Fugitive Mirror : Working with the Marshall Collection

British School at Rome 2010

Fugitive Mirror: Working With The Marshall Collection was the first public presentation of my ongoing engagement with the John Marshall Photographic Archive held at the British School at Rome.

John Marshall (1862-1928) was a British scholar of antique sculpture and commercial agent of antiquities. The archive of images that he collected and commissioned reflects both his working practices and the melding of these roles. From 1906 until his death in 1928 Marshall was the exclusive European Agent of antiquities to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. His archive comprises approximately 800 early 20th century gelatin dry plate negatives and approximately 2500 gelatin silver prints documenting (principally) Greek and Roman sculpture.

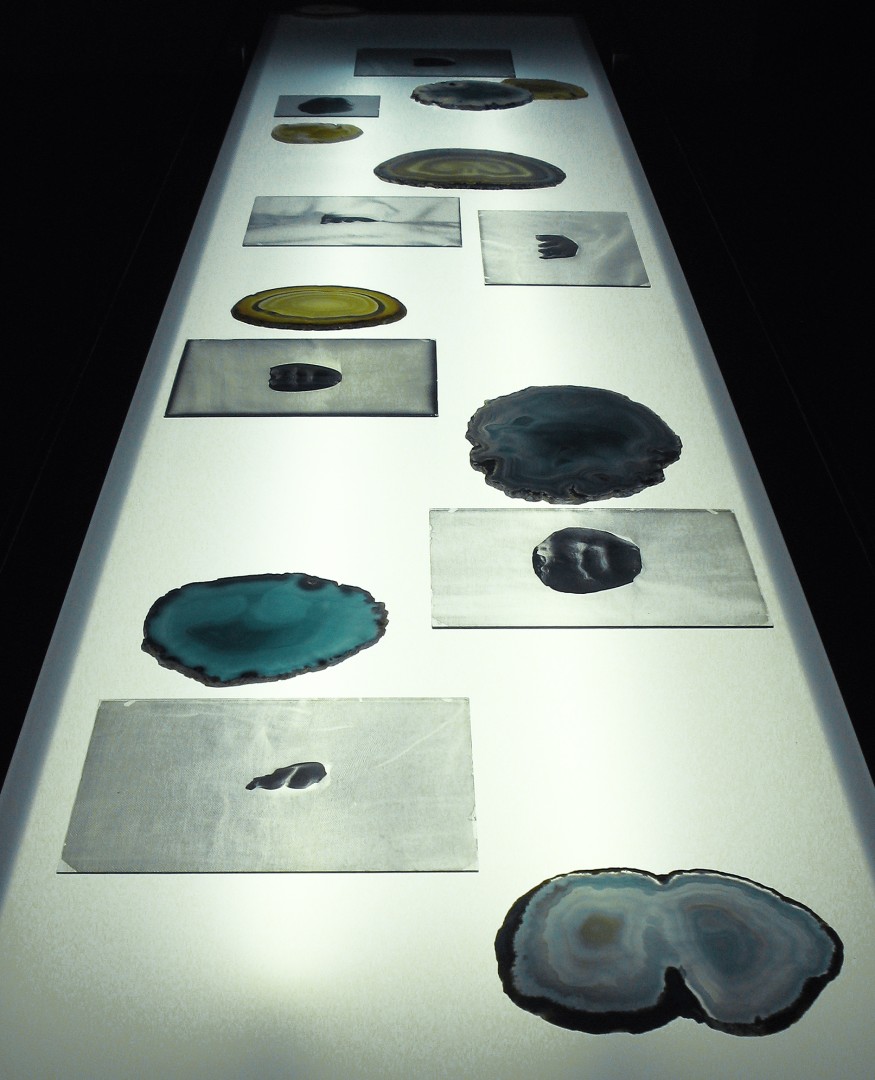

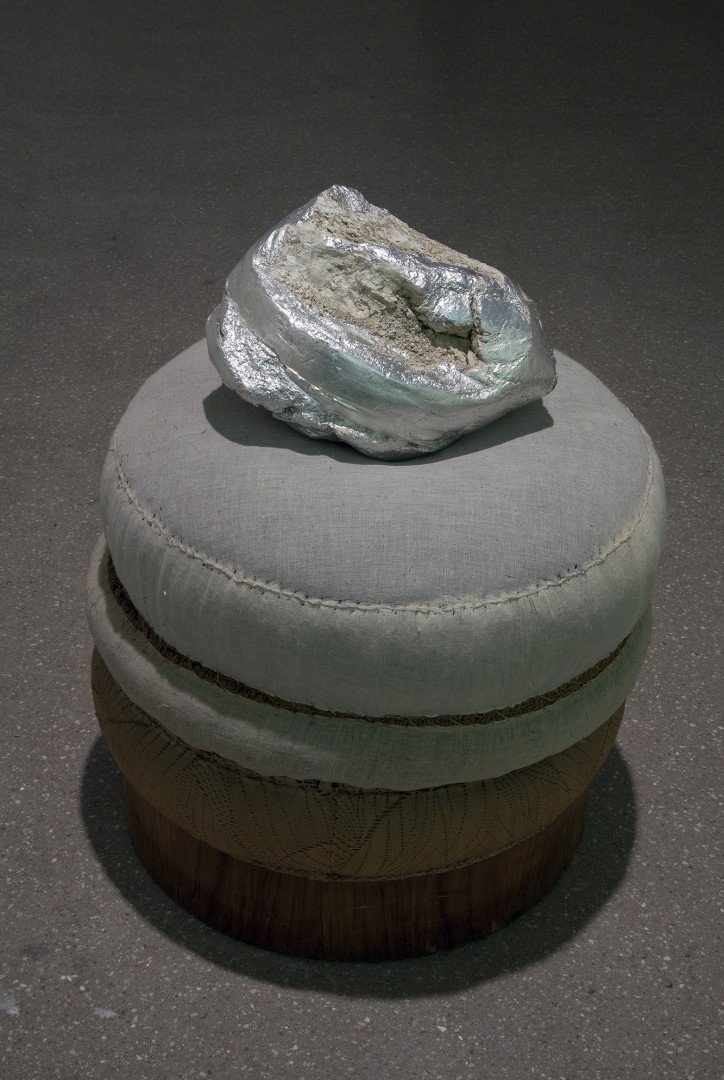

Working with the gelatin dry plate glass negatives of the Marshall Collection, I developed a body of work in response to the fragile materiality of these photographic artefacts and of their subjects. The exhibition included photo-mediated screen-prints on both sandpaper and silvered linen, audio works, sculptural components - including reworked found objects - and a customised light table on which I presented a selection of the glass negatives alongside thin slices of agate which were described by Roger Caillois as "image bearing stones".

WE LIVE TOGETHER IN A PHOTOGRAPH OF TIME

artist notes accompanying the exhibition -

the title is borrowed from the song Fistful of Love by Anohni and the Johnsons

If Anohni is right, then this line from their song Fistful of Love begs the question, where do we die together? Roland Barthes suggests that the catastrophe of our own death, the inescapable knowledge of our own death, is located in every photograph.

I am not so sure, perhaps if we focus our concentration on images of the human form, or better, images of images of the human form, he is right. That is what I have been doing for the past four years, beginning in 2006 with my introduction to the climate-controlled world of the British School at Rome Photo Archive, where I first met John Marshall who lived between 1862 and 1928.

The important, yet little known Marshall Collection consists of more than 2700 late 19th C and early 20th C silver gelatin photographic prints and approximately 800 silver gelatin dry plate glass negatives that document principally Greek and Roman sculpture.

I like glass. It is a thoroughly contemporary material, a curious substance, an amorphous solid. It curtain- walls the cities we inhabit, it reflects ourselves back to us as we shave in the morning or apply our make-up or both. It helps us to decide if we are ready or not, each morning, to face our day. It also has an ancient past and can be traced back to 3500 BC to Mesopotamian origins. It has a close relationship with the timeless science of optics, and by association with image making.

