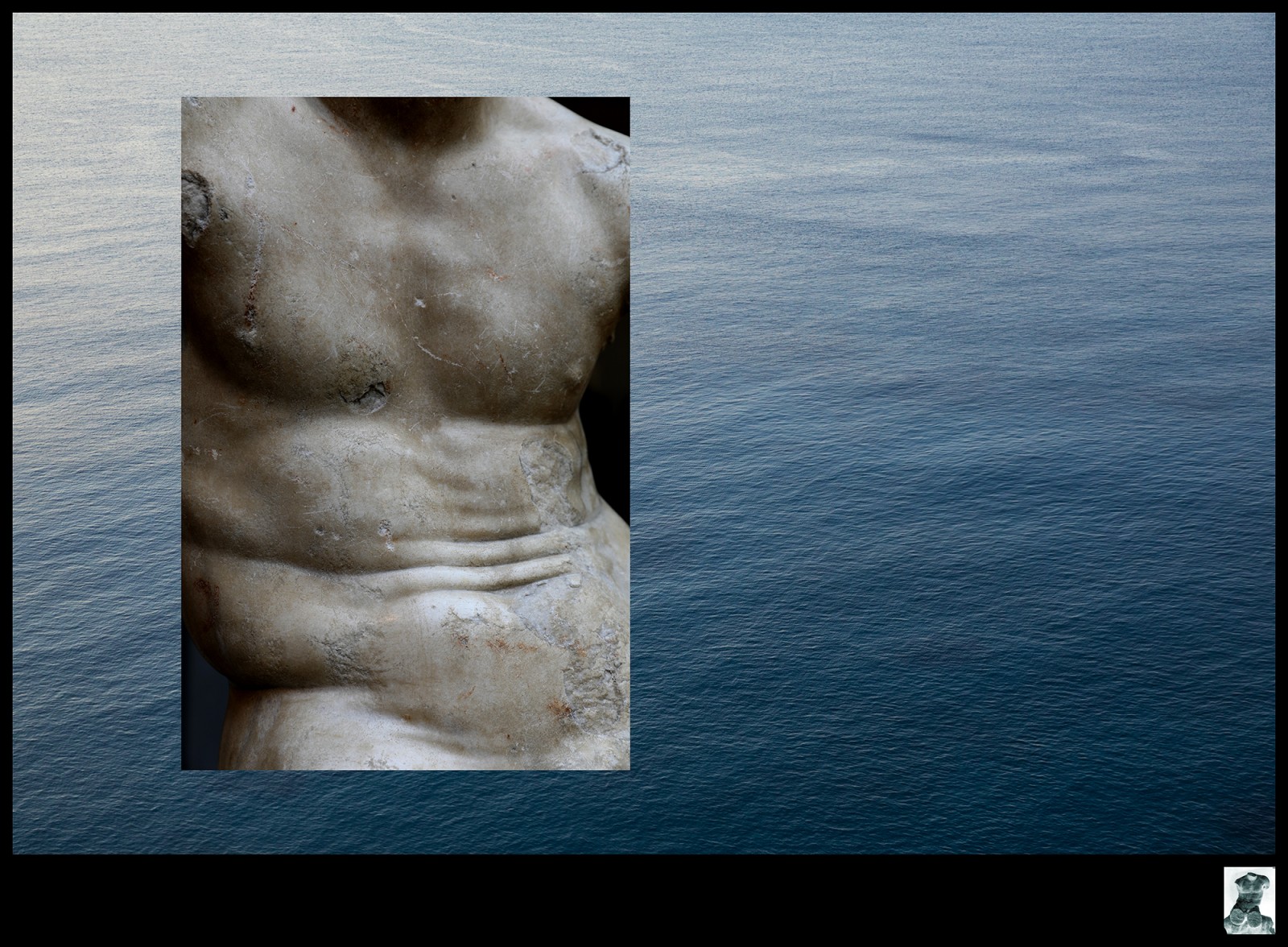

DISPLACEMENT I

It is easy to think of stone as cold, but marble is a stone that quickly takes the warmth of the sun and if we consider that many ancient statues stood about in the landscape, their bodies become softer, somehow more alive in our minds.

Time is of the essence in this photograph, which is the first of ten that I have been developing for about a decade. Here however, the meaning of that stale cliché is flipped, rather than urging the need to make haste, in this context the opposite is true. The time taken to make this work has somehow seeped into it, becoming a part of it. There is a lot of waiting in this work, which evokes among other sensations, the exquisite deep stillness that comes with being forgotten and the exuberance that comes with resurfacing.

Geological time, archaeological time, deep time, oceanic time, good times, bad times, and (to bring it back to the camera), exposure times mingle with the limbo of the photographic archive and the temporal mash-ups of encyclopaedic museum displays, generating the pulse of this work.

In the lower right margin is a small image of a digitised gelatin dry-plate negative (c.1910) sourced from a photographic archive in Rome. It represents the badly damaged torso of a young Herakles that was made in 360 BCE. A disquieting sense of serene brutality emerges at the breaks where the legs, arms and head once joined this torso. The breaks appear to be intentional but we can’t be certain, early Christian brutalisation of ancient statues, and the related desecration of pre Christian temples and sanctuaries is not always easy to identify. The archival image represents one of nine large glass plates (each measuring 39.5 x 29.7 cm) that depict the broken figure from different perspectives. They were made to encourage the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York City to acquire the torso in the period during which new-world institutions scrambled for old-world cultural legitimacy, which was itself an exertion of power with roots in imperialist strategies. The archival image is paired with a larger image, of the same torso, that I captured in available light in the galleries at the Met in 2017.

These images spill out into the light reflecting off an open, wind ruffled sea not far from Athens, which is where this young Herakles was created some 2300 years earlier.

This sets me thinking about the special bond between materiality of things and place and of homecomings, of all kinds, as it reminds me of the exquisite sensation of cool air rushing into my lungs after swimming underwater for as long and far as possible.

DISPLACEMENT II

Colours, like stones, journey though the Lifeworld, typically setting out as minerals or pigments. In archaic times Black Sea Cinnabar rendered bright reds, Orpiment from Ephesos offered golden yellows, Lazurite from Afghanistan provided deep blues, while Chrysocolla from Attica furnished a forest of greens. Colour in the ancient world, more than today, sent the beholder on imagined journeys. In ways not dissimilar to the songlines of ancient Australia, colour-paths may have functioned as a kind of chromatic compass aiding journeyers on their own paths through the lifeworld.

Commonly held perceptions fuel the idea that the marble bodies of antiquity gleamed whitely and brightly in the shadowy ancient world. That conception looms large in our contemporary collective imagination, but it is a misconception, a material misunderstanding of antiquity with threatening contemporary social legacies.

Previously unnoticed or simply ignored pigment traces identified on the broken bodies of antiquity have recently become a focus of archaeological scholarship. These colour residues provide data that proves that much archaic and classical sculpture (and architecture) was brightly painted. To some contemporary imaginations, visions of a brightly coloured ancient world may seem lurid, loud, even distasteful or garish, but brightly coloured it was.

As well as challenging our visual imaginings of antiquity, these delicate chromatic residues help debunk violent ideologies put forth by white supremacists in their misguided legitimising claims of being connected, genealogically, to the whiteness of classical antiquity.

Colour trace research is doing more than recasting how we imagine the remote past, it is also contributing to the swelling corpus of research which, in various ways, supports the important work of decolonising museum collections, especially those collections that are founded on imperial thinking and activity.

This body of photographic work does not confront those issues head on rather it approaches them obliquely. It aims to draw to attention to an intimate sensorial, personal dimension to, and the ongoing collective cultural consequences of a museologically stimulated amnesia toward cultural plunder. In this way it signals what might be considered a persistent wounding.

