Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (Displacements I-X) 2010-2020

A series of 10 digital chromogenic prints on aluminium with Diasec face-mounting

116 X 158 CM

Ed 3 + 1 AP

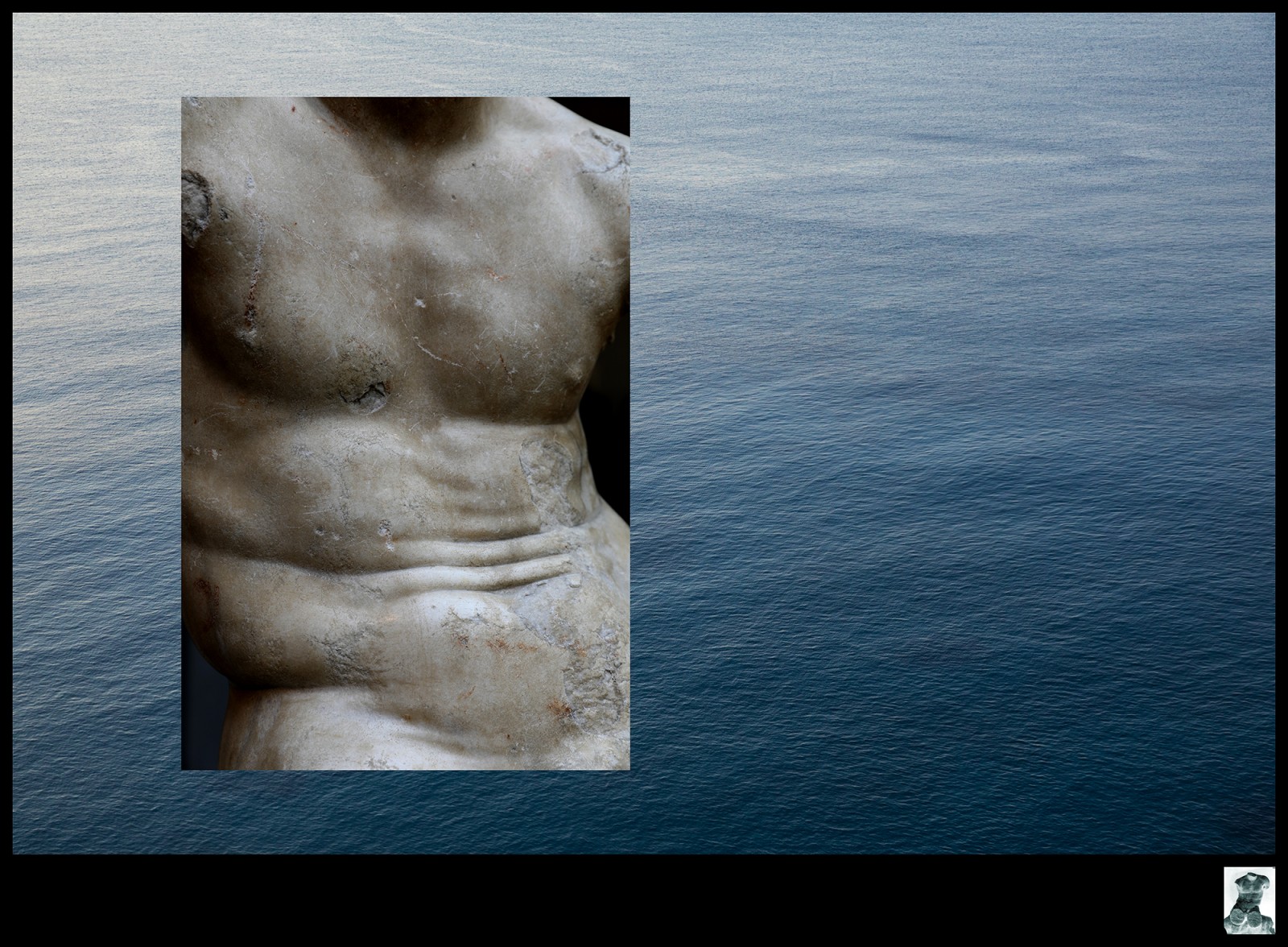

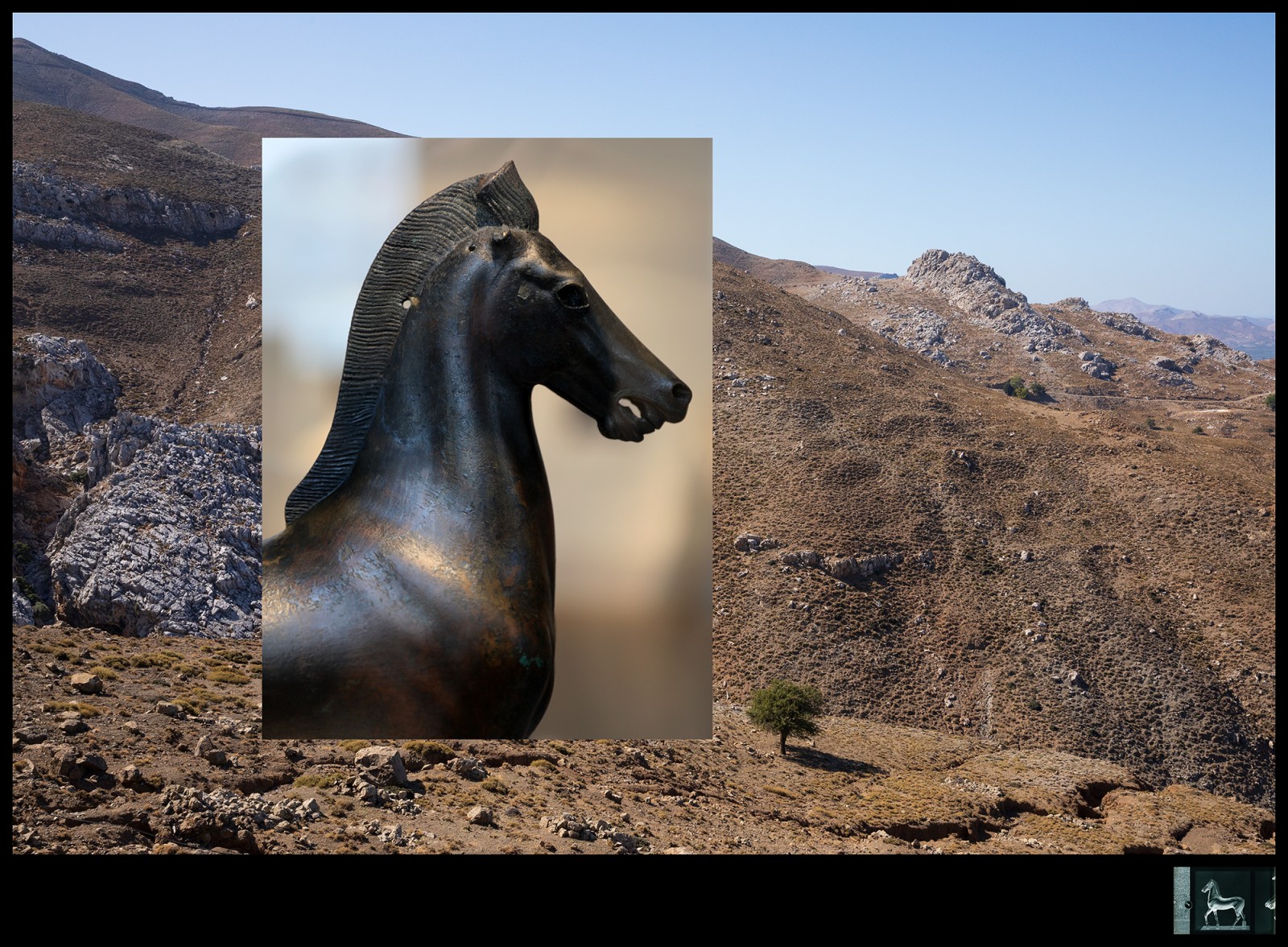

1: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement I) JM 758 / Met 11.55

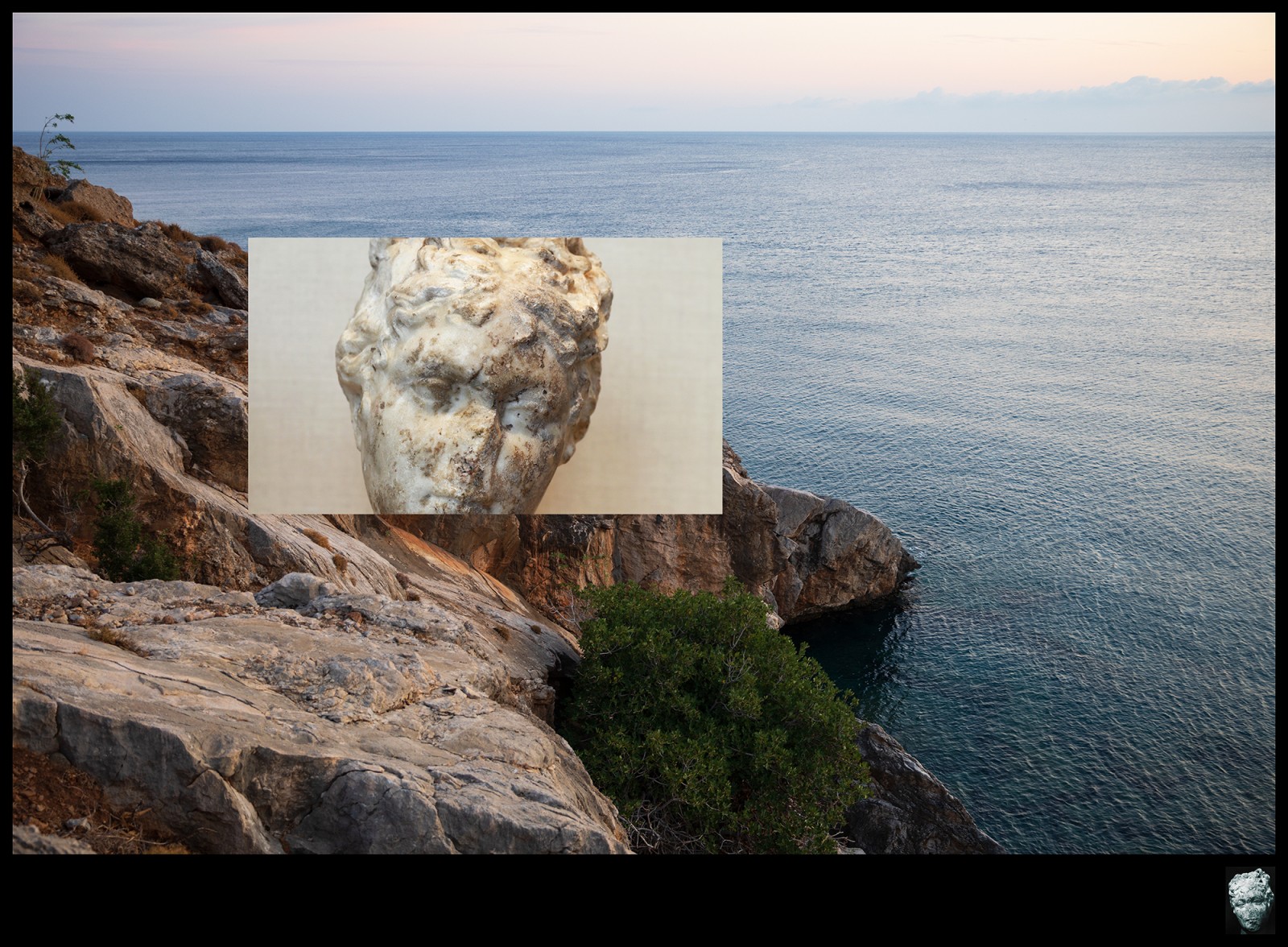

2: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement II) JM 237 / Met 07.306

3: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement III) JM A.1.5.7 / Met 20.200

4: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement IV) JM 238 / Met 11.100.2

5: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement V) JM 548 / Met 27.45

6: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement VI) JM 777 / Met 26.60.2

7: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement VII) JM 702 / Met 23.69

8: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement VIII) JM 237 / Met 11.185a-d,f,g,x

9: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement IX) JM 237 / Met 06.311

10: Journeys In The Lifeworld Of Stones (Displacement X) JM 1724 / Met 26.60.37

To receive a digital catalogue of the project, including images of the ten artworks, artist notes accompanying each of the artworks, and the essay Presence Elsewhere by Paul. G. Johnston - Department of Classics Stanford University- commissioned by Sumer, Aotearoa New Zealand, on the occasion of the exhibition Journeys in the Lifeworld of Stones (Displacements I-X) 2022 click below.

DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

Each of the ten photographic compositions focuses on a displaced cultural artefact now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Met) and trace that object’s journey from its place and culture of origin to the galleries of the Met.

At the lower right margin of these large chromogenic prints is where each pictorial journey mapping begins. There we find a digitised reproduction of an archivally sourced late 19th century photographic negative that represents each artwork’s ancient subject.

The presence of these small images is pivotal to understanding this suite of works. As is the knowledge that these images, and others like them, were generated during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to meet the needs of the commercial apparatus associated with the (now dubious) trade and acquisition of cultural artefacts by some of today’s largest and most well-known universal museums. These small images are thus associated with contemporarily maligned policies, practices and politics associated with what is sometimes called the great collecting age, during which new world institutions scrambled for old world cultural legitimacy.

It is relevant to note that the archivally sourced images are drawn from the John Marshall Photographic Archive, which is held at the British School at Rome, a contemporary interdisciplinary research centre that hosts artists undertaking experimental research, but whose core business focuses on more traditional historical and archaeological subjects. John Marshall (1862 – 1928) was a British scholar of classical art, with expertise in Greek and Roman sculpture. Between 1906 and 1928 he was also the European agent for the acquisition of antiquities to the Metropolitan Museum of Art; by today’s standards these two professional responsibilities can be described as ethically conflicting roles.

The small archival image in the lower right margin of each work is inextricably linked to the contemporary museum interior image that occupies a more central position in each composition. That image represents the same commercially captured cultural artefact that features at lower right margin as it stands today in the grand, enormously profitable, tourist teeming, galleries of the Met. All the contemporary tensions that are strung tight between those two inextricably linked images are then more broadly contextualised by landscapes, seascapes, and atmospheric conditions, bringing to mind the palpable, sensible, aesthetic qualities,1 the material, environmental, spatial, and cultural contexts of the ancient and more recent Mediterranean territories and cultures from which they emerged and belonged to.

1. My use of the term aesthetic here does not refer to conceptions of beauty or taste, rather it invokes its Classical Greek etymological origins ‘aisthetikos’: perceptible by the senses.’

It is easy to think of stone as cold, but marble is a stone that quickly takes the warmth of the sun and if we consider that many ancient statues stood about in the landscape, their bodies become softer, somehow more alive in our minds.

Time is of the essence in this photograph, which is the first of ten that I have been developing for about a decade. Here however, the meaning of that stale cliché is flipped, rather than urging the need to make haste, in this context the opposite is true. The time taken to make this work has somehow seeped into it, becoming a part of it. There is a lot of waiting in this work, which evokes among other sensations, the exquisite deep stillness that comes with being forgotten and the exuberance that comes with resurfacing.

Geological time, archaeological time, deep time, oceanic time, good times, bad times, and (to bring it back to the camera), exposure times mingle with the limbo of the photographic archive and the temporal mash-ups of encyclopaedic museum displays, generating the pulse of this work.

In the lower right margin is a small image of a digitised gelatin dry-plate negative (c.1910) sourced from a photographic archive in Rome. It represents the badly damaged torso of a young Herakles that was made in 360 BCE. A disquieting sense of serene brutality emerges at the breaks where the legs, arms and head once joined this torso. The breaks appear to be intentional but we can’t be certain, early Christian brutalisation of ancient statues, and the related desecration of pre Christian temples and sanctuaries is not always easy to identify. The archival image represents one of nine large glass plates (each measuring 39.5 x 29.7 cm) that depict the broken figure from different perspectives. They were made to encourage the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York City to acquire the torso in the period during which new-world institutions scrambled for old-world cultural legitimacy, which was itself an exertion of power with roots in imperialist strategies. The archival image is paired with a larger image, of the same torso, that I captured in available light in the galleries at the Met in 2017.

These images spill out into the light reflecting off an open, wind ruffled sea not far from Athens, which is where this young Herakles was created some 2300 years earlier.

This sets me thinking about the special bond between materiality of things and place and of homecomings, of all kinds, as it reminds me of the exquisite sensation of cool air rushing into my lungs after swimming underwater for as long and far as possible.

Colours, like stones, journey though the Lifeworld, typically setting out as minerals or pigments. In archaic times Black Sea Cinnabar rendered bright reds, Orpiment from Ephesos offered golden yellows, Lazurite from Afghanistan provided deep blues, while Chrysocolla from Attica furnished a forest of greens. Colour in the ancient world, more than today, sent the beholder on imagined journeys. In ways not dissimilar to the songlines of ancient Australia, colour-paths may have functioned as a kind of chromatic compass aiding journeyers on their own paths through the lifeworld.

Commonly held perceptions fuel the idea that the marble bodies of antiquity gleamed whitely and brightly in the shadowy ancient world. That conception looms large in our contemporary collective imagination, but it is a misconception, a material misunderstanding of antiquity with threatening contemporary social legacies.

Previously unnoticed or simply ignored pigment traces identified on the broken bodies of antiquity have recently become a focus of archaeological scholarship. These colour residues provide data that proves that much archaic and classical sculpture (and architecture) was brightly painted. To some contemporary imaginations, visions of a brightly coloured ancient world may seem lurid, loud, even distasteful or garish.