If the history of the photographic portrait is considered as a series of attempts to immortalise the dead what happens when a photographer lights the non-living with a sensitivity usually reserved for the living, and then captures a portrait, of a portrait? Are we simply then twice removed from the essence of the original subject, are we suddenly placed a the vortex created by a dog chasing its own tail? Or are we suspended in the haunted space between the living and the dead?

From 1905 to 1928 John Marshall was the sole European agent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. During this period he played a central role in the assembly of their Greek and Roman Collections. Before this, between 1894 and 1904, he and his partner Edward Perry Warren, were responsible for assembling the collection of Greek and Roman Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which was considered the premier collection in America at the time.

Working from Rome, Marshall commissioned Italian photographers (frequently Cesare Faraglia), to capture images of antiquities as they came onto the market. With these images he prepared comprehensive dossiers for consideration by the acquisition boards of the MET, the BMFA and other important collecting institutions. Many of the captured images are themselves exquisitely beautiful and can be considered works in their own right. These early photographic images document an enormous variety of objects; terracottas, marbles, bronzes, as well as works crafted of ivory, bone, and silver. Many are now considered masterpieces of antiquity; some are considered master works of forgery.

I like stealing things. As I was in the later stages of preparing this body of work, I read a text by the renowned photographic historian Geoffrey Batchen relating to an exhibition he had recently curated called Suspending Time - Life - Photography - Death. The exhibition was presented at the Izu Photo Museum in Shizouka Japan. Unfortunately I did not see the exhibition, hopefully it will travel; my first exposure to his ideas on photography and the problems of time, was in Amelia Grooms review of the exhibition in Frieze magazine issue 133 September 2010. Now as I write in Rome, I open new browser windows and steal these words of his from the IZU Photo Museum’s archive of exhibitions.

'The exhibition is about the capacity of photography to suspend its subjects between life and death, allowing those subjects to defeat the otherwise fatal onset of passing time'.

It is a timely fit for my own thoughts as I finish the works that I am including in Fugitive Mirror : Working with the Marshall Collection, an exhibition in which I have tried to work photographically without a camera and sculpturally without volumetric, heavy materials.

To begin by explaning of the processes involved in making an audio work may seem a strange launching place for a series of exhibition notes accompanying an exhibition consisting of primarily of images, but I am no longer listening to Anhoni and the Johnsons and the headphones hugging my head deliver me the spectral sounds of my most recent collaboration with Melbourne based sound artist J. David Franzke. It is playing on an endless 8 min 42 sec loop.