In the lower margin of this photograph is a digitised image of a dry-plate photographic negative (c.1905) sourced from the John Marshall Photographic Collection, which is held at the British School at Rome (BSR). This idiosyncratic collection is comprised of images created principally as aids to the late 19th and early 20th century commercial apparatus associated with the often-dubious sale of cultural artefacts to universal museums.

Here the subject is a once brightly painted late 6th century BCE marble representation of a young woman, a kore, said to have been found on the island of Paros. Elegantly attired in a style originating in the Greek coastal cities of Asia Minor, this young woman pulls her linen tunic tightly across her legs as her cropped cloak cascades in layered folds to her waist. I photographed her as if under a spell I was following her through the galleries at the Met, where to me she appeared to be cutting a path to the nearest exit.

The cave like formations of the rocky landscape recall the need for shelter and earthy activities, perhaps the search for minerals, to be ground into pigments to personalise objects of everyday use.

This young woman powerfully holds her ground; she seems to know where she is headed, perhaps more clearly than we do.

DISPLACEMENT III

Seafarers will tell you that the horizon is roughly 22 km distant (about 12 nautical miles). This is true if you are standing on the deck of a ship, but if you are sitting in a life raft, or on a surfboard, the horizon is about 4.5 km away. Horizons are set by the distance that separates our eyes from sea level. This handy formula helps to work it out – square root (height above surface / 0.5736) = distance to horizon.

A close friend once said to me ‘it’s always better to be just below the horizon, that way people can sense your emergence but can’t focus on you as a target’.

The altitude of the landscape in this photograph is roughly 700m above sea level, so its horizon is roughly 122 km away, which here is half way to the Libyan coast. Considering the fixed gaze of this remarkable marble portrait (c.130 CE), and what we know about whom it represents, sets us thinking about what, in this context, she may be sensing.

Meet Marciana, the elder sister of the Roman Emperor Trajan. Trajan’s reign (98-117 CE) is best known for territorial expansion, public building works and the development of social welfare policies, most notably the alimenta which saw the use of public funds, generated by estate taxes, to support orphans and poor children. Marciana and Trajan were close. Marciana had one child, a daughter named Salonina Matidia. Trajan, although married, remained childless. Following the death of her husband, Marciana and her daughter lived with Trajan and his wife. Marciana and Trajan often travelled together on campaigns; she had his ear and assisted him in important decision making. Marciana was a powerful person, perhaps more in the human sense than the political, or perhaps equally in both.

When I think about Trajan’s achievements, and how the male dominated recording of history brings them down to us, I can’t help but wonder whether his social welfare ideas were actually her ideas, or perhaps their shared ideas, which surfaced in sea gazing conversations about love and care and roles within families and the importance of multifarious family forms.

Unlike the position of this life-sized portrait in the light filled yet airless galleries of the Met, here Marciana gazes across the Libyan Sea toward the horizon. This photograph’s archival source is a gelatin silver print drawn from the John Marshall Photographic Collection in Rome, which I have drawn upon for this entire body of work. In it Marciana wears an elaborate hairstyle, however with my portrait of Marciana I am more interested in the precise engraving of her eyes, which to my mind are a way in to knowing her.

As with all good portraits, this portrait of Marciana leaves you with a sense of embodied mutuality, the sense that you somehow know, or better, share something with the subject. And it is precisely this fragile hard to pin down sense of connection with others that keeps us all connected, especially in times of difficulty.

With this Journey in the Lifeworld of Stones those of us that have ever gazed out to sea, at uncertain personal horizons, may sense the ongoing spirit and support of a woman long gone.

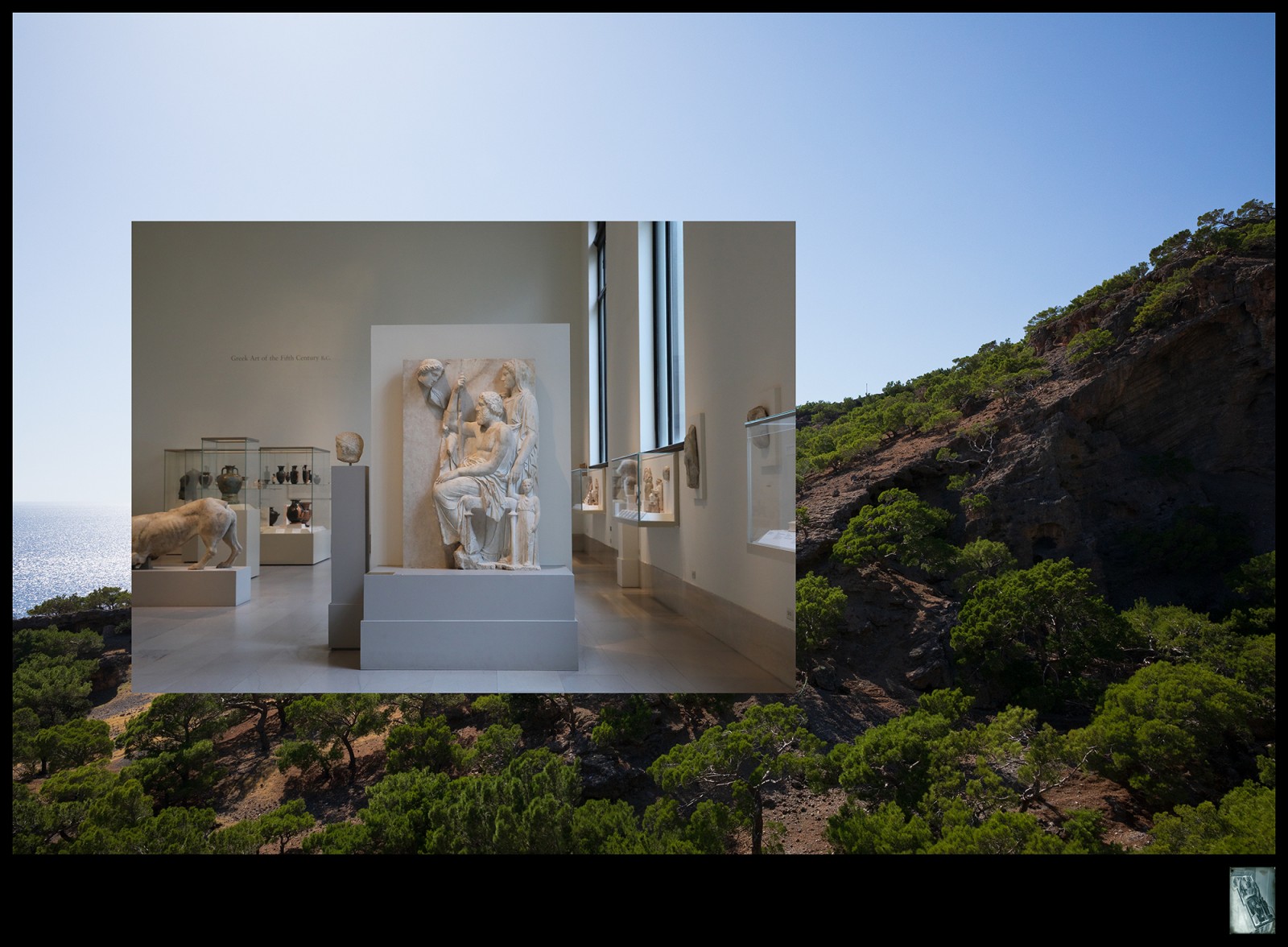

DISPLACEMENT IV

During the ten years that this body of work has been in development the working title of this photograph has been A Family Group. That fit neatly with my evolving understanding of the role of family in contemporary and ancient Greek societies, and on a more visceral level, when thinking about my own family, my at times times prickly place within it, and how together we have navigated profound loss. The grave-marker at the centre of this work reminds me of the inescapable archaic timelessness of grieving.