As well as challenging our visual imaginings of antiquity, these delicate chromatic residues help debunk violent ideologies put forth by white supremacists in their misguided legitimising claims of being connected, genealogically, to the whiteness of classical antiquity.

Colour trace research is doing more than recasting how we imagine the remote past, it is also contributing to the swelling corpus of research which, in various ways, supports the important work of decolonising museum collections, especially those collections that are founded on imperial thinking and activity.

This body of photographic work does not confront those issues head on rather it approaches them obliquely. It aims to draw to attention to an intimate sensorial, personal dimension to, and the ongoing collective cultural consequences of a museologically stimulated amnesia toward cultural plunder. In this way it signals what might be considered a persistent wounding.

In the lower margin of this photograph is a digitised image of a dry-plate photographic negative (c.1905) sourced from the John Marshall Photographic Collection, which is held at the British School at Rome (BSR). This idiosyncratic collection is comprised of images created principally as aids in the late 19th and early 20th century commercial apparatus associated with the often-dubious sale of cultural artefacts to universal museums.

Here the subject is a once brightly painted late 6th century BCE marble representation of a young woman, a kore, said to have been found on the island of Paros. Elegantly attired in a style originating in the Greek coastal cities of Asia Minor, this young woman pulls her linen tunic tightly across her legs as her cropped cloak cascades in layered folds to her waist. I photographed her as if under a spell I was following her through the galleries at the Met, where to me she appeared to be cutting a path to the nearest exit.

The cave like formations of the rocky landscape recall the need for shelter and earthy activities, perhaps the search for minerals, to be ground into pigments to personalise objects of everyday use. This young woman powerfully holds her ground; she seems to know where she is headed, perhaps more clearly than we do.

Seafarers will tell you that the horizon is roughly 22 km distant (about 12 nautical miles). This is true if you are standing on the deck of a ship, but if you are sitting in a life raft, or on a surfboard, the horizon is about 4.5 km away. Horizons are set by the distance that separates our eyes from sea level. This handy formula helps to work it out – square root (height above surface / 0.5736) = distance to horizon.

A close friend once said to me ‘it’s always better to be just below the horizon, that way people can sense your emergence but can’t focus on you as a target’.

The altitude of the landscape in this photograph is roughly 700m above sea level, so its horizon is roughly 122 km away, which here is half way to the Libyan coast. Considering the fixed gaze of this remarkable marble portrait (c.130 CE), and what we know about whom it represents, sets us thinking about what, in this context, she may be sensing.

Meet Marciana, the elder sister of the Roman Emperor Trajan. Trajan’s reign (98-117 CE) is best known for territorial expansion, public building works and the development of social welfare policies, most notably the alimenta which saw the use of public funds, generated by estate taxes, to support orphans and poor children. Marciana and Trajan were close. Marciana had one child, a daughter named Salonina Matidia. Trajan, although married, remained childless. Following the death of her husband, Marciana and her daughter lived with Trajan and his wife. Marciana and Trajan often travelled together on campaigns; she had his ear and assisted him in important decision making. Marciana was a powerful person, perhaps more in the human sense than the political, or perhaps equally in both.

When I think about Trajan’s achievements, and how the male dominated recording of history brings them down to us, I can’t help but wonder whether his social welfare ideas were actually her ideas, or perhaps their shared ideas, which surfaced in sea gazing conversations about love and care and roles within families and the importance of multifarious family forms.

Unlike the position of this life-sized portrait in the light filled yet airless galleries of the Met, here Marciana gazes across the Libyan Sea toward the horizon. This photograph’s archival source is a gelatin silver print drawn from the John Marshall Photographic Collection in Rome, which I have drawn upon for this entire body of work. In it Marciana wears an elaborate hairstyle, however with my portrait of Marciana I am more interested in the precise engraving of her eyes, which to my mind are a way in to knowing her. As with all good portraits, this portrait of Marciana leaves you with a sense of embodied mutuality, the sense that you somehow know, or better, share something with the subject. And it is precisely this fragile hard to pin down sense of connection with others that keeps us all connected, especially in times of difficulty. With this Journey in the Lifeworld of Stones those of us that have ever gazed out to sea, at uncertain personal horizons, may sense the ongoing spirit and support of a woman long gone.