Earlier this year while I visiting Lewes House in Sussex, (formerly the shared home of John Marshall and his partner Edward Perry Warren - now the offices of the Lewes District Council); Ann Spike kindly photocopied for me four sheets of a handwritten musical score with a line of barely legible text written across the top of the first sheet Waltz by E.P.W. Written out at the Villa Bouonivissi. Sept 1924.

I returned with it to Melbourne, where John Daley, a close friend of mine, rehearsed the piece. I recorded him playing it at his home.We had lengthy discussions about the seemingly inconsistent harmonic errors written into the score, about Warren’s musical competence (evidenced by the musical complexity of the piece) and the its uncharacteristic harmonic hiccups. We decided that someone other than Warren had transcribed the music onto these sheets of paper, and that this layering provided a space of multiple unfolding interpretations. We recorded the ‘original’, as well as the ‘original amendments' and all movement notations that we could decipher. We also recorded what Daley thought Warren had meant musically.

At the same time that I was given the copies of the score I was also given a copy of two photographic portraits of John Marshall, showing him at work in his study with his pet crow sitting on his shoulder. Marshall’s pet crow reputedly flew freely about their home in Rome.

These two unanticipated research outcomes point toward the shared life between the two men and led directly to the first two of the three audio elements used in the composition of the audio piece presented in the exhibition. As Marshall and Warren’s life work was principally as collectors, dealers, and agents of antique sculpture, I selected a third audio element for Franzke and I to work with; the sound of chisels on stone. This assembly of sampled sounds, this small archiving of related sounds, took place in Melbourne.

Adjoining the gallery where the main body of the exhibition is presented is a small circular room. Its painted brickwork reveals the intent of its designer Edwin Lutyens for it to be an exterior space. It is now an interior space with clues that evidence Lutyens original desire for it to function as an exterior stair well that would deliver a climber directly into the BSR library, now the BSR Library and Archive. I spent a day in this small space [not quite large enough for me to stretch out in], making drawings with three kinds of marks. The marks indexed the audio samples waiting patiently in Melbourne. These drawings were then posted to Australia where Franzke pinned them to his studio wall, scoring to them the piece that is now played in the strange little stairwell.

Oliver Wendell Holmes described photography in its early days as ‘the mirror with a memory”. These two words ricochet off each other, launching a multitude of perceptual constellations. Mirrors are most commonly silvered glass, not real silver of course but visually or optically silver; purists of the periodic table will correct me. Actions can be mirrored, as can desires, reflected not only between individuals, but also between our individual frameworks of understanding. Memory presents another terrain of infinite possibility. From the theory of cellular memory, often best explained by the example of the unconscious hand movements of a pianist re-playing of a long-rehearsed piece; to the uncertain possibility of precognition; and of course, the domain of the nostalgic. The latter is something I have tried to develop strategies against in developing this body of work.