The inscriptions that once accompanied this grave-marker are missing, much of this family’s story remains unknown. To be honest we can’t be certain who is mourning whom here. Are the seated and veiled figures parents mourning their daughter? Or is she mourning her father, or her mother, or both? An intense solemnity and profound sadness reaches us through this uncertainty, what touches us is the ache of loss.

In the lower right margin of this photograph is a digitised reproduction of a gelatin dry-plate negative (c.1911) rescued from the temporal limbo an archive of images that were generated to support the sale of ancient objects to new-world museums; an activity that displaced the objects from the sensorial meanings of their original spatial, material and cultural contexts. In it we see the gravestone of a family group that has been removed from a cemetery and is ready to be trafficked. Acquired by the Met in 1911 from G.Yanacopoulos (a dealer of antiquities based in Paris), this late classical stele (c. 360 BCE) was originally set up by a family from Attica, under the Attic sky. It is made of Pentellic marble, which is cut from the earth of Attica. Mt Penteli, on the NE outskirts of contemporary Athens still functions as a marble quarry.

For me there is a special materially triggered togetherness at play here, a form of material semiosis, wherein our capacity for an embodied sensorial knowing emerges from the mingled awareness that this family and the stone that marked the end of their lives are of the same place, or better, that they are the same place, they are autochthonic. This is where the word displacement, common to the titles of all the photographs in this series, really starts to hum, prompting a cascade of questions concerning the contemporary function and relevance of encyclopaedic (or universal) museums. What meaning can be made in an experience of this grave-marker in the tourist filled galleries of the Met? What social tensions emerge from such hermetic heterocosms? What knowing might be lost in displacement?

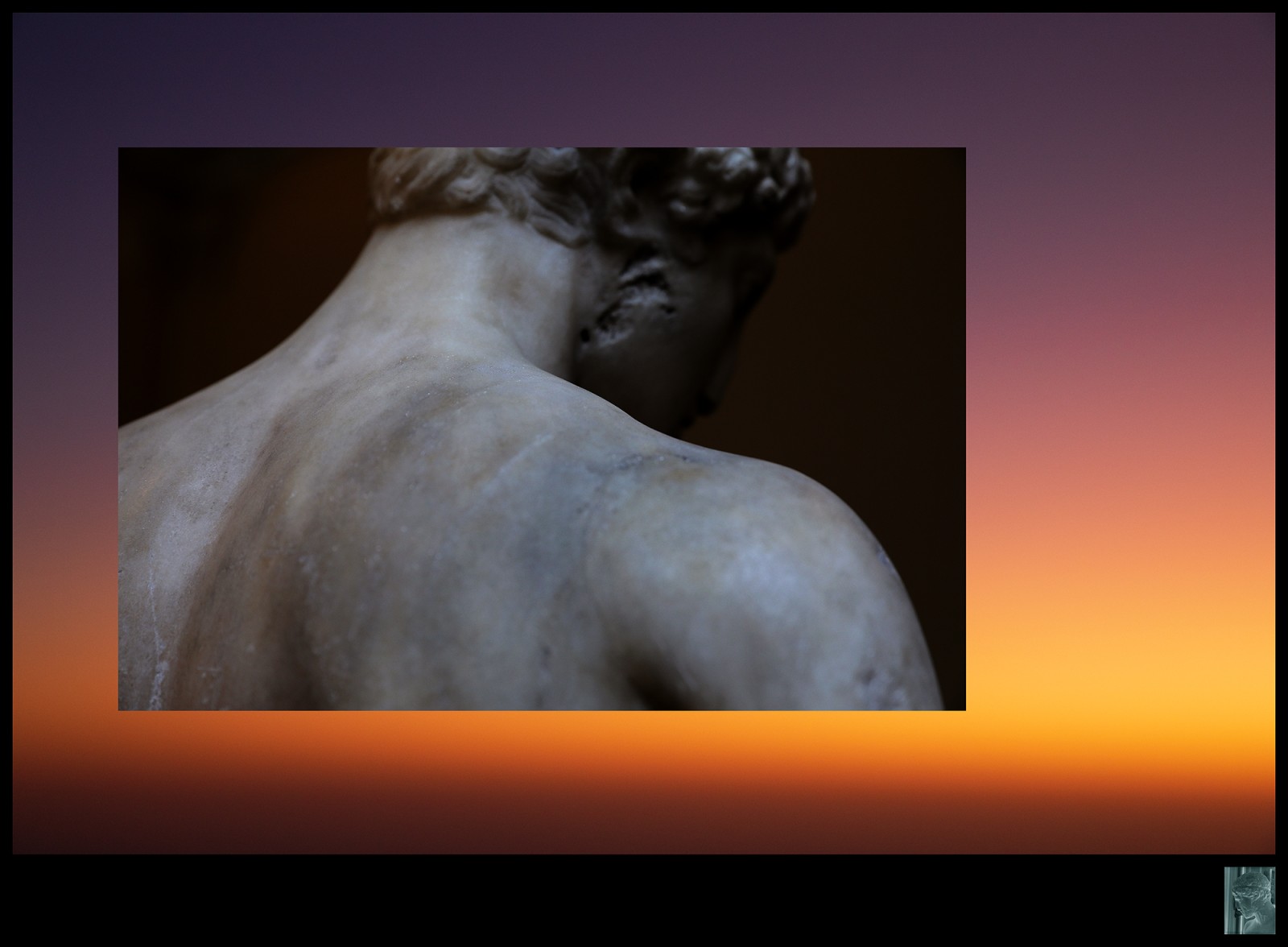

DISPLACEMENT V

Walking backward through the word paradox (with a sight line borrowed from the Māori whakataukī - or proverb - Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua, which can be translated as I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past), we arrive at the Greek para meaning ‘contrary to’ and doxa meaning ‘opinion’; doxa has further links that extend back to dokein which means ‘to appear, to seem, to think’.

The central image of this photograph teems with paradox contextualised within an atmosphere of uncertainty. The setting could be the beginning or end of any day - dawn or dusk, sunrise or sunset. Without knowing where I captured this image you can’t be sure. The uncertainty is intentional, it aspires to fruitfulness.

Borrowing another perspective (this time from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle), we learn that the closer we examine the momentum of nature’s smallest particles (quantum particles) the less we can know of their location and vice versa. This sheds light on a particular fuzziness essential to the very nature of nature.

Here stone is tender. The intimacy between a young girl and her birds is not just academically symbolic, it is soul stirring and elevating. Anthropocentrism is alien to children. Here creatures of land and sky merge (formally and conceptually), feeding one another love, trust and tenderness. In this intimate moment, fixed in stone, nothing else exists in their fuzzy shared world except their exquisite exchange which is witnessed by a memory in the shape of a fragmented bird.

This is the grave stele of girl who died young, perhaps only 8 or 9 years old. It was made circa 450-440 BCE of Parian marble, a local stone, known for its fine-grained whiteness and its light capturing qualities. Standing at 80 cm we might imagine this stele as a mirror reflecting Dovegirl (as I have always called her) at her death. It was discovered on the Greek island of Paros in 1785 and was promptly shipped to the Isle of Wight (UK) where it became a possession of Sir Richard Worsley of Appuldurcombe House. In the early 1800’s its ownership was transferred to the Earls of Yarborough at Brockelsby Park Lincolnshire (UK) where for the next 100 years or so successive Earls of Yarborough called her theirs. In 1927 under advice of the antiquities agent John Marshall, the Met acquired her. The acquisition process was supported by photographic prints made from the gelatin dry-plate negative represented in this photograph’s lower right margin.

All of this ownership and transference has at it essence the act of taking - taking away, taking advantage, taking possession, the list goes on...running counter to the exquisite exchange represented.