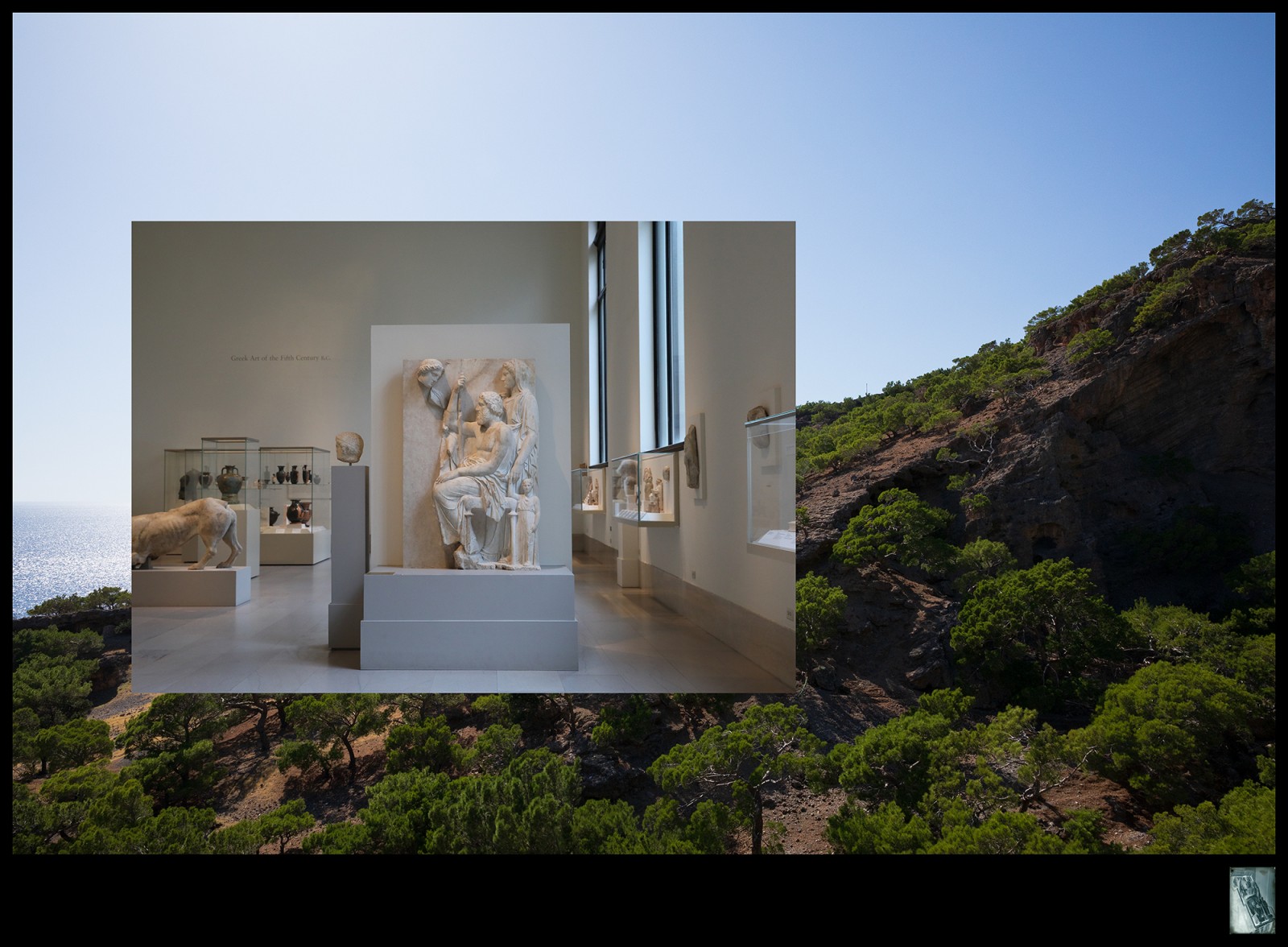

During the ten years that this body of work has been in development the working title of this photograph was A Family Group. That fit neatly with my evolving understanding of the role of family in contemporary and ancient Greek societies, and on a more visceral level, when thinking about my own family, my at times times prickly place within it, and how together we have navigated profound loss. The grave-marker at the centre of this work reminds me of the inescapable archaic timelessness of grieving.

The inscriptions that once accompanied this grave-marker are missing, much of this family’s story remains unknown. To be honest we can’t be certain who is mourning whom here. Are the seated and veiled figures parents mourning their daughter? Or is she mourning her father, or her mother, or both? An intense solemnity and profound sadness reaches us through this uncertainty, what touches us is the ache of loss.

In the lower right margin of this photograph is a digitised reproduction of a gelatin dry-plate negative (c.1911) rescued from the temporal limbo an archive of images that were generated to support the sale of ancient objects to new-world museums; an activity that displaced the objects from the sensorial meanings of their original spatial, material and cultural contexts. In it we see the gravestone of a family group that has been removed from a cemetery and is ready to be trafficked. Acquired by the Met in 1911 from G.Yanacopoulos (a dealer of antiquities based in Paris), this late classical stele (c. 360 BCE) was originally set up by a family from Attica, under the Attic sky. It is made of Pentellic marble, which is cut from the earth of Attica. Mt Penteli, on the NE outskirts of contemporary Athens still functions as a marble quarry.

For me there is a special materially triggered togetherness at play here, a form of material semiosis, wherein our capacity for an embodied sensorial knowing emerges from the mingled awareness that this family and the stone that marked the end of their lives are of the same place, or better, that they are the same place, they are autochthonic. This is where the word displacement, common to the titles of all the photographs in this series, really starts to hum, prompting a cascade of questions concerning the contemporary function and relevance of encyclopaedic (or universal) museums. What meaning can be made in an experience of this grave-marker in the tourist filled galleries of the Met? What social tensions emerge from such hermetic heterocosms? What knowing might be lost in displacement?

Walking backward through the word paradox (with a sight line borrowed from the Māori whakataukī - or proverb - Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua, which can be translated as I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past), we arrive at the Greek para meaning ‘contrary to’ and doxa meaning ‘opinion’; doxa has further links that extend back to dokein which means ‘to appear, to seem, to think’.