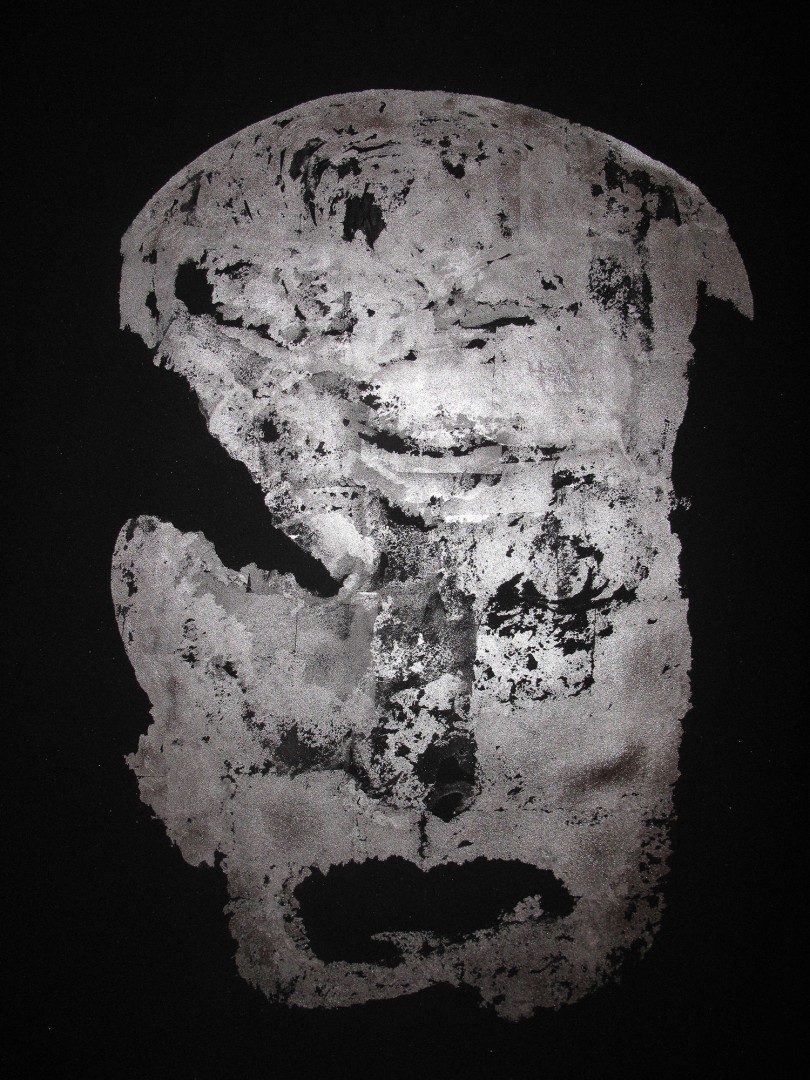

A series of silver and aluminium foil works on sandpaper represent the largest component of the methodologically diverse body of work. Here faces of antiquity merge with faces remembered from journeys on the Metro. A blending of parallel time frames. I don’t take photographs of the living faces that I find myself staring at for perhaps just a little too long in Rome’s increasingly homophobic public spaces. I don’t draw them either; rather I try to commit their detail to memory so I can later merge them with the 19th- century documentary images of ancient lives lived. Shimmering spectral forms emerge, hovering confidently on the infinitely black, delicately dimensional surface that supports an uncertain space between photography, painting, drawing and sculpture. These works reference Pliny’s writings in Natural History, book 33, on the ancient practice of gilding sculpture.

Roman portraits are essentially studies of character and to use a 20th – century art terminology, they are also found objects, archaeologists find all sorts of material.

Combining the visual language of contemporary museology with the often-overlooked visual language of the workshop, two steel, dimensionally modified ‘cavaletti’ or saw-horses, support a glowing light table which is then covered by a large shallow glass case.

In the space between the glowing, sand etched glass and the upper 8mm U.V protection glass; there is a 2 cm breathing space. Into this space I have placed my selection of the original glass negatives. Between these pieces of old glass, I have placed the thinly sliced, richly coloured pieces of natural agate. The process of slicing through the agates reveals images captive within the natural stone. The combining of the rectilinear old glass negatives with the organically shaped, stone slices sets up a formal dialectic, while the images held by each, draw out interesting relationships between the naturally occurring images and the human figures sculpted from stone.

I have selected three groups of negatives, they will be changed over the course of the exhibition, each selection takes a different curatorial position. One depicts the plaster castings of details of the human form, specifically faces. These are essentially images of body parts. Mouths, eyes, noses, etc. They refer not only to the early, quasi forensic processes used in attempts to identify an object’s authenticity; but also in a more contemporary vein, lead us to consider the practise of facial reconstruction for victims of accident or crime, as well as the elective procedures of cosmetic surgery and the changing ideals of beauty. Another selection includes images of sculpture taken in Marshall and Warren’s domestic environment. In these images, it is what can often be glimpsed in the background, or what the object is propped up on that gives us an insight into the personal lives of these men and their idiosyncratic collector culture. The third selection of images refers to the photographic processes undertaken in the assembly of the dossiers that were sent to the acquisition boards of collecting institutions.

On three small shelves attached to the wall, are three small boxes. They occupy a visual space somewhere between the seductive designer shop windows along today’s Via Condotti [very near to where Marshall lived in Rome] and the acid free cardboard storage boxes found in archives all over the world. Each box contains a carbon pigment print, of a digitised 19th-century negative. These are not the expected positive images we are used to seeing from negatives. Rather they are prints that remain in negative; anyone familiar with Photoshop might mistake them as solarised positive images. Each of the images depicts headless life size human figures. One is a draped male figure seated, he seems to be enjoying a moment in a garden, Another is a naked standing female holding out what appears to be a pair of pigtails, a striking image as there is no head for the hair to attach itself to, and the third is a well-dressed roman standing behind a wire fence in what appears to be an over-grown, dilapidated Terrain Vague. Through a playful process of collage, I have replaced their lost or stolen heads with pieces of sliced agate. This time employing a playful reference to the relationships drawn out between the stones and negatives on the light table.