There is another image reproduced here, it represents a plaster copy of Dovegirl’s stele as it stands today in the sunlit courtyard of the small overlooked Archaeological Museum of Paros. If you find yourself on Paros, pay her a visit, take a moment to look into the sky and enjoy the abundant birdsong.

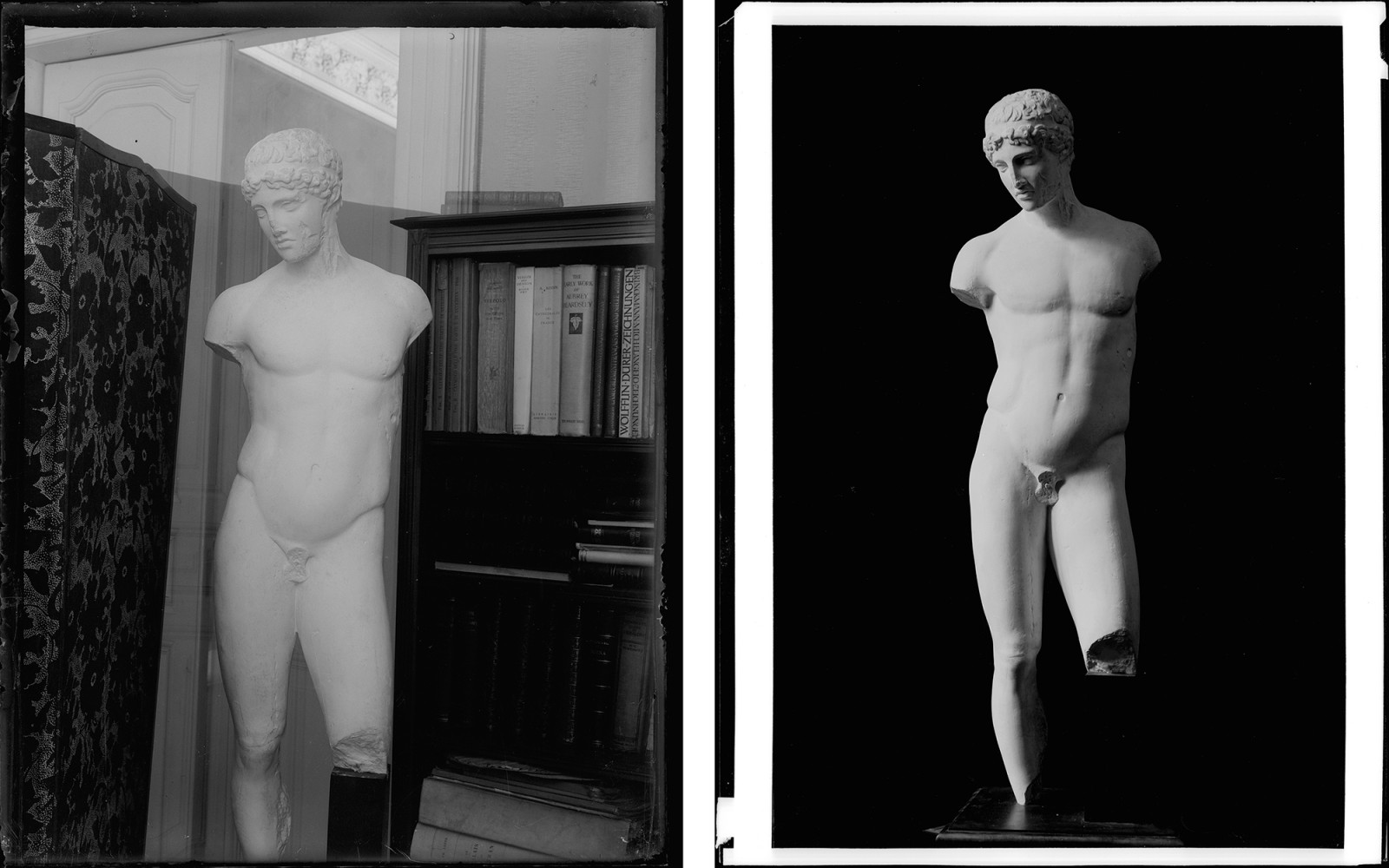

DISPLACEMENT VI

The climate controlled world of photographic archives prioritises the information carrier, which, in that specific context, means the material that supports the image in either negative or positive states. While a photographic archive’s technical facility prioritises the materiality of photographic artefacts the most engaging conversations that I have with archivists, revolve around the image itself and how the image might be reimagined.

The archival material at the inception of this body of work is drawn from the little known John Marshall Photographic Collection, which is held at the BSR. The collection is modest in scale comprising approximately 2500 gelatin silver prints and roughly 800 gelatin dry-plate negatives. The principle subject of these commissioned and collected photographs is Greek and Roman sculpture.

John Marshall (1862-1928) was a highly esteemed scholar of Greco-Roman sculpture and a dealer of antiquities. During the period in which he worked, his problematic dual role is likely to have appeared less two-faced than it does today. From 1906-1928 he was the exclusive European agent for antiquities to the recently established Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The glass negative reproduced in the lower margin of this photograph is one of eleven involved in the Met’s 1926 acquisition of the subject of this photograph’s central image. A 1st century CE Roman marble copy of 5th century BCE Greek bronze original.

Seven of the eleven archival images representing the naked male figure appear to be photographed in Marshall’s domestic setting providing us a rare tantalising glimpse into his personal life. The other four, bearing homoerotic and stylistic connections with much later works by Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989) and Bruce Weber (b.1946), were created in 1926 by the Roman photographer Cesare Faraglia under controlled studio lighting conditions.

For me, the temporal distance between the making of Greek bronze and its Roman marble copy is occupied by questions that revolve around the motivations for making art objects and the social, political and cultural implications of the places they are made for. The original bronze was created to commemorate a young man’s victory at games; it mostly likely stood outdoors amongst trees in a sanctuary. The Roman version was made to satisfy the emergent Imperial thirst for sensual objects to decorate their bathhouses and the villas of the wealthy.

So why did I make this photograph? I made it for Marshall who, through my sustained engagement with the images that he collected and commissioned, I feel like I have got to know. We are both gay men and I suspect we would have got along. However his life was lived at a time when our sexuality required codification, his archive can be read as an entanglement of that, and although I don’t agree with his museological politics, I understand and celebrate his desires.