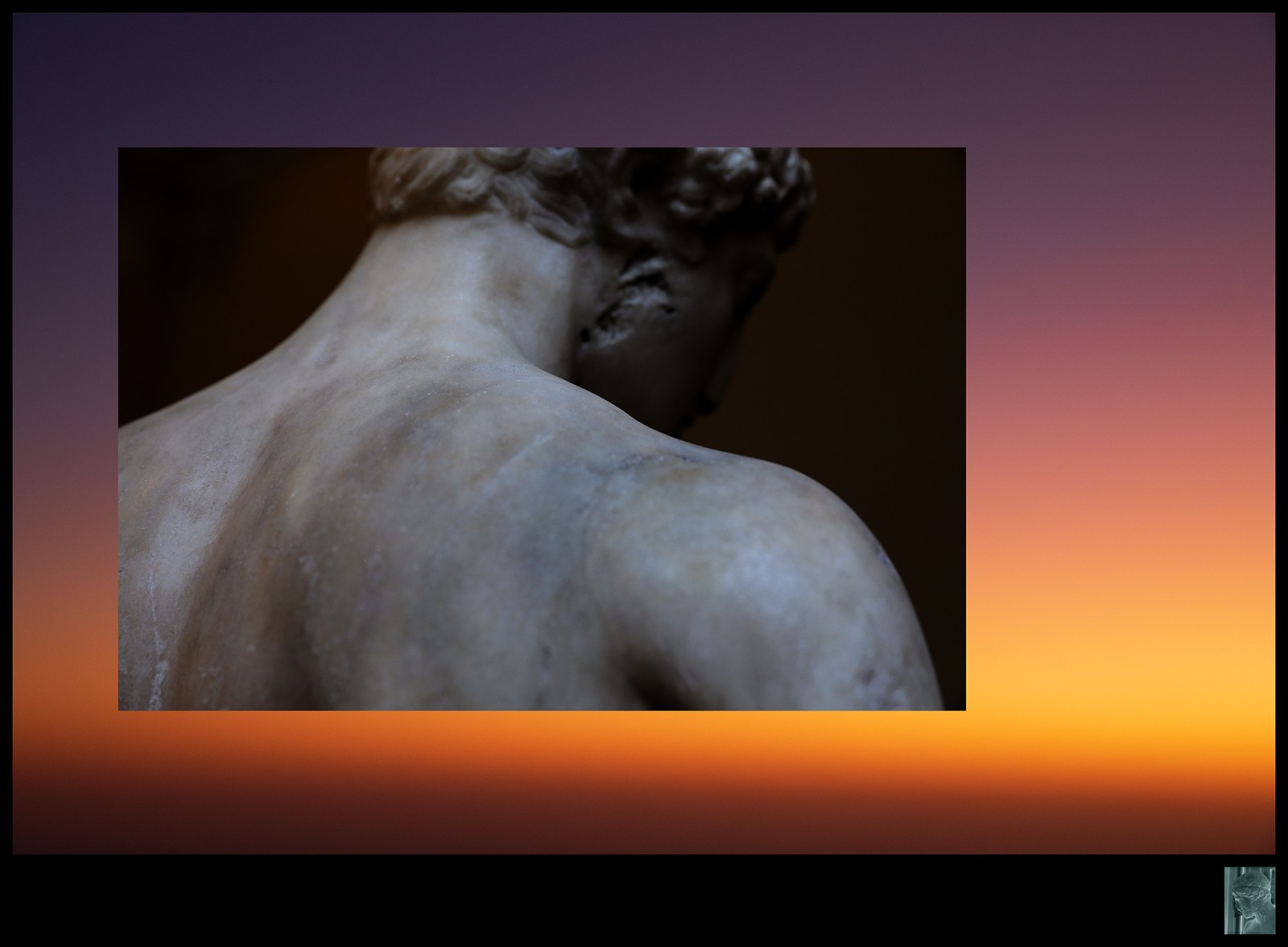

The central image of this photograph teems with paradox contextualised within an atmosphere of uncertainty. The setting could be the beginning or end of any day - dawn or dusk, sunrise or sunset. Without knowing where I captured this image you can’t be sure. The uncertainty is intentional it aspires to fruitfulness.

Borrowing another perspective (this time from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle), we learn that the closer we examine the momentum of nature’s smallest particles (quantum particles) the less we can know of their location and vice versa. This sheds light on a particular fuzziness essential to the very nature of nature.

Here stone is tender. The intimacy between a young girl and her birds is not just academically symbolic, it is soul stirring and elevating. Anthropocentrism is alien to children. Here creatures of land and sky merge (formally and conceptually), feeding one another love, trust and tenderness. In this intimate moment, fixed in stone, nothing else exists in their fuzzy shared world except their exquisite exchange which is witnessed by a memory in the shape of a fragmented bird.

This is the grave stele of girl who died young, perhaps only 8 or 9 years old. It was made circa 450-440 BCE of Parian marble, a local stone, known for its fine-grained whiteness and its light capturing qualities. Standing at 80 cm we might imagine this stele as a mirror reflecting Dovegirl (as I have always called her) at her death. It was discovered on the Greek island of Paros in 1785 and was promptly shipped to the Isle of Wight (UK) where it became a possession of Sir Richard Worsley of Appuldurcombe House. In the early 1800’s its ownership was transferred to the Earls of Yarborough at Brockelsby Park Lincolnshire (UK) where for the next 100 years or so successive Earls of Yarborough called her theirs. In 1927 under advice of the antiquities agent John Marshall, the Met acquired her. The acquisition process was supported by photographic prints made from the gelatin dry-plate negative represented in this photograph’s lower right margin.

All of this ownership and transference has at it essence the act of taking - taking away, taking advantage, taking possession, the list goes on...running counter to the exquisite exchange represented.

There is another image reproduced here, it represents a plaster copy of Dovegirl’s stele as it stands today in the sunlit courtyard of the small overlooked Archaeological Museum of Paros. If you find yourself on Paros, pay her a visit, take a moment to look into the sky and enjoy the abundant birdsong.

The climate-controlled world of photographic archives prioritises the information carrier, which, in that specific context, means the material that supports the image in either negative or positive states. While a photographic archive’s technical facility prioritises the materiality of photographic artefacts the most engaging conversations that I have with archivists, revolve around the image itself and how the image might be reimagined.