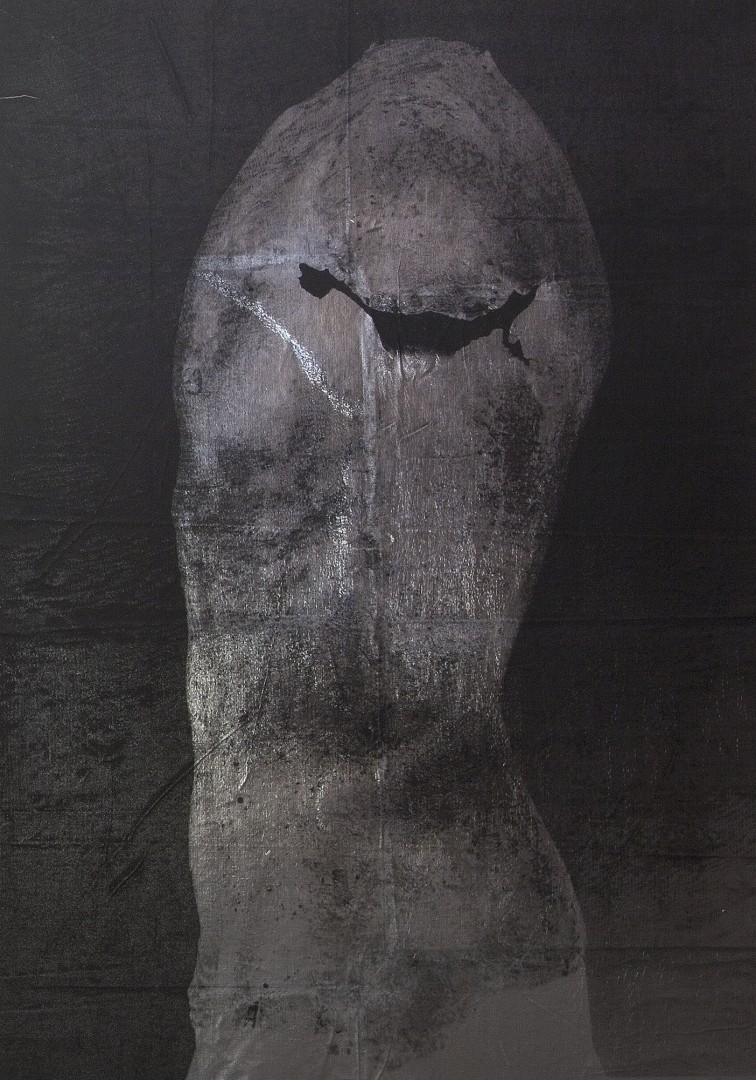

The final visual component of the exhibition is a series of four large screen prints, printed onto silvered linen and black sandpaper. Two images are each printed onto the two different surfaces. They are sourced directly form the archival material. In one we see the exquisitely modelled hair on the back of a young man’s head, we look down his neck to the very top of his shoulders. The original object is a bronze, a Greek bronze, but the image I have worked with is a re-photographed, photographic print of a plaster casting of the original bronze. Even before I came to work with the image, it had a layered story to tell. There are marks in the original bronze that have been transferred with incredible detail to the plaster cast. Then over time, the glass negative itself has come to be marked and my process of screen-printing onto silvered linen introduces another layer of mark making.

I have always imagined that the original object was scaled at 1:1, in lived human proportion, but I have decided to increase the scale in an attempt to monumentalise not the object, but the sense of intimacy, the vulnerability inherent in the loose hair and curve of the back of the neck.

If stone and metal are considered materials of authority and sculpture an art form that is aligned to the notion of the importance of the ‘original’, an interesting thing happens when photography, and screen-printing come into play as both are essentially tied to the idea of reproduction. Each of these screen-printed images avoid the full frontal, the perspective we most commonly used for identifying an individual identity. The second screen-printed work is a side view of another ‘life sized’ bronze male torso; it comes complete with a tear in the metal where we imagine an arm adjoined. It is an abstract, yet familiar form, that hovers in both infinitely dark and blindingly white fields. Separated from any background image, it seems to stand confidently outside of any immediately understood reassuring context; perhaps it is our familiarity with the form that generates a timeless internalised bodily understanding within us.

Contemplating layers of time and experience is a complex business. It seems easier, perhaps even natural, to consider each layer separately. But if we are able to consider the relationship between the perpetually created and the perpetually lost, as in some way similar to our unconscious creation of our own skin, the whole business may just become simpler.

Returning to the question posed at the beginning of these notes. Where do we die together? Perhaps we die together in the space that is insistently cleaved by the avoidable everyday separation of the past and the present.

Andrew Hazewinkel

Rome 2010

I would like to acknowledge the generous assistance with and participation in the project by, Prof. Christopher Smith, Dr. Susan Russell, Valerie Scott, Alessandra Giovenco, Jacopo Benci, and the staff at the British School at Rome. J. David Franzke, John Daley, Rebecca Coates, Stewart Russell, Callum Morton, Ronnie van Hout, Nicholas Mangan, Richard Giblett and Richard Gasper. Dr. Peter Fane-Saunders, Dr. Roberto Cobianci, Dr. Susan Walker at the Ashmolean Museum, Dr. Paul Roberts at the British Museum, Ann Spike at the Lewes District Council, Pier Angelo Petreri, Gabriele di Tanna, Andrea Amato, Heidi Specker, Brent Harris, and Stefania Manna. I would also like to thank the panel members of International Projects at Arts Victoria who have generously supported this project.

VIVIAMO INSIEME IN UNA FOTOGRAFIA DEL TEMPO

Anhoni and the Johnsons (un pugno d'amore)

L'esibizione nota, Andrew Hazewinkel- Translated by Stefania Manna

Se Anhoni ha ragione, questo verso della canzone “Un pugno d’amore” pone una domanda, dove moriamo insieme? Roland Barthes suggerisce che la “catastrofe” della nostra morte, l’ineluttabile coscienza della nostra morte, è dentro ogni fotografia.

Non ne sono certo, ma se ci concentriamo su immagini della forma umana, o su immagini di immagini della forma umana, Bathes ha ragione. Questo è ciò che ho fatto negli ultimi quattro anni, a partire dal 2006 con il mio primo approccio al mondo climaticamente controllato del Foto Archivio della British School a Roma, incontrando per la prima volta John Marshall, che visse tra il 1862 ed il 1928.

L’importante ma non molto nota collezione Marshall consiste in oltre 2700 stampe fotografiche alla gelatina d’argento e 630 lastre di vetro, che documentano la scultura greca e romana, databili tra la fine del ‘900 e l’ inizio dello scorso secolo.