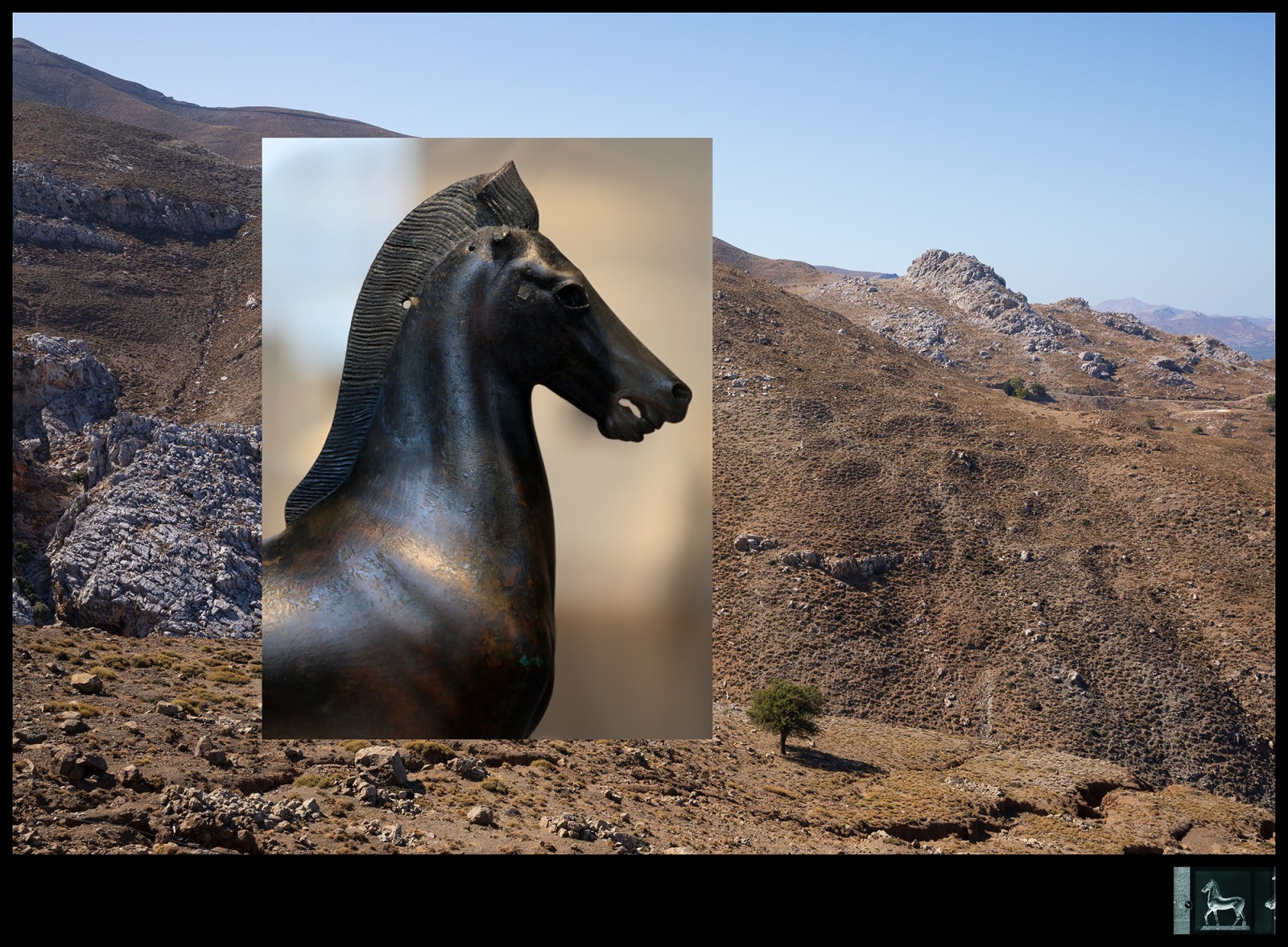

DISPLACEMENT VII

When they saw that Patroklos had been slain,

that one so strong, so young and so valiant,

Achilles’ horses began to weep;

their immortal spirits enraged

to witness the handiwork of death.

They reared their heads and shook their manes,

scarred the earth with their hooves, and mourned

Patroklos, rendered lifeless, gone,

now useless flesh, his soul no more,

defenseless, never more to breathe,

cast out of life into nothingness.

Zeus saw the immortal horses weep,

and was moved. “I acted thoughtlessly

at Peleus’ wedding”, he said,

“better we had never given you as a gift,

unhappy horses! What business did you have there

amid the wretched human race, fate’s diversion?

You who will never die, will never age,

only fleeting woes may plague you. Men, though,

have drawn you into their own miseries”.

And yet it was for death’s eternal woes

that those immortal horses shed their tears.

The Horses of Achilles

Constantine P. Cavafy

C.P. Cavafy: The Canon. The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems, trans. Stratis Haviaras, Athens: Hermes Publishing, 2004. 33. Reproduced courtesy of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, University of Harvard.

DISPLACEMENT VIII

Again we stand together before death, or more accurately, before a marker of a life lived, that brightly burned and early ended. Some scholars say that this is the most intact grave-marker of its type to have survived the 2550 years since it was created, in the period we now call Archaic.

There are many remarkable things about this object, for example it is a little more than 4m in height, but what captures my imagination is that the inscription on its base is composed from the personified perspective of the stone itself. Here stone has voice and it speaks with the intimacy of someone close to the family that this young man, Megakles, was a part of.

“to dear Me(gakles), on his death, his father and dear mother set me up as a monument.”

Having voice and being heard is an important aspect of being a part of and contributing to something (like a family), but in the parlance of separation, or diaspora (from the Greek diaspeirein: dia - across, speirein- scatter) that dislocated being a part of something is sometimes most eloquently expressed through present absence, and silence.

I am more apart from my family than not, and recently I’ve come to appreciate that that is my part in my family (which has diasporic origins). Much of contemporary society is diasporic, increasingly the movement of people comes in floods, even as nation-state borders become increasingly brutal, and inhumane. And so, we collectively become increasingly dependant upon threaded stories of connection, scattered rhythms, poetry and tastes, dances and rituals, of the perfumes of plants and family members we may never have known, and their experiences that have been transferred to us (often in the form of objects) that inhabit and shape our memories.

Megakles’ stele is indeed a remarkable object and its journey in the lifeworld is one of scattering, of being purchased, traded, bartered, freighted. As it stands today at the Met it is an assembly of fragments acquired by various means over 40 years (1911-1951), which is more than twice the number of years that Megakles lived under the Attic sky. Today his material afterlife exists in bits and pieces in various museums and galleries in different cities around the world. His right forearm is in a museum in Athens (I recently went looking for it, to no avail), the head of his younger companion (presumably his little sister), is somewhere in Berlin while the 5 fragments reassembled in this photograph stand beside the flooding traffic of 5th Avenue.

DISPLACEMENT IX

The draped figure in this photograph is Eirene the personification of peace. While her right leg is slightly advanced she appears powerfully set, she holds her ground. Unusually, we know precisely the year that this Eirene was made, 375 BCE. We know this because of its sudden appearance on some relatively recently excavated painted vessels and because Pausanias, the 2nd century Greek writer, describes seeing it in the ancient Agora at Athens.

My point of departure is different. I’m setting out from this personification of peace into the age-old battle for authority between images and words, which in the age of fake news and Photoshop assumes different perspectives and relevance.

The following story is rooted in conceptions of union between two Olympian heavy hitters, Hera and Zeus. Then it descends into a more bloody battle between Hermes and Argus, which, allegorically speaking may be considered as the conflict between words/language/communication (the purview of Hermes) and sight/vision (the purview of Argus).

The players:

Hera: wife of Zeus, mother of his legitimate children, known for jealously and rage.

Zeus: husband of Hera, lover of many others, represents authority based on power, is considered a projection of law and justice.

Io: one of Zeus’ many lovers (Antiope, Callisto, Danae, Leda, Semele and Maia are others). Io represents disguise and submissive acceptance.

Hermes: accepted illegitimate son of Zeus, represents language, words and communication.

Argus: the 100-eyed giant represents sight, surveillance and uninterrupted vision.

The plot:

Hera learns of Zeus’ love for Io and flies into a jealous rage. To protect Io from Hera’s wrath, Zeus transforms Io into a radiant white heifer. Suspicious of her husband’s transformational proclivities, Hera sends in Argus to keep a close eye (or 100), on Io. In response Zeus deploys his son Hermes, as assassin, to kill Argus. Io flees the messy scene and little attention is further payed to her. But that is not the end of it. Hera makes one more (kind of creepy) gesture. She removes from dead Argus his multi eyed skin and drapes it upon the body of her favourite bird, the flightless peacock, which comes down to us as symbolic of the decorative rather than the meaningful.

The power of images and power of words are not the only themes central to this story, sound is also present, and it too reverberates with vestiges of the combative. Soaring in violent triumph Hermes (metaphorically) flies through our skies lyrically playing his lyre while the ground bound decorative bird squawks its inharmonious song. In this way the defeat of images by words is ongoing, it is perpetual, or as Michel Serres puts it “sight gazes without seeing at a world from which information has already fled.”

Make peace, personify it, we need it.