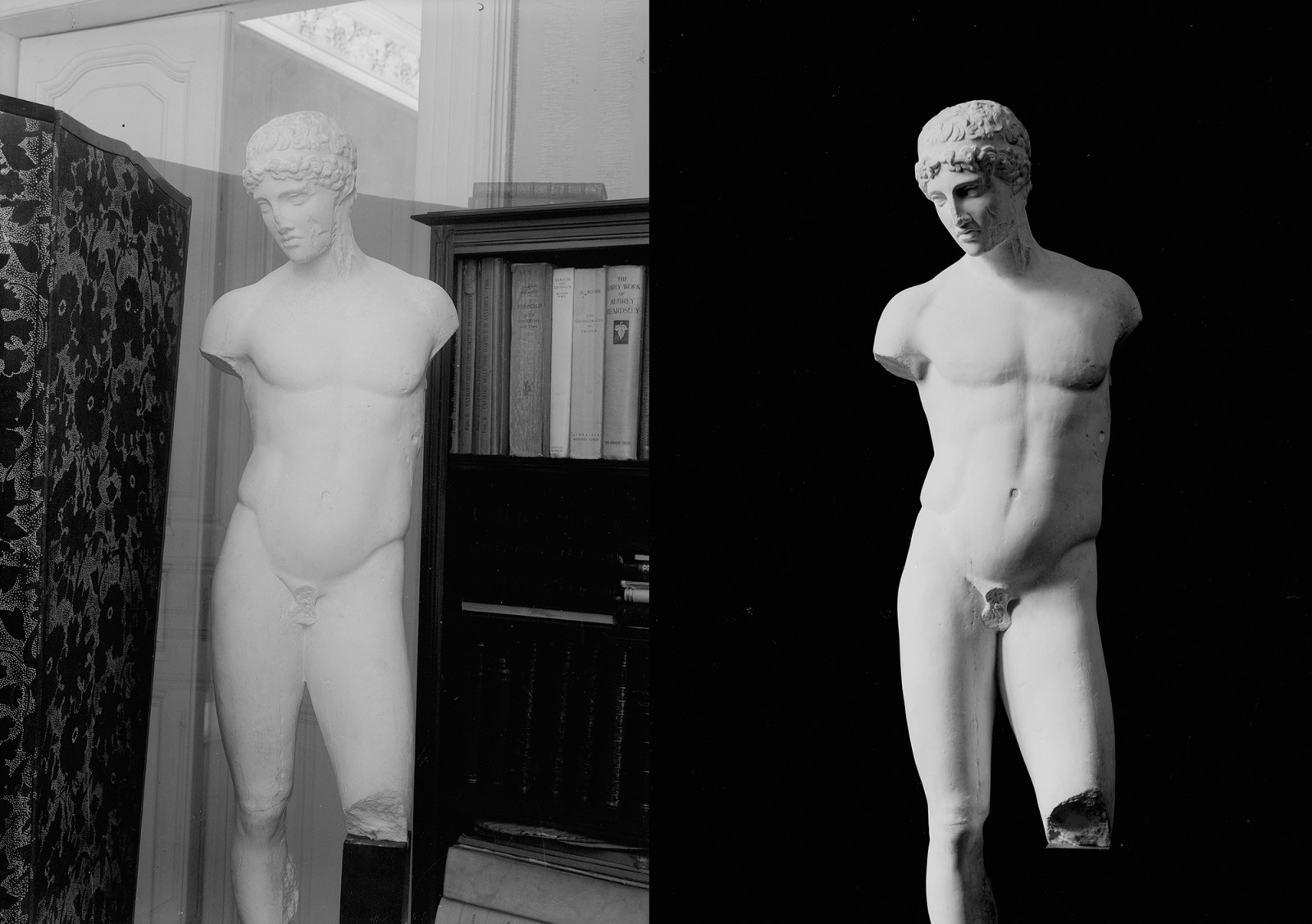

The archival material at the inception of this body of work is drawn from the little known John Marshall Photographic Collection, which is held at the BSR. The collection is modest in scale comprising approximately 2500 gelatin silver prints and roughly 800 gelatin dry-plate negatives. The principle subject of these commissioned and collected photographs is Greek and Roman sculpture.

John Marshall (1862-1928) was a highly esteemed scholar of Greco-Roman sculpture and a dealer of antiquities. During the period in which he worked that problematic dual role is likely to have appeared less two-faced than it does today. From 1906-1928 he was the exclusive European agent for antiquities to the recently established Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The glass negative reproduced in the lower margin of this photograph is one of eleven involved in the Met’s 1926 acquisition of the subject of this photograph’s central image. A 1st century CE Roman marble copy of 5th century BCE Greek bronze original. Seven of the eleven archival images representing the naked male figure appear to be photographed in Marshall’s domestic setting providing us a rare tantalising glimpse into his personal life. The other four, bearing homoerotic and stylistic connections with much later works by Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989) and Bruce Weber (b.1946), were created in 1926 by the Roman photographer Cesare Faraglia under controlled studio lighting conditions.

For me, the temporal distance between the making of Greek bronze and its Roman marble copy is occupied by questions that revolve around the motivations for making art objects and the social, political and cultural implications of the places they are made for. The original bronze was created to commemorate a young man’s victory at games; it mostly likely stood outdoors amongst trees in a sanctuary. The Roman version was made to satisfy the emergent Imperial thirst for sensual objects to decorate their bathhouses and the villas of the wealthy. So why did I make this photograph? I made it for Marshall who, through my sustained engagement with the images that he collected and commissioned, I feel like I have got to know. We are both gay men and I suspect we would have got along. However his life was lived at a time when our sexuality required codification, his archive can be read as an entanglement of that, and although I don’t agree with his museological politics, I understand and celebrate his desires.

When they saw that Patroklos had been slain,

that one so strong, so young and so valiant,

Achilles’ horses began to weep;

their immortal spirits enraged

to witness the handiwork of death.

They reared their heads and shook their manes,

scarred the earth with their hooves, and mourned

Patroklos, rendered lifeless, gone,

now useless flesh, his soul no more,

defenseless, never more to breathe,

cast out of life into nothingness.

Zeus saw the immortal horses weep,

and was moved. “I acted thoughtlessly

at Peleus’ wedding”, he said,

“better we had never given you as a gift,

unhappy horses! What business did you have there

amid the wretched human race, fate’s diversion?

You who will never die, will never age,

only fleeting woes may plague you. Men, though,

have drawn you into their own miseries”.

And yet it was for death’s eternal woes

that those immortal horses shed their tears.

The Horses of Achilles

Constantine P. Cavafy

C.P. Cavafy: The Canon. The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems, trans. Stratis Haviaras, Athens: Hermes Publishing, 2004. 33. Reproduced courtesy of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, University of Harvard.

Again we stand together before death, or more accurately, before a marker of a life lived, that brightly burned and early ended. Some scholars say that this is the most intact grave-marker of its type to have survived the 2550 years since it was created, in the period we now call Archaic. There are many remarkable things about this object, for example it is a little more than 4m in height, but what captures my imagination is that the inscription on its base is composed from the personified perspective of the stone itself. Here stone has voice and it speaks with the intimacy of someone close to the family that this young man, Megakles, was a part of.

“to dear Me(gakles), on his death, his father and dear mother set me up as a monument.”