Amo il vetro; è un materiale assolutamente contemporaneo, una sostanza curiosa che per definizione è un solido amorfo. Racchiude in involucri trasparenti le città che abitiamo, riflette il nostro volto al mattino quando facciamo la barba o ci trucchiamo. Ci aiuta ogni giorno a capire se siamo pronti o no per affrontare la giornata. Ha anche un passato antico, che risale ad origini mesopotamiche, intorno al 3500 a.C.. Ha una stretta relazione con il mondo senza tempo della scienza ottica e, per associazione, con la creazione di immagini.

Se la storia del ritratto fotografico è considerata come una serie di tentativi di immortalare la morte, che succede quando un fotografo si concentra su soggetti non animati con la sensibilità normalmente dedicata a soggetti animati e rappresenta il ritratto di un ritratto? Siamo due volte lontani dall’essenza del soggetto originale, siamo improvvisamente nel vortice del cane che si morde la coda? O siamo sospesi nello spazio ricercato tra la vita e la morte?

John Marshall era l’unico agente europeo del Metropolitan Musuem of Art di New York tra il 1905 e il 1928, con un ruolo centrale nelle acquisizioni per le collezioni greche e romane. Precedentemente, tra il 1894 e il 1904, lui e il suo compagno Edward Perry Warren erano stati responsabili delle collezioni greche e romane del Boston Museum of Fine Arts, la principale collezione del tempo in America.

Lavorando a Roma, Marshall diede incarico a fotografi italiani (spesso si tratta di Cesare Farraglia) di riprodurre immagini di antichità messe sul mercato. Con queste immagini preparava dossier completi da sottoporre ai comitati del MET, del BMFA e di altre importante istituzioni museali. Le immagini fotografate sono di straordinaria bellezza e possono considerarsi esse stesse opere d’arte. Queste prime immagini fotografiche documentano una enorme varietà di oggetti: terracotte, marmi, bronzi, come anche artigianato in avorio, osso e argento. Molti di questi oggetti sono considerati oggi capolavori dell’antichità, alcuni sono ritenuti falsi eccellenti.

Mi piace rubare cose. Mentre stavo preparando l’ultima fase di questo lavoro, mi sono imbattuto in un testo del famoso storico della fotografia Geoffrey Batchen su una mostra da lui curata di recente dal titolo Suspending Time- Life-Photography-Death . La mostra è stata presenta all’Izu Photo Museum di Shizouka in Giappone.

Sfortunatamente non ho visto la mostra, speriamo possa viaggiare; il mio primo approccio a questa idea della fotografia in relazione ai problemi del tempo è stato attraverso un articolo su quella mostra di Amelia Grooms sulla rivista Frieze n. 133, Settembre 2010. Dato che scrivo da Roma, apro finestre di esplorazione e rubo questa sua citazione dall’archivio delle mostre dell’Izu Photo Museum.

La mostra ha per tema le capacità della fotografia di sospendere i suoi soggetti tra la vita e la morte, permettendo a questi soggetti di sconfiggere l’assalto altrimenti fatale dello scorrere del tempo.

Perfettamente in tempo con i miei stessi pensieri nel momento conclusivo delle opere in questa mostra Fugitive Mirror, nelle quali ho sperimentato un lavoro fotografico senza una fotocamera e un lavoro scultoreo senza pesanti volumi di materia.

Iniziare con una spiegazione dei processi attraverso i quali si produce un audio può sembrare alquanto inusuale per una serie di pensieri che accompagnano una mostra consistente principalmente in immagini.

Ma non mi riferisco all’ascolto di Anthony and the Johnsons e le cuffie che ho in testa mi regalano il suono del mio ultimo lavoro audio, fatto in collaborazione con l’artista del suono J. David Franzke che lavora a Melbourne; si tratta di un loop senza fine lungo 8 minuti e 42 secondi.

All’inizio di quest’anno ho visitato la Lewes House nel Sussex, in passato la casa di John Marshall e del suo compagno Edward Perry Warren ed oggi gli uffici del Consiglio del Distretto di Lewes; in quell’occasione Ann Spike mi ha gentilmente fotocopiato quattro fogli di uno spartito manoscritto con un testo quasi illeggibile in alto sul primo foglio: “Waltz by E.P.W. Written out at the Villa Bouonivissi. Sept 1924”.

Sono tornato a Melbourne dove John Daley, il compagno di un mio caro amico, ha suonato quel pezzo musicale permettendomi di registrarlo a casa sua.Abbiamo avuto lunghe conversazioni sugli errori armonici di partitura apparentemente incoerenti; sulla competenza musicale di Warren, evidente dalla complessità del pezzo e dalla anomala armonia a singhiozzo.Siamo giunti alle conclusioni che qualcun altro avesse trascritto la musica sullo spartito e che questa stesura aveva delineato uno spazio per la manifestazione di interpretazioni multiple.Abbiamo registrato il pezzo “originale” e quello “originale corretto” e tutte le annotazioni di movimento che potevamo decifrare. Abbiamo registrato inoltre ciò che Daley pensava Warren volesse intendere musicalmente.

Contestualmente alla copia dello spartito, mi furono date copie di due ritratti fotografici di John Marshall (il boyfriend di Warren in gergo odierno) che lo mostrano a lavoro nel suo studio con il suo piccolo corvo seduto comodamente sulla spalla. E’ risaputo che il corvo di Marshall volò via dalla sua casa romana.