M. Serres, The Five Senses. A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. Translated by Peter Cowley and Mararet Sankey. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2008. p 51

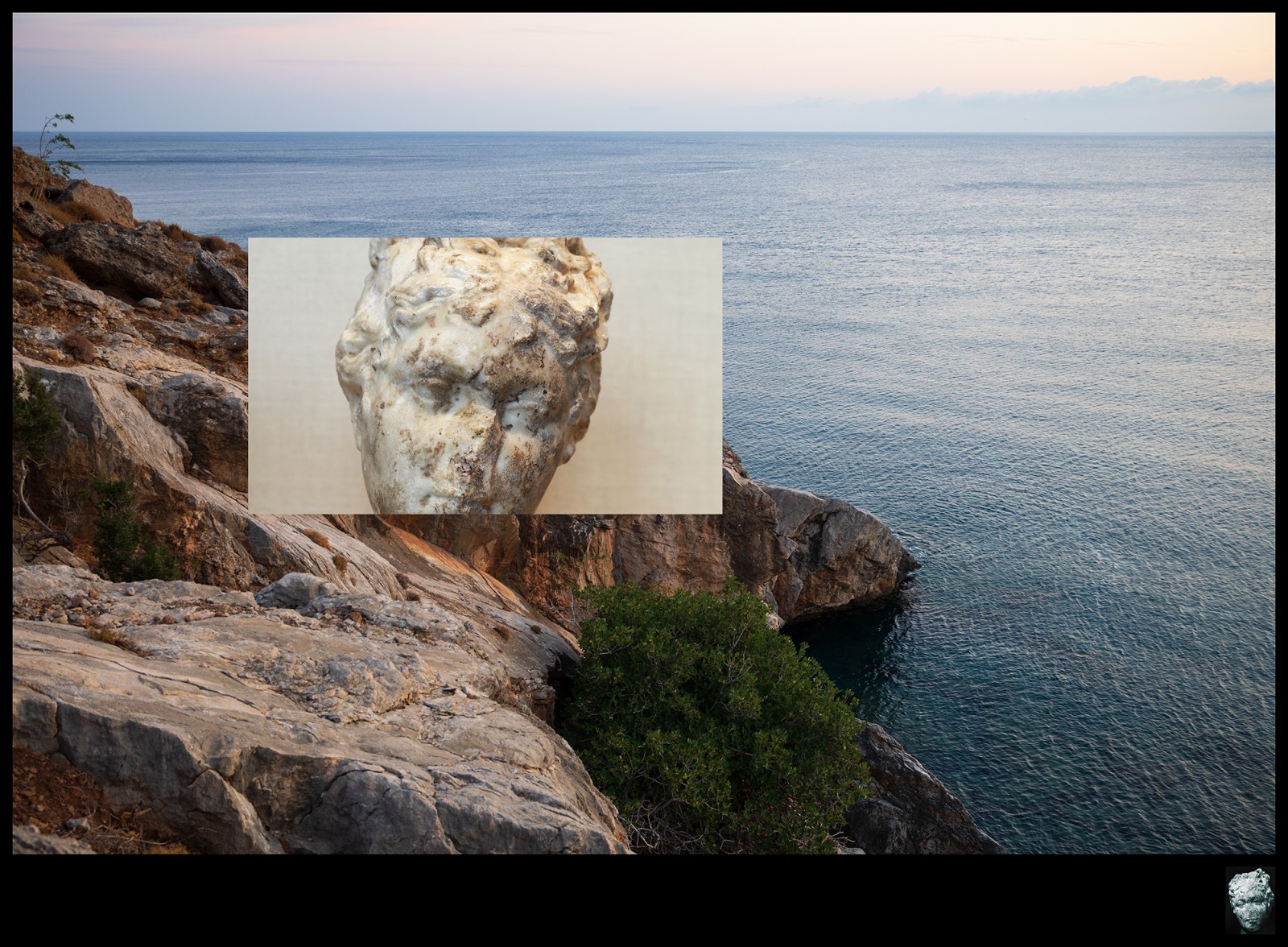

DISPLACEMENT X

The material subject of this work is a human-scaled marble head of a young girl, which has, at some time since it was made (between 100 BCE and 100 CE), been removed from its body.

The archival impetus for this work is a small (10.5 x 8cm) gelatin silver print that I discovered in a solander box titled ‘Suspicious - Forgeries’ in the John Marshall Photographic Collection at the BSR. The head was acquired by the Met in 1926, last time I checked there was no provenance associated with it listed on their website.

In this photograph there is a sense that the young girl is peering through the back of the landscape image into a world that is familiar to her. It is as if she is checking to see if it is safe to re enter the beloved space that she remains inextricably a part of.

Pulsing through all the works in this series are cadences of encyclopaedic museum dread that call for greater institutional accountability in relation to the slow, ongoing, cultural violence that some museum collections continue to exert. Issues associated with this are debated in many languages - political, legal, scholarly and poetic (to name a few), these photographic Journeys In The Lifeworld of Stones (displacements) aim to highlight, participate and contribute to that discourse through a different language. It is seems appropriate then to arrive at displacement number X of X in a territory bounded by two languages between which you can further understand what I have tried to do in my own language.

From ‘A long Duration of Losses’ by Felwine Sarr and Bénédict Savoy ‘the extraction and deprivation of cultural heritage and cultural property not only concerns the generation who participates in the plundering as well as those who must suffer through this extraction. It becomes inscribed throughout the long duration of societies, conditioning the flourishing of certain societies while simultaneously continuing to weaken others’.

And again from Cavafy

Although we destroyed their statues

and ran the gods out of the temples,

that doesn’t at all mean that they’ve died.

O land of Ionia, they still love you,

they still hold you dear in their souls.

When the August dawn washes over you

the vigor of their lives enters the air itself.

And on occasion an ethereal young figure,

difficult to discern clearly, passes over

your hillcrests, a swiftness in its stride.

Ionic

Constantine P. Cavafy

A Long Duration of Losses is drawn from the 2018 report by Senegalese economist F.Sarr and French art historian B.Savoy titled The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Towards a New Relational Ethics commissioned by the President of the French Republic Emanuel Macron for the Ministère de la Culture Republique Française. The quotation can be found on page 8

C.P. Cavafy: The Canon. The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems, trans. Stratis Haviaras, Athens: Hermes Publishing, 2004. 62. Reproduced courtesy of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, University of Harvard.

PRESENCE ELSEWHERE

In 2002, the directors of eighteen of the most important art museums in Europe and the United States signed onto a now-infamous “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” a brief but vigorous defence of institutions—like most of their own—“whose collections are diverse and multifaceted.” 1 This intervention was motivated by increasing calls for the repatriation of items in the collections of Western museums that were obtained, usually long ago, through illicit and poorly documented means, including theft, looting and smuggling. 2 In making its case, the Declaration suggests that by placing objects in “direct proximity to products of other great civilizations,” these “universal” museums bring into relief the distinctive characteristics of different cultural traditions as well as the sheer variety of human experience. Accordingly, to narrow their collections through repatriation would constitute a “disservice to all visitors.” The Declaration’s arguments rest on some troubling assumptions and oversights, not least the incongruity between their claim that universal museums make material “widely available to an international public” and the near-total geographical concentration of such institutions in Europe and North America.