Having voice and being heard is an important aspect of being a part of and contributing to something (like a family), but in the parlance of separation, or diaspora (from the Greek diaspeirein: dia - across, speirein- scatter) that dislocated being a part of something is sometimes most eloquently expressed through present absence, and silence. I am more apart from my family than not, and recently I’ve come to appreciate that that is my part in my family (which has diasporic origins). Much of contemporary society is diasporic, increasingly the movement of people comes in floods, even as nation-state borders become increasingly brutal, and inhumane. And so, we collectively become increasingly dependant upon threaded stories of connection, scattered rhythms, poetry and tastes, dances and rituals, of the perfumes of plants and family members we may never have known, and their experiences that have been transferred to us (often in the form of objects) that inhabit and shape our memories.

Megakles’ stele is indeed a remarkable object and its journey in the lifeworld is one of scattering, of being purchased, traded, bartered, freighted. As it stands today at the Met it is an assembly of fragments acquired by various means over 40 years (1911-1951), which is more than twice the number of years that Megakles lived under the Attic sky. Today his material afterlife exists in bits and pieces in various museums and galleries in different cities around the world. His right forearm is in a museum in Athens (I recently went looking for it, to no avail), the head of his younger companion (presumably his little sister), is somewhere in Berlin while the 5 fragments reassembled in this photograph stand beside the flooding traffic of 5th Avenue.

The draped figure in this photograph is Eirene the personification of peace. While her right leg is slightly advanced she appears powerfully set, she holds her ground. Unusually, we know precisely the year that this Eirene was made, 375 BCE. We know this because of its sudden appearance on some relatively recently excavated painted vessels and because Pausanias, the 2nd century Greek writer, describes seeing it in the ancient Agora at Athens.

My point of departure is different. I’m setting out from this personification of peace into the age-old battle for authority between images and words, which in the age of fake news and Photoshop assumes different perspectives and relevance.

The following story is rooted in conceptions of union between two Olympian heavy hitters, Hera and Zeus. Then it descends into a more bloody battle between Hermes and Argus, which, allegorically speaking may be considered as the conflict between words/language/communication (the purview of Hermes) and sight/vision (the purview of Argus).

The players:

Hera: wife of Zeus, mother of his legitimate children, known for jealously and rage.

Zeus: husband of Hera, lover of many others, represents authority based on power, is considered a projection of law and justice.

Io: one of Zeus’ many lovers (Antiope, Callisto, Danae, Leda, Semele and Maia are others). Io represents disguise and submissive acceptance.

Hermes: accepted illegitimate son of Zeus, represents language, words and communication.

Argus: the 100-eyed giant represents sight, surveillance and uninterrupted vision.

The plot:

Hera learns of Zeus’ love for Io and flies into a jealous rage. To protect Io from Hera’s wrath, Zeus transforms Io into a radiant white heifer. Suspicious of her husband’s transformational proclivities, Hera sends in Argus to keep a close eye (or 100), on Io. In response Zeus deploys his son Hermes, as assassin, to kill Argus. Io flees the messy scene and little attention is further payed to her. But that is not the end of it. Hera makes one more (kind of creepy) gesture. She removes from dead Argus his multi eyed skin and drapes it upon the body of her favourite bird, the flightless peacock, which comes down to us as symbolic of the decorative rather than the meaningful.

The power of images and power of words are not the only themes central to this story, sound is also present, and it too reverberates with vestiges of the combative. Soaring in violent triumph Hermes (metaphorically) flies through our skies lyrically playing his lyre while the ground bound decorative bird squawks its inharmonious song. In this way the defeat of images by words is ongoing, it is perpetual, or as Michel Serres puts it “sight gazes without seeing at a world from which information has already fled.”

Make peace, personify it, we need it.

Serres, The Five Senses. A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. Translated by Peter Cowley and Mararet Sankey. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2008. p 51

The material subject of this work is a human-scaled marble head of a young girl, which has, at some time since it was made (between 100 BCE and 100 CE), been removed from its body. The archival impetus for this work is a small (10.5 x 8cm) gelatin silver print that I discovered in a solander box titled ‘Suspicious - Forgeries’ in the John Marshall Photographic Collection at the BSR. The head was acquired by the Met in 1926, last time I checked there was no provenance associated with it listed on their website. In this photograph there is a sense that the young girl is peering through the back of the landscape image into a world that is familiar to her. It is as if she is checking to see if it is safe to re enter the beloved space that she remains inextricably a part of. Pulsing through all the works in this series are cadences of encyclopaedic museum dread that call for greater institutional accountability in relation to the slow, ongoing, cultural violence that some museum collections continue to exert. Issues associated with this are debated in many languages - political, legal, scholarly and poetic (to name a few), these photographic Journeys In The Lifeworld of Stones (Displacements) aim to highlight, participate and contribute to that discourse through a different language. It is seems appropriate then to arrive at displacement number X of X in a territory bounded by two languages between which you can further understand what I have tried to do in my own language.

From ‘A long Duration of Losses’ by Felwine Sarr and Bénédict Savoy, ‘the extraction and deprivation of cultural heritage and cultural property not only concerns the generation who participates in the plundering as well as those who must suffer through this extraction. It becomes inscribed throughout the long duration of societies, conditioning the flourishing of certain societies while simultaneously continuing to weaken others’.

And again from Cavafy

Although we destroyed their statues

and ran the gods out of the temples,

that doesn’t at all mean that they’ve died.

O land of Ionia, they still love you,

they still hold you dear in their souls.

When the August dawn washes over you

the vigor of their lives enters the air itself.

And on occasion an ethereal young figure,

difficult to discern clearly, passes over

your hillcrests, a swiftness in its stride.

Ionic

Constantine P. Cavafy

A Long Duration of Losses is drawn from the 2018 report by Senegalese economist, musician, and academic Felwine .Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy titled The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Towards a New Relational Ethics commissioned by the President of the French Republic Emanuel Macron for the Ministère de la Culture Republique Française. The quotation can be found on page 8

C.P. Cavafy: The Canon. The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems, trans. Stratis Haviaras, Athens: Hermes Publishing, 2004. 62. Reproduced courtesy of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, University of Harvard.