Questi due imprevedibili risultati della ricerca puntano alla vita condivisa da questi due uomini e sono diventati i prime due dei tre elementi audio impiegati nella composizione sonora presentata in Fugitive Mirror. Dato che l’attività principale di Marshall e Warren era quella di collezionisti, commercianti ed agenti di antiche sculture, ho selezionato un terzo elemento: il suono dello scalpello sulla pietra. La composizione dei suoni, questo breve risultato sonoro, è stata fatta a Melbourne.

Adiacente alla galleria con la parte principale delle opere, c’è una piccola sala circolare. La sua decorazione di mattoni dipinti rivela il proposito del suo autore Edwin Lutyens di farne uno spazio esterno. Si tratta oggi di uno spazio interno, che nelle intenzioni di Lutyens sarebbe dovuto essere una scala circolare esterna per salire direttamente dentro la biblioteca della BSR, oggi biblioteca e archivio. In questo piccolo spazio, così piccolo che io non riesco a stirarmici dentro, ho trascorso un giorno intero, facendo disegni con tre tipi di pennarelli, uno per ciascuno dei pezzi audio che stavano aspettando pazientemente a Melbourne. Questi disegni sono stati quindi spediti in Australia dove Franzke li ha appesi nel suo studio e ha scritto il pezzo musicale che viene suonato in questo piccolo strano “corpo” scala.

Oliver Wendell Holmes ha descritto la fotografia agli albori come “lo specchio con una memoria”. Queste due parole rimbalzano una sull’altra, generando una moltitudine di costellazioni perpetue. Gli specchi sono comunemente vetro argentato, non argento vero naturalmente ma argento all’apparenza, i puristi della tavola periodica mi correggerebbero immagino.

Le azioni, come i desideri, possono essere specchiate, riflesse non solo tra un certo numero di individui ma anche tra (e) le nostre strutture di comprensione individuali. La memoria presenta un altro terreno di possibilità infinite, dalle teorie della memoria cellulare, spesso meglio descritta con l’esempio della sonata incosciente di un pezzo che è stato a lungo provato e riprovato dal pianista. C’è una possibilità incerta di precognizione; e ovviamente si trova nel dominio della nostalgia. Quest’ultima è qualcosa contro la quale ho tentato di sviluppare strategie con l’esperienza di questo lavoro.

Una serie di opere con fogli in argento ed alluminio su carta vetrata rappresentano la più ampia componente di un corpo di opere metodologicamente diverse. Qui volti dell’antichità si fondono con visi che ricordavo dai miei viaggi nella Metro. Una curvatura di strutture temporali parallele. Non fotografo volti viventi che mi sorprendo a fissare per le strade; strade che a Roma sono diventate progressivamente omofobiche. Non li disegno neanche; piuttosto tento di impararli a memoria così da poterli mischiare con le immagini di antiche vite vissute documentate nell’800. Vengono fuori tremolanti forme spettrali, che galleggiano sicure di sé sulla superficie infinitamente nera, delicatamente dimensionata, che rappresenta uno spazio incerto tra fotografia, pittura, disegno e scultura. Questi lavori si riferiscono agli scritti (pregevoli) di Plinio nella Storia della Natura, libro 33, dove si parla dell’antica pratica della scultura dorata.

I ritratti romani sono essenzialmente studi di stile e, per usare un termine di arte contemporanea, sono anche oggetti trovati; gli archeologi trovano ogni sorta di cose.

Combinando il linguaggio visivo della museologia contemporanea con il consueto panorama dell’officina, due “cavalletti” d’acciaio, dimensionalmente modificati, o cavalletti per segare la legna, supportano un tavolo illuminato coperto da un’ampia bassa scatola in vetro.

Nello spazio tra l’illuminazione, il vetro satinato e il vetro superiore da 8mm di protezione, ci sono 2 cm di aria. Tra questi pezzi di vecchio vetro, ho posizionato lastre sottili di agata naturale riccamente colorata. Il procedimento di ridurre l’agata in lastre sottili rivela immagini prigioniere nella pietra naturale. La combinazione dei vecchi negativi in vetro rettangolari con le sottili lastre in pietra di forma organica stabiliscono una dialettica formale; mentre le immagini, ciascuna per sé, tracciano una relazione interessante tra le forme disegnate dalla natura e le figure umane scolpite nella pietra.

Ho selezionato tre gruppi di negativi, che verranno cambiati nel corso della mostra cosicché ogni installazione avrà un taglio curatoriale diverso. Una selezione comprende immagini che mostrano calchi di gesso di dettagli della forma umana, essenzialmente volti. Bocche, occhi, nasi, etc. Essi fanno riferimento non solo al primo processo, quasi da medicina legale, che si usa per l’autenticazione di un oggetto, ma anche, in chiave più contemporanea, a qualcosa che ci riconduce a considerare la pratica della ricostruzione facciale per le vittime di crimini o incidenti, come anche alle procedure elettive della chirurgia estetica e del cambiamento dei canoni della bellezza.

Un’altra selezione comprende immagini di sculture fatte nell’ambiente domestico di Marshall e Warren. In queste immagini, è ciò che si intravede sullo sfondo o ciò contro cui è poggiato l’oggetto a dare un’idea della vita personale di questi due uomini e della loro idioscratica cultura da collezionisti. La terza selezione di immagini si riferisce ai processi fotografici adottati per l’assemblaggio dei dossier per i comitati di acquisizione delle istituzioni museali.