In the decades since, “universal” or “encyclopaedic” museums 3—those that “comprise collections meant to represent the world’s diversity, and … organize and classify that diversity for ready, public access” 4 —have come under increasing scrutiny. They have found their defenders, most prominently James Cuno, now President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust and formerly the director of a number of major American museums, who has advanced arguments, ultimately grounded in Enlightenment values, that the encyclopaedic museum presents a valuable vision of human culture and history as a universal inheritance available to all, freed from the parochial and ethnocentric claims upon heritage made by modern nation states.5 They have also found their fair share of detractors, who have tended to emphasize how the collections of these institutions are deeply implicated in vast historical power imbalances, in particular those produced by Western imperialism, between the places where the museums are located and the places where much of their collections originated from.6 Moreover, these aspects of their institutional histories have usually been left entirely unacknowledged and uninterrogated within the museums’ public displays. It is undeniable that the world’s universal museums—concentrated in North American and European states with ugly histories of colonialism, militarism, exploitation and empire—obey the logic of imperialism, seeming to imply that the creation and dissemination of knowledge can be centralized and universalized, and moreover that the politically, culturally and militarily powerful nations of the West possess a unique right to catalogue and control the narratives that we tell about the world and the past. These institutions are “products of empires, whose genesis was inherently culpable, as they did not have the moral right to tell a narrative of the world to the world.”7

Recent academic debate about universal museums has moved on from a myopic focus on repatriation,8 and more nuanced perspectives have explored the serious problems inherent in the histories and cultural politics of these institutions even as they also acknowledge the merits of museums that allow for an appreciation of the world’s cultural and historical diversity and enable the recognition of connections between different cultures, geographies and temporalities.9 The question is no longer simply whether institutions can or should atone for their imperial histories by repatriating objects—an important issue to be sure, but only a small piece of the overall puzzle—but also how they might find other ways to expose the troubling aspects of their pasts across all dimensions of their operations.

Interest in the universal museum as a site of reflection is not confined to the discussions of academics, museum directors and other heritage professionals, but has recently become a recurrent focus of activity in contemporary art making and associated curatorial practice. Curators are intervening in traditional museum spaces to rethink how their legacy collections might be re-presented and recontextualised in ways that allow for new kinds of dialogue with perspectives outside of the dominant Eurocentric paradigm, frequently in close collaboration with contemporary artists. Characteristic is Raid the Icebox Now (2019–21), a curatorial project at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, inspired by Raid the Icebox (1969), an influential exhibition at the institution put together by Andy Warhol using selections from its collections store, and one of the earliest and most influential artist-curated exhibitions at a major museum.10 The legacy of Warhol’s project has now inspired a series of artist-led interventions in the RISD Museum’s galleries that interrogate the institution’s collections. This includes, for example, Simone Leigh’s The Chorus (2019), where the artist installed her own sculptures and some selections from the collections store amidst the existing displays in the museum’s Greek, Roman and Egyptian antiquities galleries, accompanied by a sound recording of texts written by women of colour. Leigh’s intervention explored continuities in artistic expression across time and culture and, just as importantly, interrogated the ongoing legacies and contemporary resonances of the cultural imperialism embodied by the archaeological objects on display.

Raid the Icebox Now, along with similar recent artistic and curatorial engagements with the politics of museums, their collections and their institutional histories,11 extends out of “institutional critique” as a major thematic of contemporary art since the 1960s,12 now shaded by the important discussions about the imperialist histories of major museums that have developed since the turn of the millennium.13 Related is a trend in recent decades towards the historical and archaeological as an object of sustained interest in the work of many major contemporary artists and in associated curatorial practice.14 Andrew Hazewinkel’s Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X) can be understood within this context as a potent theoretical reflection on the limitations of the encyclopaedic museum as a space for the display of archaeological material, and the lingering effects of the violent acts of looting and smuggling that allowed for the assembly of these institutions’ collections. The artist’s materially- and experientially-grounded perspective puts the spotlight on a very particular kind of absence that attends archaeological objects held in museums, namely the loss of the highly specific environmental, cultural and spatial context that they once belonged to.

Hazewinkel focusses on a selection of antiquities that now belong to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Originally excavated from various locations in the Mediterranean, their provenances are at best murky and incomplete, at worst practically non-existent. The mechanisms that brought these works to the Met have deliberately erased much of the information about where they were originally found and whose hands they passed through to end up in the Met’s collection. Hazewinkel has photographed his chosen archaeological objects as they appear today in the galleries of the Met, juxtaposing the sterile museum displays against photographs of landscapes, flora, ocean and sunsets from the Mediterranean nations where the objects were originally made and found, suggestively proposing hypothetical origin spots for them. This contrast highlights what is missing from these works in their current home at the Met.

They can be experienced now only partially, divorced not only from the geographic, climactic and social contexts where they were originally found, but also even from specific knowledge of where that find spot was. Knowledge of where, exactly, these objects sat in the earth for thousands of years is irretrievably lost, and with it any sense of how their materiality related to their surroundings. The dynamic relationship between the sculpted objects and the terrain that they originally occupied is gone. They are capable now only of telling a flattened and homogenised version of ancient art history, aestheticized as art objects rather than historicised as cultural artefacts specific to particular locations. This is not necessarily to say that there is no value in the kind of narratives about ancient art that the Met tells, but it is undeniable that it is only a partial narrative, and in many cases any attempts to supplement it with more meaningful social, historical, and geographical context are severely curtailed by the permanent loss of certain kinds of information about the objects.

There is also a quasi-colonial violence implicit in this loss: who has been deprived by the removal of these objects from their homelands? In Greece, a very visceral sense of loss often comes into play when famous objects in overseas museums have an established provenance from a specific place. It feels like something is missing, a piece of local culture and identity conspicuous not only in its absence but also its presence elsewhere. Most famously, the New Acropolis Museum, pride of place in central Athens and a tourist hot-spot, has pointedly left space in its galleries for the so-called Elgin Marbles, sculptures from the Parthenon that have been on display at the British Museum since the nineteenth century, and whose return to Athens has been agitated for by the Greek government since the modern nation declared independence two centuries ago. Everything is ready to go—pending the return of the sculptures to Greece.

The Elgin Marbles operate at the level of national identity—the most famous sculptures from the most famous monument in the capital city, a potent symbol of the modern Greek nation as a whole in its ever-present connection with its ancient past. Yet the same thing happens on a more local level across the country. The island of Milos, for example, proudly but mournfully celebrates its most famous daughter, the iconic Venus de Milo. In the local archaeological museum there is only a plaster cast of the statue, a cruel facsimile of the original in the Louvre.15 Yet even in her absence the Venus acts as a source of collective identity on Milos, a central and defining fact about the island and what it represents. Smaller scale reproductions are ubiquitous in all kinds of businesses and private homes. The loss of an object from its local context is not just a single moment of deprivation: the absence can linger, reverberating across time. While the connection that the islanders of Milos feel to the Venus de Milo is in some sense constructed and artificial, gaining importance precisely because the object has been afforded fame by its presence at the largest art museum in the world, it is also a visceral and meaningful one.

All ten of the objects represented in Hazewinkel’s series entered the Met’s collections in the early twentieth century with the assistance of John Marshall, then the museum’s sole European agent in antiquities. From their varied and poorly attested find-spots across the eastern Mediterranean, they were all channelled through Marshall’s collecting practice. Small reproductions of photographic negatives of each object, commissioned by Marshall as part of the acquisitions process, invoke the moment when they became institutionalised, so to speak: when they gained the status of being members of one of the world’s most important art museums. The negatives connect the ten works into a coherent series: what unites these objects is that they were brought to the Met by Marshall, and the negatives act as a material reminder of this often-overlooked part of their stories. These early photographs also speak to the aestheticizing interests of the museum in the early 20th century: the complex materiality of the objects is reduced to a one-dimensional photograph, the archaeological object stripped of social context and rendered pure visual art.

How do we make meaning out of the objects we unearth? Who controls this process—and who should? Where has the right to? The Met is one of the most visited museums in the world. The strength of its collection in all kinds of areas is undeniable. But in the case of its antiquities collections, at least, the stories that it is able to tell are often constrained by the lack of reliable information about context and provenance. Amidst his institutional critique of the limitations of the Met and other encyclopaedic museums, Hazewinkel seems to advocate for a kind of knowledge and appreciation of ancient objects that is properly situated, grounded in the unique sensorial characteristics of the places that they were found. How might these objects resonate differently if they had been kept closer to home? What would change if they were held in the small local archaeological museums that are dotted all across the Mediterranean, rather than on the other side of the Atlantic?