Su tre piccole mensole attaccate al muro, ci sono tre piccole scatole. Esse occupano uno spazio visivo in qualche modo tra le seducenti vetrine disegnate lungo la Via Condotti di oggi (molto vicino al luogo dove Marshall viveva a Roma) e le scatole prive di acido tipiche degli archivi di tutto il mondo. Ogni scatola contiene una stampa con pigmento a carbone, di negativi del XIX sec. Queste non sono le immagini che siamo abituati ad ottenere dai negativi. Sono piuttosto stampe che rimangono negative; se si ha familiarità con Photoshop, si potrebbe scambiarle per immagini solarizzate positive. Ogni immagine ritrae figure umane senza testa a dimensione reale. Una è una figura maschile seduta ornata con drappo, che sembra godersi un momento all’aria aperta. Un’altra è una figura femminile nuda in piedi che stringe qualcosa che sembra essere un paio di trecce, un’immagine stupefacente visto che non c’è la testa alla quale si attaccano i capelli; e la terza è un romano ben vestito in piedi dietro una recinzione, all’interno della quale sembra esserci un accresciuto, decrepito Terrain Vague. Con un processo giocoso di collage, ho sostituito le loro teste perse o rubate con pezzi di lastre di agata. Questa volta implicando un riferimento scherzoso alla relazione tra le pietre ed i negativi sul tavolo illuminato.

La componente visuale finale della mostra è una serie di quattro immagini di grandi dimensioni, stampate su lino argentato o su carta vetrata nera. Due immagini sono stampate ciascuna sulle due diverse superfici e sono state prese direttamente dal materiale d’archivio. In una si vede la capigliatura squisitamente modellata del retro della testa di un giovane uomo, che arriva alla fine del collo, all’attaccatura delle spalle. L’oggetto originale è un bronzo, un bronzo greco, ma l’immagine con cui io ho lavorato è una stampa fotografica rifotografata di un calco in gesso del bronzo originario. Anche prima di cominciare a lavorare con l’immagine, si capisce che racconta essa una storia. Ci sono segni nel bronzo originale, trasferiti con incredibile precisione al calco in gesso. Poi con il tempo, il negativo in vetro stesso ha cominciato a graffiarsi ed il mio procedimento di stampa di lino argentato introduce un altro strato di segni.

Ho sempre immaginato che l’oggetto originale fosse in scala 1:1, a dimensione reale, ma ho deciso di aumentare la scala con l’intensione non di rendere l’oggetto monumentale, ma di restituire il senso di intimità, la vulnerabilità dei capelli persi e la curva della parte retro del collo.

Se la pietra e il metallo sono considerati d’autorità in arte materiali da scultura, da cui deriva la nozione di importanza dell’”originale”, quando intervengono la fotografia e la stampa accade qualcosa di interessante, dato che sono entrambe legate all’idea della riproduzione.

Ciascuna di queste immagini evita la piena visione frontale, la prospettiva che normalmente usiamo per identificare un individuo.

La seconda opera stampata è il profilo latereale di un altro bronzo a dimensione reale, un torso maschile, che presenta una spaccatura del metallo nel punto dove dovrebbe innestarsi il braccio. E’ una forma astratta, ma comunque familiare, che si aggira in un campo infinitamente nero ed uno ciecamente bianco. Separati da qualsiasi immagine di sfondo, sembrano erigersi con confidenza al di là di ogni rassicurante contesto immediatamente comprensibile; forse è la familiarità con la forma che genera una nostra comprensione corporea interiorizzata senza tempo.

La contemplazione della stratificazione del tempo e dell’esperienza è operazione complessa. Sembra più facile, forse anche più naturale, analizzare ogni strato separatamente. Ma se riusciamo a considerare la relazione tra ciò che viene eternamente creato e ciò che viene eternamente perduto, come la generazione della nostra pelle rende nascosto ma evidente in superficie ciò che definisce, l’intera questione potrebbe divenire più semplice.

Tornando alla prima domanda posta in questo testo. Dove moriamo insieme? Forse moriamo insieme nello spazio iper-insistentemente spaccato, in modo apparentemente inevitabile, dalla separazione quotidiana tra passato e presente.

Andrew Hazewinkel

Roma 2010.

Vorrei ringraziare la generosa assistenza e partecipazione al progetto di: Dr Christopher Smith, Dr Susan Russell, Valerie Scott, Alessandra Giovenco, Jacopo Benci e lo staff della British School at Rome. J. David Franzke, John Daley, Rebecca Coates, Stewart Russell, Callum Morton, Ronnie van Hout, Nicholas Mangan Richard Giblett e Richard Gaspar. Dr. Peter Fane-Saunders,Dr Roberto Cobianci, Dr Susan Walker dell’Ashmolean Museum, Dr Paul Roberts dell British Museum. Ann Spike al Lewes District Council, Pier Angelo Petreri, Gabriele di Tanna, Andrea Amato, Heidi Specker, Brent Harris e Stefania Manna. Vorrei inoltre ringraziare i membri dell’International Panel dell’Arts Victoria che hanno generosamente sostenuto questo progetto.