Debates about the return of antiquities—not to mention the treasures of indigenous peoples—to their places of origin are often couched in legal and ethical arguments: were they obtained through legitimate and lawful means? is there a moral duty to return objects to cultural or ethnic groups that maintain a historical geographical connection to them? do these legal and ethical factors supersede the value that comes from them being publicly accessible in the museum that owns them? The claims made on archaeological materials in particular can often have nationalistic implications—the Elgin marbles “belong” to the Greek people as an inalienable part of their present-day identity, despite the huge discontinuities between the ancient Athens where they were made and the modern Greek nation state that now lays claim to them. Such approaches can sometimes feed into ethnocentricism, reinforcing divisions and giving support to the notion that culture and history can and should be laid claim to by national communities rather than made broadly available to all.

Yet on the other side of the coin is a genuinely liberational potential that heritage and tradition are able to unlock, especially for subordinated communities, in the face of the homogenising effects of imperialism and globalization.16 It is through the renewal of the past, as Bhabha suggests, that cultural production can truly innovate, interrupting “the performance of the present,”17 and making possible new ways of being in the world that can work against existing power structures. Ultimately, there are no easy answers to questions like these: the troubling imperial legacies of encyclopaedic museums must be balanced against the cosmopolitan and inclusive ideals they embody; the claims of ownership that contemporary peoples and nations make over museum collections must be considered with some awareness of their tendency towards more limited understandings of who culture belongs to. Neither the universalising tendency of the encyclopaedic museum nor the exclusionism of the nationalist or ethnocentric paradigm is without its flaws.18 Who do antiquities belong to? Who ought they belong to? Is “ownership” even the right way to think about it?

In any case, as urgent as these issues may be, the ethics and legalities of museum collection practices are not a central focus of Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X). These problems are there in the background, but ultimately Hazewinkel directs us to pay attention to something that often gets passed over entirely in these debates. As such, his work constitutes a valuable contribution in its own right to urgent and ongoing discussions about museums and their roles in the twenty-first century. Whatever the legalities, whatever the ethics attending to the Met’s antiquities collections, Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (displacements I–X) reminds us that there is—inevitably and unavoidably—a loss associated with these objects’ display in a North American museum. Sunlight, breezes, rain, snowfall, dust, sea spray, birdsong, cicadas: these were a part of the lifeworld of these stone sculptures for so many centuries. But once they were unearthed and shipped off on their roundabout journeys to New York, this aspect of their materiality was lost forever. What is more, any meanings they might have come to hold within the cultural context of their original locale were stripped away. Today on the gallery floor of the Met, these objects can lay claim to the attention of a huge and diverse audience, and they are carefully protected against the ravages of time by glass cabinets, watchful guards and a temperature-controlled climate. But these things have come at a price, and it is one that can never be repaid. They are never—never—going to find their way back to their homelands.

ENDNOTES

1. Originally published in the Wall Street Journal on December 12, 2002, the text has been reproduced in full in e.g. Ivan Karp et al., eds., Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 247–9.

2. Jeanette Greenfield, The Return of Cultural Treasures, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007 [1989]) is a foundational discussion of the issues surrounding repatriation of cultural property.

3. See Donatien Grau, “Introduction: The Encyclopedic Museum: A Catchphrase, a Concept, a History,” in Under Discussion: The Encyclopedic Museum, ed. Donatien Grau (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2021), pp. 4–6 for a concise discussion of the different histories and meanings of these two ways of labelling these institutions.

4. James Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity?: Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 140.

5. See Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity? and Museums Matter: In Praise of the Encyclopedic Museum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). Cf. also Neil McGregor, “The whole world in our hands,” The Guardian (Review Section), Saturday 24th July 2004 <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jul/24/heritage.art>

6. E.g. Mark O’Neill, “Enlightenment museums: universal or merely global?” Museum and Society 2.3 (2004): pp. 190–202, Geoffrey Robertson, Who Owns History: Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure (London: Biteback, 2019).

7. Grau, “Introduction,” p. 7.

8. This was very much the main axis of debate for some years after the Declaration: see e.g. John Henry Merryman, ed., Imperialism, Art and Restitution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), Lyndel V. Prott, ed., Witnesses to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects (Paris: UNESCO, 2009).

9. See now Donatien Grau, ed., Under Discussion: The Encyclopedic Museum (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2021).

10. See the RISD Museum’s online publication Raid the Icebox Now <https://publications.risdmuseum.org/raid-icebox-now>.

11. Alongside artistically-led interventions like those that comprise Raid the Icebox Now, we might add broad efforts at rethinking how and together with what kinds of information museums display their permanent collections in order to foreground some of the troubling dimensions of the recent histories of their objects, which are now occurring at institutions across the world, as well a number of recent geographical grounded survey shows at major institutions that explicitly draw attention to the imperial violence that lies in the background of the objects on display, like Kongo: Power and Majesty (2015) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Ancient Nubia Now (2019) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

12. On which, see especially Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2009).

13. Not to mention they are now very often carried out at the direction of or at least in collaboration with the institution that is the object of the critique: as Andrea Fraser recognised already a decade and a half ago, institutional critique has itself, paradoxically, become institutionalised as museums and galleries regularly encourage contemporary artists to engage critically with their sponsoring institutions (“From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” Artforum 44.1 (September 2005): pp. 100–106).

14. A trend influentially identified by Dieter Roelstraete, “The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art,” e-flux journal 4 (2009), and elaborated in his 2014 exhibition The Way of the Shovel at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the associated publication The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2014). In the years since, the archaeological has become an important and increasingly explicit focus of curatorial activity, especially in places with rich local archaeological heritage. In 2017, the fourteenth iteration of the major art quinquennial documenta 14 was held, for the first time, not only in its traditional home of Kassel, Germany, but also in Athens, Greece, having as its theme Learning from Athens, and focussing to a significant degree on the possibilities that the city’s archaeological past (and its present relationship to that past) offers as a resource for contemporary art: see Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk, eds., The documenta 14 Reader (Munich: Prestel, 2017), and also Brooke Holmes and Karen Marta, eds., Liquid Antiquity (Athens: Deste Foundation, 2017). Over the last decade the non-profit NEON, funded by businessman and collector Dimitris Daskalopoulos, has been producing major contemporary art exhibitions in Greece, as often staged in archaeological sites and museums as in more traditional contemporary art venues. In Italy, the new government-sponsored Pompeii Commitment (2020– ) seeks to activate that archaeological site through an extensive programme of exhibitions, commissions and collecting in contemporary art. Cf. now also on this tendency David Joselit, Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020).

15. A whole series of questions attend the relationship between original and copy, and arise constantly when we are considering ancient Greek statuary in particular, where the history of reproduction extends for two-and-a-half millennia, and much of our understanding of style and output of the famous sculptors of antiquity is today only accessible though copies of their work made already in the ancient world. Fondazione Prada’s 2015 exhibitions Serial Classic in Milan and Portable Classic in Venice, together with the accompanying publication, Salvatore Settis, Anna Anguissola and Davide Gasparotto, eds., Serial/Portable Classic: The Greek Canon and its Mutation (Milan: Progetto Prada Arte, 2015), provide some valuable reflection on issues of originality and reproduction as they relate to ancient Greek statuary from a curatorial and art historical perspective.

16. Cf. Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), and within the specific context of contemporary art, Joselit, Heritage and Debt.

17. Bhabha, Location of Culture, p. 10.

18. Joselit’s very recent analysis of the landscape of global contemporary art in Heritage and Debt brings into relief the recurrent tension between cosmopolitan and nationalist impulses in contemporary artistic production that is grounded in heritage.